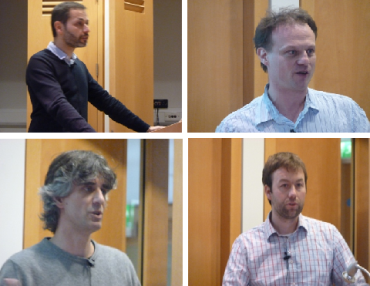

Clockwise from top left: Luis Carrasqueiro, Peter Robinson, Johan Oomen, Roeland Ordelman

We know that once we've have an object in digital form then the opportunities for analysing it, visualising it, sharing it, mashing it, deconstructing it, rebuilding it, and learning from it are great. We know that through its very structure it can be linked up with other kinds of digital objects, and that the way digital objects can be networked together is changing scholarship and research. But some digital objects are easier to work with than others.

Take speech recordings for instance. The extent of record speech archives - either audio or video - is probably of a number beyond calculating, but they play only a reduced part in the online search experience. Type in a search term into whatever, and you will bring up textual records, images, maps, videos and more, but you won't have searched across a whole vast tier of digital content, which is the speech content embedded in audio and video records. You will have searched across associated descriptions, but not the words themselves. You are not getting the whole picture, and this leads to bias in what you find, what you may use, and what conclusions you come to in your research.

Coming to the rescue - just possibly - are speech-to-text technologies. In a nutshell these are technologies which use processes analogous to Optical Character Recognition (OCR) to convert speech audio into word-searchable text. The results aren't perfect transcriptions, with accuracy rates ranging from 30-90% depending on the kind of speech and the familiarity of the software with the speaker. Smartphones now come with a speech-to-text capability, because recognising the commands from a single, familiar voice is now relatively easy for our portable devices. Scaling this up to large archives of speech-based audio and video is rather more of a challenge.

The British Library has been looking at this issue over the past year through its Opening up Speech Archives project, funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council. The aim of the project is not to identitfy the best systems out there - you quickly learn that it's not a case of what's best but rather what is most suitable for particular uses - and not about implementing any such system here (yet). Instead we've been looking at how speech-to-text will affect the research experience, and trying to learn from researchers how they can work with audiovisual media opened up through such tools - and how their needs can be fed back to developers.

One output of the research project was a conference, entitled Opening up Speech Archives, which was held at the Library on 8 February 2013. This event bought together product developers, service providers, archivists, curators, librarians, technicians and ordinary researchers from a variety of disciplines. We also had demonstrations of various systems and solutions for delegates to try out.

The conference room awaits

For the record, here's who spoke and what they had to say:

Luke McKernan (that's me) spoke on 'The needs of academic researchers using

speech-to-text systems'. You can read my blog post on which this was based, or download a copy of my talk, which tried to look at the bigger picture, arguing that speech-to-text technologies will bring about a huge change in how we discover things.

John Coleman (Oxford University) spoke on 'Using speech recognition, transcription

standards and media fragments protocols in large-scale spoken audio collections'. Find out more about his work on the British National Corpus (100 million word collection of samples of written and spoken language from a wide range of sources, designed to represent a wide cross-section of current British English) and the Mining a Year of Speech project.

Peter Robinson and Sergio Grau Puerto (also Oxford University) discussed 'Podcasting

2.0: the use of automatic speech-to-text technology to increase the

discoverability of open lectures'. Find out more about their JISC-funded SPINDLE project, which used open source speech-to-text software to create keywords for searching the university's podcasts collection.

Johan Oomen, Erwin Verbuggen and Roeland Ordelman

(Netherlands Institute for Sound & Vision) spoke about the hugely impressive (and handsomely-funded) work being funded in the Netherlands to open up audiovisual archives, with individual talks on 'Time-based

media in the context of television broadcast and digital humanities', 'Creating smart

links to contextual information' and 'The

European dimension: EUscreenXL'. You can find their presentation on SlideShare.

Ian Mottashed (Cambridge Imaging Systems) talked about the complementary field of subtitle capture and search in 'Unlocking value in footage with time-based

metadata'. If you are in a Higher Education institution which subscribes to the off-air TV archive Bob National you can see the results of their work - or else come to the BL reading rooms and try out our Broadcast News service, which uses the same underlying software with subtitle searching.

Theo

Jones, Chris Lowis, Pete Warren (BBC R&D) gave us 'The

BBC World Service Archive: how audiences and machines can help you to publish a

large archive'. This was about the BBC World Service Prototype, which is using a mixture of catalogue, machine indexing of speech files (using the open source CMU Sphinx) and crowdsourcing to categorise the digitised World Service radio archive. If you are keen to test this out, you can sign up for the prototype at http://worldservice.prototyping.bbc.co.uk. It could be how all radio archives will operate one day.

Chris Hartley of information reprocessing company Autonomy talked about 'Practical examples of opening up speech (and

video) archives', showing the extraordinary ways in which high-end systems can now analyse text, speech, images, music and video to generate rich data and rich data analyses. The main customers for such systems have been governments and the military - now education is starting to be the beneficiary, with JISC Historic Books using an Autonomy IDOL platform (though with no audio or vidoe content, yet).

Rounding things up was Luís

Carrasqueiro of the British Universities Film & Video Council speaking on 'Widening the use

of audiovisual materials in education', including mention of the BUFVC's forthcoming citation guidelines for AV media, which could play a major part in helping making sound and video integral to the research process. He also gave us the key message for the day, which was "Imperfection is OK - live with it". Wise words - too many considering speech-to-text systems dream of something that will create the word-perfect transcription. They can't, and it doesn't matter. It's more than enough to be able to search across the words that they can find, and to extract from these keywords, location terms, names, dates and more, which can then be linked together with other digital objects. Which is where we came in.

We'll be publishing project papers and associated findings on a British Library web page in due course, and hope to make a demonstration service available in our Reading Rooms soon. Meanwhile, if you want to see some speech-to-text services in action, here are a few to try out:

- ScienceCinema is a collection of word-searchable lecture videos from the U.S. Department of Energy and CERN, indexed using Microsoft's speech-to-text system MAVIS.

- Voxalead is a multimedia news test site, searching across freely-available web news sites from around the world, bringing together programme descriptions, subtitles and speech-to-text transcripts and presenting the results in a variety of interesting ways. It's an off-shoot of French search engine Exalead.

- DemocracyLive is a BBC News site that combines Autonomy-developed speech-to-text with Hansard to provide word-searching of video records of the Houses of Parliament, Select Committees, the national assemblies and more.

Audience, agog