The history of the Sforza Hours, our newest upload to Digitised Manuscripts, in many ways resembles a detective story. The manuscript (now Add MSS 34294, 45722, 62997, and 80800) was commissioned about 1490 by the Duchess of Milan Bona Sforza (d. 1503), the second wife of Galeazzo Maria Sforza. The Milanese court painter Giovan Pietro Birago (fl. 1471-1513) was contracted to embellish it with miniatures.

Bas-de-page scene of a hound chasing a rabbit, with Bona's name 'Diva Bona' in the full border, Add MS 34294, f. 122v

Detail of a full border with Bona's embelm of the phoenix and motto 'Sola fata, solum Deum sequor', Add MS 34294, f. 93r

By 1494 Birago’s work on the manuscript was almost finished and the artist delivered a substantial portion of the still-unbound manuscript to the Duchess. Then, something unexpected happened. Several leaves still remaining in the artist’s workshop vanished. The missing portion must have included a calendar, an indispensable part of any Book of Hours, which the Sforza Hours lacks to this day. At present, the manuscript begins imperfectly with the four lessons excerpted from the Gospels.

Miniature of St Mark and his lion at the beginning of the Gospel excerpts, Add MS 34294, f. 10v

Birago’s version of events surrounding the mysterious disappearance of the illuminated leaves survives in a letter he wrote to a person whose identity unfortunately has not yet been traced. The painter claims that his work was stolen by a certain Fra Gian Jacopo, and subsequently sold by him to another friar, only referred to in the letter as Fra Biancho. This Fra Biancho, Birago continues, took the leaves to Rome and presented them to Giovanni Maria Sforzino (d. 1520), illegitimate son of Francesco Sforza and half-brother of Bona’s husband Galeazzo. The letter not only gives us some insight into the murky behaviour of some ordained members of the Milanese church, but also puts into perspective the tangible value of an illuminated manuscript as a desirable object of theft. Regrettably, the letter does not give us any time frame for the events it describes. We may only suspect that Giovanni Maria Sforzino had already received the stolen leaves by the time of his sister-in-law’s death in 1503, as they were never returned to her or reintegrated with her prayerbook.

It is only now that a small portion of the previously missing folios can be reunited with the rest of the manuscript, if only digitally. Three detached leaves illuminated by Giovan Pietro Birago, all discovered in the 20th century and now in the collection of the British Library, were identified as those once removed from the unbound Sforza Hours. Two of them are leaves from the calendar (Add MSS 62997 and 80800), and were both acquired by Martin Breslauer in 1984, in Switzerland.

Calendar page for May, Add MS 62997

Calendar page for October, Add MS 80800

The third leaf includes a miniature of the Adoration of the Magi that once preceded the hour of Sext in the Hours of the Virgin (Add MS 45722). It belonged to the French collector Jean Charles Davillier (b. 1823, d. 1883) before an anonymous benefactor presented it to the British Museum in 1941.

Miniature of the Adoration of the Magi, Add MS 45722

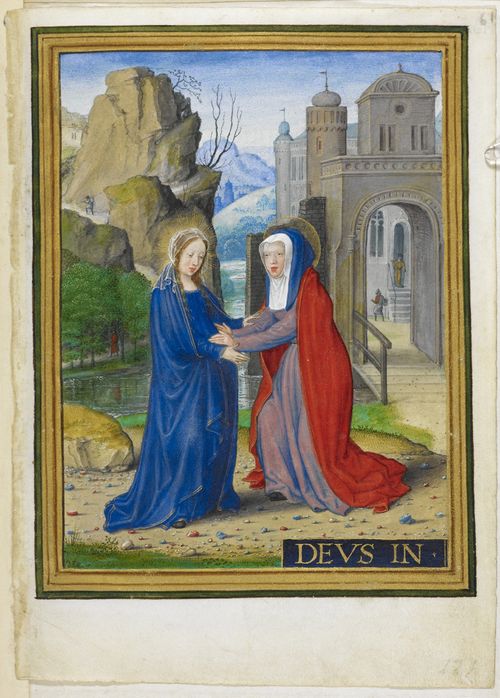

The remaining miniatures by Giovan Pietro Birago have never been recovered. Bona Sforza clearly did not commission another campaign of work to complete her book of hours. At her death in 1503, the unfinished manuscript probably passed to her nephew Philibert II (b. 1480, d. 1504), Duke of Savoy. Philibert must have either presented or bequeathed the hours to his wife Archduchess Margaret of Austria (b. 1480, d. 1530). Margaret, a keen patron of the arts, decided to have the manuscript completed. In 1517, she commissioned the scribe Etienne de Lale to replace some of the missing text, and between 1519 and 1521, the Flemish illuminator Gerard Horenbout (b. c.1465, d. c.1540) to paint the remaining miniatures (the accounts for both campaigns have survived). Doubtless following the Archduchess’s wish, Horenbout painted her and her father’s portraits in a biblical disguise. Margaret appears as St Elizabeth in the Visitation.

Miniature of the Visitation, from the prayers at Lauds, Add MS 34294, f. 61r

She is also recognizable as a woman attending the Presentation of Christ in the Temple, while her father, the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian, is shown as Simeon.

Miniature of the Presentation in the Temple, from the prayers at None, Add MS 34294, f. 104v

The manuscript must have been subsequently presented to Emperor Charles V (b. 1500, d. 1558), Margaret’s nephew. The Emperor's portrait in a cameo bust can be found in the margin of f. 213r with the accompanying monogram KR (Karolus Rex).

Folio with a cameo bust of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Add MS 34294, f. 213r

The Sforza Hours was eventually purchased by Sir John Charles Robinson (d. 1913), Surveyor of the Queen's Pictures, in 1871, in Spain. The book subsequently passed to another art collector, John Malcolm of Poltalloch (d. 1893), who presented it to the British Museum in 1893.

- Joanna Fronska