'It is not in the nature of an Irishman to fight with four or five pounds of boiled pork and biscuit banging at his hip' – so beings the third and final part of the short, thirteen page account of The Last Days of the 69th in Virginia: A Narrative in the Three Parts (General Reference Collection 9604.aaa.10.), written by then-Captain Thomas Francis Meagher in 1861 during the early days of the American Civil War. It is one of a number of archive holdings the British Library has relating to the conflict and the involvement of Irish American men and women in the fight for the survival of a United States between 1861-1865, an area which forms the foundation of my doctoral research, with the generous fellowship support of the Eccles Centre for American Studies.

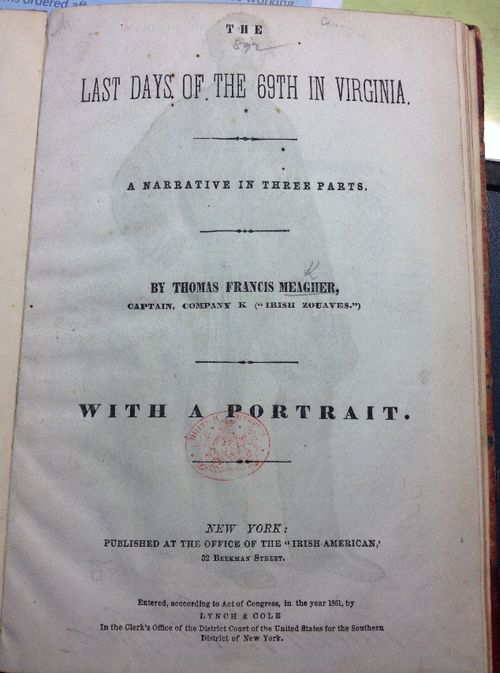

Thomas Francis Meagher, The Last Days of the 69th in Virginia: A Narrative in Three Parts (New York, 1861), title page. Image in the public domain.

Meagher, a former Young Irelander who had escaped exile in Van Diemen’s Land and migrated to America in the early 1850s, was one of the most prominent Irish-born soldiers during the war. He rose from a captain attached to the 69th New York State Infantry Regiment to founder and commanding general of the Irish Brigade, the bastion of Irish American military service, with its constituent regiments present at every major battle of the brutal conflict. The 69th New York formed the Brigade’s foundation. They were born from a state militia regiment whose pre-war fame originated after the refusal of their commander Colonel Michael Corcoran (also Irish-born and later himself a prominent Union general) to march the past Edward, Prince of Wales during the future king’s visit to New York City in 1860. The exploits of Meagher, Corcoran, the 69th New York and the Irish Brigade’s military service during the Civil War were widely known in contemporary Union and Confederate societies and were recounted in several of the memoirs, accounts, newspaper records and ballads. Some of the songs relating to the Irish experience of the conflict can be seen in the Library’s online gallery collection of digitized American Civil War archives.

Meagher’s Last Days of the 69th in Virginia details events the 69th New York Infantry participated in from 12-18 July 1861 – the days leading up to the First Battle of Bull Run at Manassas, Virginia, the first major battle of the Civil War. It thus gives a fascinating and unique insight into the mobilisation and immediate experiences of thousands of soldiers rallying to the impending front-line, completely unaware of the battle and the subsequent four long tortuous years of war that would soon be upon them. Meagher chose to focus on the days preceding the battle fought on 21st July because its “incidents and events, the world, by this time, has heard enough… the battle, the [Union] retreat, the alarm and confusion of the Federal troops, columns and volumes have been filled”. Instead, Meagher’s writing reveals the journey of the 69th New York from their base at Fort Corcoran on Arlington Heights outside of Washington D.C., to the fields around Manassas, travelling through the Virginian town of Centreville, made famous in a wartime photograph taken by Timothy H. O’Sullivan showing its use as a Confederate supply depot and war’s scarring on the land. The image was published in Alexander Gardener’s collection of Civil War photography, of which the Library holds a copy (General Reference Collection 1784.a.13.). Meagher was not particularly complementary about Centreville, describing is as a 'dingy, aged little village' with a 'miserable little handful of houses. It is the coldest picture conceivable of municipal smallness and decrepitude…One is astounded on entering it, to find that a molehill has been magnified into a mountain.'

Captain Thomas Francis Meagher, later General Meagher, commander of the Union Army’s Irish Brigade (1861).

Someone else turned into a mountain in Civil War histories is 'our Brigadier, Colonel Sherman, a rude and envenomed martinet' who, for 'whatever his reasons for it were…exhibited the sourest malignity towards the 69th'. Meagher spoke here of William Tecumseh Sherman, more famous as the general who led the Union advance through the southern states in the final years of the Civil War. A colonel at the First Battle of Bull Run, Sherman’s continual ordering of the Irish soldiers to bivouac on “the dampest and rankest” of ground led Meagher to state that the then-colonel 'was hated by the regiment'. Despite no love being lost between Meagher and Sherman, the former unwittingly included a rather pointed note of historical irony about the latter. He described how advancing Union soldiers passing by farmsteads on the road to Manassas were 'forbade' to touch the 'cocks of hay and stacks of corn'. The people of Georgia would have surely wished that this version of Sherman had marched through their state in 1864.

Alongside derogatory descriptions of southern towns and fellow Union Army officers, Meagher detailed the exhausting march and Confederate skirmishes through the Virginian countryside in the July heat. Bivouacking subjected the men to night-time humidity, which caused the Stars and Stripes to become 'damp with the heavy night dews'. In the day the men of the 69th New York dealt with 'heat and dust and thirst'. His account paints a sensory portrait of the Union Army mustering to face the Confederacy; a visual 'splendid panorama, those four miles of armed men – the sun multiplying, it seemed to me, the lines of flashing steel, bringing out plume and epaulette and sword, and all the finery of war, into a keener radiance, and heightening the vision of that vast throng with all its glory'. He spoke similarly about aural imagery: 'the jingling of the bayonets, as the stacked muskets tumbled one after another… The sound was so like that of sabres slapping against the heels and spurs of charging troopers'. Amongst those on the march was the 79th New York Infantry Regiment looking 'stanch and splendid'. Led by Colonel James Cameron, the regiment were nicknamed 'The Highlanders' in honour of their connection to New York Scottish fraternity organisations.

The Library’s copy of The Last Days of the 69th in Virginia was 'published at the office of the '"Irish-American"' in New York City by Lynch and Cole, publishers of the Irish-American newspaper, the foremost Irish organ for the largest community of Irish men and women in America. It was subsequently circulated in other Irish newspapers in the country, namely the Boston Pilot. The account is in three parts, leading to the suggestion the publishers serialised Meagher’s writings before producing a book form sometime in the last summer/early autumn of 1861. It is possible that it was used as part of Meagher’s promotion tour of Irish American communities in New York, Boston and Philadelphia while he was galvanising support for the formation of the Irish Brigade. Very few copies of the account in this book form exists today and although it appears in the bibliographies of Irish American, wartime and Meagher histories, it is rarely quoted from, with scholars choosing newspaper accounts of his numerous wartime speeches and Michael Cavanagh’s Memoirs of General Thomas Francis Meagher (General Reference Collection 10882.g.1.) as their primary source focus. With limited personal wartime writings of Thomas Francis Meagher available, The Last Days of the 69th in Virginia provides a revealing insight into one prominent Irish American’s contemporary account of the initial days of the American Civil War. It helps show how the Irishman’s gift of rhetorical skill transposed itself to his writing, despite his friend Captain W.F. Lyons stating in his book Brigadier-General Thomas Francis Meagher (General Reference Collection 10882.aaa.29.) that 'journalism was, in fact, not Meagher’s best field of action…[which] he had abandoned…for the stormy life of the soldier'.

What The Last Days of the 69th in Virginia demonstrates is that Meagher’s writing of the actual field of action was extremely eloquent. He could switch from the humorous – describing how Corcoran’s horse 'was greedily eating newspapers' on the morning of the First Battle of Bull Run – to the patriotic fervour that became commonplace amongst lyrical expressions of Irish American dual identity in the nineteenth century. He also provides a perfect description of why such a source is important for American Civil War scholars. Meagher’s account created 'a picture far more striking and exciting than any I had ever seen. War, assuredly, has its fascinations as well as its horrors…and so emboldens and spurs the tamest into heroism.'

– Catherine Bateson