The impact that a thoughtful visualisation has cannot be underestimated. However, it's easy to forget how tremendously useful they are for understanding your own data, before you even know what you have.

The questions "Is there...?" and "What if...?" drive the exploration of data. Often, these questions are best answered by creating something in reply: "This is what it looks like in that context." This can be as simple as creating a chart from a spreadsheet, or pulling out all the key words and phrases and putting them all together on a single page. There are also a number of tools that will take structured data and provide different ways to examine them.

This post will not be a survey of visualisation software, but it will contain a few worked examples of how I approached some data and how I went about exploring it using the occasional visualisation. There is python code below but you won't need to know how to program to understand what it does.

Case Study: A "Random" identifier?

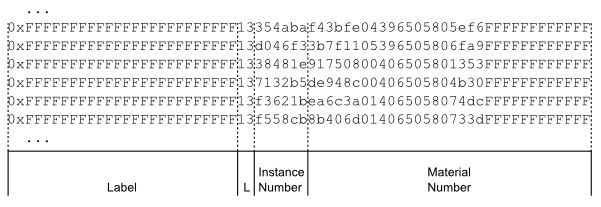

I was given access as part of an exploratory project to a large amount of media 'stuff', for which the only metadata for it is that each item had a long hexadecimal string for an identifier, its Unique Material Identifier, or UMID. The file metadata and folder structure reflected the date at which the item was accessioned into the system, not the date that the item was published, recorded or created. I found an explanation of the UMID's internal structure here [NB: PDF] but, a standard is only as standard as its implementations are and I couldn't be confident that the UMIDs I had fit this structure. However, a random sample of UMIDs - randomly selected, not just taken 'at random' by hand - fit the above pattern:

The 'Label' and 'L' held the same values in every UMID and could be ignored for now. (I have masked out the 'Label' number together with a portion of the UMID at the end as these contained identifying but irrelevant information about the system.) The 'L' value (0x13) simply stated the number of bytes - 19 in decimal - that followed it. We can therefore ignore both of these parts.

The 'Instance number' and the 'Material number' were far more interesting however. Maybe this might hold some sort of pattern? A counter that goes up gradually perhaps? I noted that the instance number is made up of three bytes, just like HTML colour codes. Maybe the data will be clearer if it was plotted out as colour information, using HTML and a browser? Worth a try!

Let's start with a list of these UMIDs, in a file called 'umids.txt'. You can get a sample file to work with from here. The file contents will look like this:

0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF13354abaf43bfe04396505805ef6FFFFFFFFFFFF

0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF13f558cb8b406d0140650580733dFFFFFFFFFFFF

...

etc

I use python to manipulate and massage data and I use it here so you'll have to install it to follow along on your own machine. (I highly recommend learning the basics of it if you are planning to dig into some data at some point.)

Python 2.7.5 (default, Jul 30 2013, 14:34:22)

[GCC 4.8.1] on cygwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> umid_file = open("umids.txt", "r") # open the umid list for reading ("r")

Now to build up a list of the numbers we care about in a variable called 'umid_list' by going through each line of the file and pulling out the number we want.

>>> umid_list = []

>>> for line in umid_file:

>>> # The digits of the instance number after the 28th character,

... # and ends on the 34th character. We can slice out this section and

... # add it to the umid_list like this:

... umid_list.append(line[28:34])

...

>>>

We now have a list of things called 'umid_list', and each thing is a 6-digit hexadecimal number. If I want to specify a colour using CSS in an HTML page, it would look like this: "color: #cbe4e4;". Let's write a little bit of code to make coloured bars in a webpage, the colours corresponding to the instance numbers:

>>> def bars(html_filename, list_of_stuff):

... with open(html_filename, "w") as htmlfile:

... htmlfile.write("<html><head><style>.bar { width: 100%; height: 0.3em; } </style></head><body>")

... for instance_number in list_of_stuff:

... htmlfile.write(

'<div class="bar" style="background-color: #{0};"> </div>\n'.format(instance_number))

... htmlfile.write("</body></html>")

...

>>> bars("bars_of_umids.html", umid_list)

>>>

Example code to create bar and block HTML pages, as well as means to create random and ordered 'stuff' to visualise can be found here.

What this does is create a method that takes a filename to write to and a list of stuff to use to create the webpage. It opens the file, writes the basic HTML head including the styling for the 'bar'. In this case, it makes it as wide as the page and "0.3em" high - 1 em is the corresponds to the current font size.

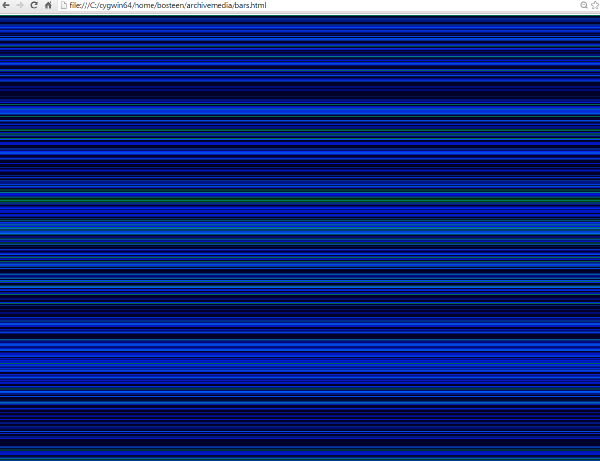

The code then adds an element for each instance number, and styles the element to use the instance number as a background colour. The generated pages look something like this:

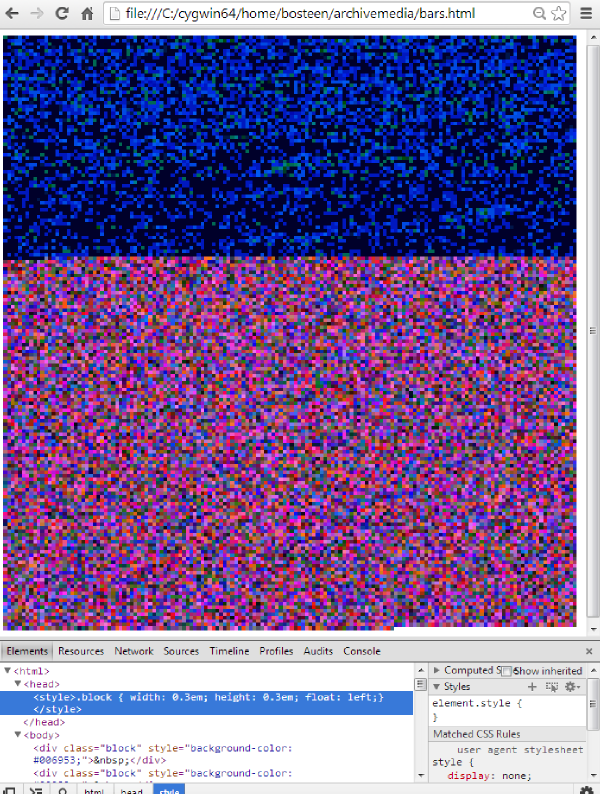

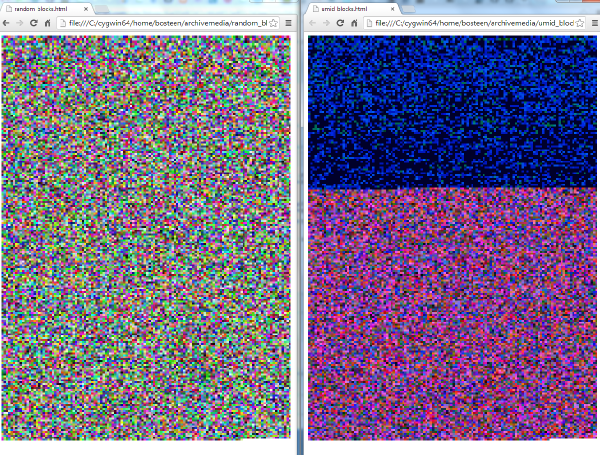

I wasn't able to discern much from this very long page. Instead of bars of colour, how about small blocks of colour? I edited the style information in the browser (via Ctrl-Shift-I in Chrome) to do so and it turned out like this:

This is far more interesting! Note how there is a massive change in the range of numbers used after a certain point and the colours tend towards the red after this point too. Compared to random numbers, the difference is noticeable:

Already, we understand that this section is not random, that there might be some interesting information in there that is worth a little more exploration. The visualisation may not convey any specific information and publishing it may be wasted effort, unless you are writing a piece about usefulness of these intermediate visualisations of course!

Visualising 'Post-Excel' data

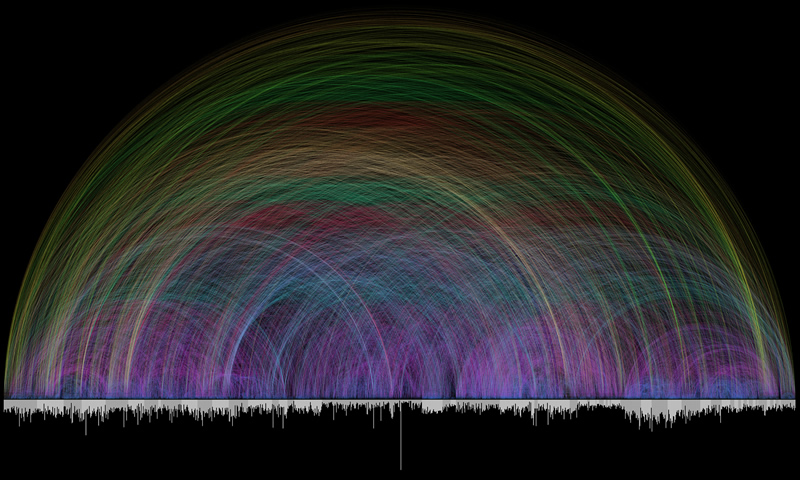

A final example will use the published RDF data from the British National Bibliography (BNB) which comprises around 90 million 'triples'. This is too much information to put into Excel, but it isn't really big enough to count as 'Big Data'. That said, the same toolsets that have been developed to handle the very large datasets are very capable when manipulating these big-but-not-big datasets. I used Apache Pig on Hadoop to do the work. I will skip the details about how I did the number-crunching for now as deserves its own post later!

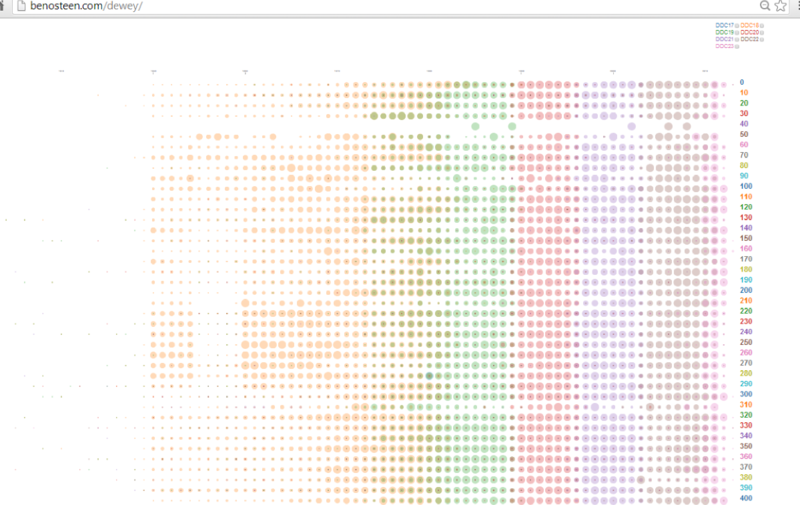

I wanted to know, proportionally, how the number of works in a given subject varies across the years that the BNB covers. In this example, I created a list with rows containing the Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) including the version of DDC, the year of publication and the number of works published in that year in that DDC range. I then created a webpage that uses a javascript library called D3 to draw and place circles on the page to represent this data. As this uses javascript and SVG, the visualisation should work in most normal browsers (i.e. not Internet Explorer).

The DDC17 to DDC23 checkboxes will allow you to hide or show the circles corresponding to the various different versions of the Dewey Decimal Classification. I recommend zooming out (Ctrl -) to get general feel of the entire distribution. Note that for some publication years, multiple versions of the DDC are used to categorise the works, due to the retrospective nature of cataloguing. There are works classified with Dewey that pre-date the entire system.

While this visualisation has done its job and given me and my colleagues a better idea of what is in there, it doesn't answer a specific question as many well-regarded visualisations or infographics do. However, I hope that the usefulness of making these exploratory images has been made clear!

Please comment below if you would like more detail on how I adapted some code from an existing D3 visualisation to create this one.

In summary, try to view your data in a number of ways as you go, rather than just as a means to publish it.