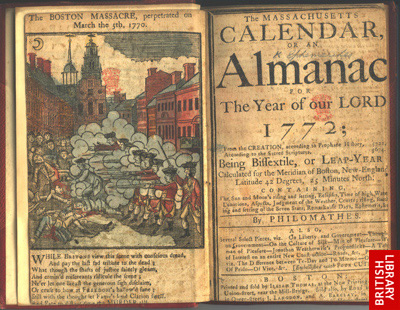

Above: A Copy of Paul Revere's engraving of the Boston Massacre, The Massachusetts Calender, for...1772...By Philomathes [from our 'American revolution' web resource]

[This year the British Library Americas Blog and U.S. Studies Online will be publishing a series of posts as part of the Eccles Centre’s Summer Scholars 2015 series of talks. The articles are based on talks given by a range of writers and scholars conducting research at the British Library thanks to generous research fellowships and grants awarded by the Eccles Centre. This first post it by Sally E. Hadden, Western Michigan University, on part of her research into lawyers living in 18th century Boston. A schedule for the remaining Scholars talks can be found here]

For my current book project, I’m investigating lawyers who lived in 18th century Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston. Towards the end of the century, these individuals took a leading role in conducting the American Revolution, and also in the creation of the legal structures that became new state governments and the national government of the United States. As lawyers, they were also a bit of a closed community, speaking an arcane language filled with terms that others could not understand unless they shared the same training: words like fee tail male, executrix, intestacy, writs of attachment, or tripartite bonds were their stock in trade, plus Latin tags for every occasion. Being part of this community of men trained in the same field held them apart from all others, as well as holding them together in a sort of invisible association.

This invisible association of men traveled together for weeks at a time, four times per year. Colonial lawyers who wanted to earn their livings could not stay in their offices and expect clients to always find them—they needed to travel on circuit, going from town to town as the judges did, visiting the far-flung parts of a county to bring justice with them. Imagine this cluster of men, traveling as they did on horseback for a grimy day or two, then setting up camp in the taverns and inns of a new place. It was a sort of traveling circus, and within the circus, the men who were judges and lawyers formed a tight-knit group, with friendships formed there that often lasted a lifetime. Even after the Revolution, John Adams still spoke with fondness about Jonathan Sewall, a man he shared a bed with while traveling on circuit, his friend of many years—who became a loyalist.

It was the friendships within this group that first drew my attention to loyalist lawyers. I began to turn up the names of individuals who had been part of this tight-knit invisible association, but whose politics led them to part from their friends, their profession (as they knew it), and take refuge during the American Revolution. As part of the exodus of (we estimate) over 50,000 individuals from the colonies, these men have sometimes been lumped in and studied with other loyalists—but they were a breed apart. Unlike the shoemaker or blacksmith, they could not readily find work in just any old town: they needed one with a courthouse, and enough people, to sustain their legal practices.

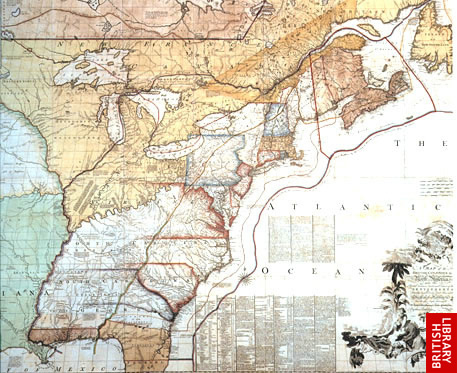

Above: drawing lines after the war, Mitchell The Red Lined Map, 1775, K.Top [from our 'American Revolution' web resource]

My work at the British Library involves tracking Boston men like Andrew Cazneau, Samuel Fitch, Benjamin Gridley, James Putnam, Ward Chipman, Daniel Leonard, Rufus Chandler, Abel Willard, Daniel Bliss, and even law student Jeremiah Dummer Rogers. Of the 47 lawyers working in Boston at the time of the Revolution, they split roughly down the middle in terms of their choices: about 20 stayed and took up the patriot cause, while about 20 left with the British and went overseas seeking to remain loyal. From Philadelphia, the sons of Chief Justice William Allen in Philadelphia, Andrew and James, trained in the law and wanted to continue practicing, but not under the new American regime. James Allen wrote in his diary June 6, 1777 that the laws of Pennsylvania were disregarded, the assembly was ridiculous, and the courts were not open. All of this made “a mockery of Justice.” He and others in his family took refuge with the British, and then eventually left America for good. Still, it was a smaller number of loyalist lawyers who left Philadelphia than in Boston. And in Charleston, the number of departing men was smaller still. Only eight or nine of the most prominent lawyers of the city chose to depart, most of whom were middle-aged, and inclined to conservatism, like their fellow loyalists. James Simpson, the attorney general, William Burroughs, the head of chancery, and Egerton Leigh all had large practices and departed, Charles Pinckney took protection under the British while they occupied Charleston—but the remainder of the men with the most numerous clients remained behind as patriots. One big question my study will eventually address is, why did so many more Boston lawyers leave for England than men in those same professions in Philadelphia or Charleston?

These men fled to a variety of destinations, including modern-day Canada, the Caribbean, and France. Most went to London. Clubs sprang up to provide these London exiles with conversation, a network of information, and recreation. By the summer of 1776, they had formed the “Brompton-Row Tory Club” or “Loyalist Club” which met for dinner, conversation, and backgammon on a weekly basis, in homes that lined the current day Brompton Road. They made claims to the Parliament loyalist commission, seeking compensation for their lost homes, libraries, and incomes. Thomas Hutchinson, whose diary and correspondence from this period are housed in the manuscript collections of the British Library, provides insight into the changing prospects of these men. Many of them had less and less hope that their former lives would be restored, as the war dragged on. They moved out of London for less expensive towns like Bristol, Sidmouth, Exeter, Bath, even South Wales.

A very few, like Daniel Leonard, chose to take up the practice of law again in London, though for Leonard it required undergoing the various meals and moots associated with student life at the advanced age of 37 to join the Middle Temple before he could do so. Most colonial lawyers—aside from those in Charleston—had not completed their legal training in London. Leonard became a barrister and in 1781 was appointed Chief Justice of Bermuda, where he lived for several years, prior to retirement and death in London.

Recapturing what happened to these men as they scattered to smaller cities, or spread out to other parts of the British Empire, forms an important part of my larger project. The riches at the British Library will undoubtedly reveal more about their choices, once the Revolution had turned in favour of the Americans in 1778.

[SH. More on Summer Scholars here]