Part holy shrine, part legendary castle, the Abbey of Mont Saint-Michel is one of the most romantic spots in Europe; it has been a site of miracles and the destination of countless pilgrims for over a thousand years. The story goes that in 708 the archangel Michael told Aubert, the Bishop of Avranches, to build a church on Mont Tombe for him. St Aubert ignored him at first, but the archangel returned and reputedly burned a hole in Aubert’s skull with his finger. The Bishop realized that he could ignore the archangel no longer and Mont Tombe was dedicated to Michael on October 16, 708. St Aubert built the first church on the island and it has been known as Mont Saint-Michel ever since.

Mont Saint-Michel as viewed along the Couesnon River, photo by David Iliff (via Wikipedia Commons, license: CC-BY-SA 3.0)

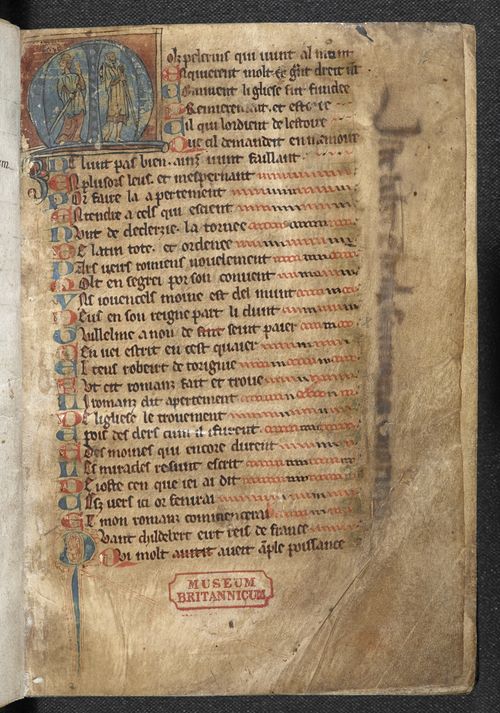

The verse history of Mont Saint-Michel or Li Romanz du Mont Saint-Michel was composed by Guillaume de Saint-Paier, (now Saint-Pois in the diocese of Avranches), who was a young monk in the Abbey of Mont Saint-Michel in the time of the abbot Robert of Torigni, between 1154 and 1186. His work, written in the Norman dialect of Old French c. 1160, is based on Latin texts and charters found in a 12th-century cartulary of the monastery (Avranches, BM 210) and in later copies. In the prologue Guillaume says that he wrote the Roman to instruct pilgrims who did not know the history of the monastery. The British Library has the only two surviving medieval copies of the work and a new arrival on our Digitised Manuscripts website is the earliest copy, which dates from the last quarter of the 13th century (Add MS 10289). This manuscript has been in our online Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts for some time, with a small selection of images, but now every page is available to view. The text is of great interest to historians of Western Normandy and scholars of the Norman dialect, for which it is an early example.

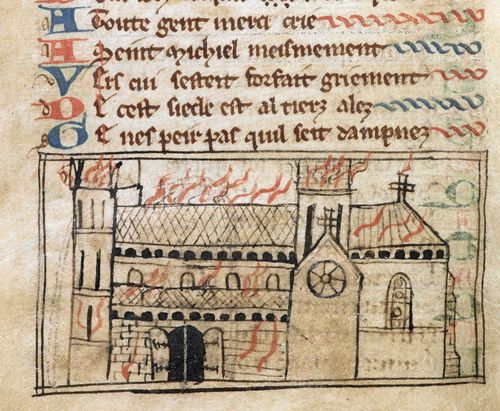

Detail of a painting of Mont Saint Michel burning, from 'Li Romanz du Mont Saint-Michel', France (Normandy), 1375-1400, Add MS 10289, f. 45v

The monastery is shown engulfed in flames in this image in the lower margin. The buildings fell into disrepair after a severe fire in 922 and in 966 Richard, Duke of Normandy, established an order of Benedictine monks there, who started to reconstruct the church. They brought in craftsmen from Italy and started work in 1017. The abbey was finished in 1080 and pilgrims flocked to the island to worship St Michael, even when the abbey was in English hands much later, during the Hundred Years War. The Monks of Mont Saint-Michel were revered for their copying skills and there has been a library there since the 10th century. Our manuscript has an inscription, Iste liber est de thesauraria montis running along the right-hand margin on f. 1, showing that it was in the library in the 15th century.

Historiated initial 'M'(olz) of two pilgrims at the beginning of 'Li Romanz du Mont Saint-Michel' and inscription in the margin, France (Normandy), 1375-1400, Add MS 10289, f. 1r

When the Maurists took over control of the monastery from the Benedictines in the 17th century, they reorganised the books and manuscripts, and they wrote ex-libris inscriptions in many of the books, Ex monasterio sancti Michaelis in periculo maris (‘From the monastery of Mont Saint Michel, in danger from the sea’). But it was the destructive force of humanity, rather than the sea that posed the greatest danger to the monks and their library. During the French Revolution the libraries of nobles and monasteries were confiscated for the public and the 3550 books and 299 manuscripts from the abbey were piled into carts, guarded by the National Guard, and crossed the sands to the mainland. They were piled in a damp storeroom in the municipal offices of Avranches, together with other monastic archives and in 1835, when they were catalogued by la Société d’archéologie d’Avranches, only 199 remained. At this time they were moved to the new Hotel de Ville and remain in the collections of the city of Avranches.

Our manuscript was already in the hands of an English collector, Richard Heber, by this time, and was purchased from him by the British Museum in 1836.

The ‘Romance of Mont Saint-Michel’ is only a third of the volume. The rest is a collection of moralistic and religious texts and medical recipes, including a recipe for a lotion to whiten the skin

Recipe for ‘Ognement espruve por blanchir’ on the lower half of the page, France (Normandy), 1375-1400, Add MS 10289, f. 81v

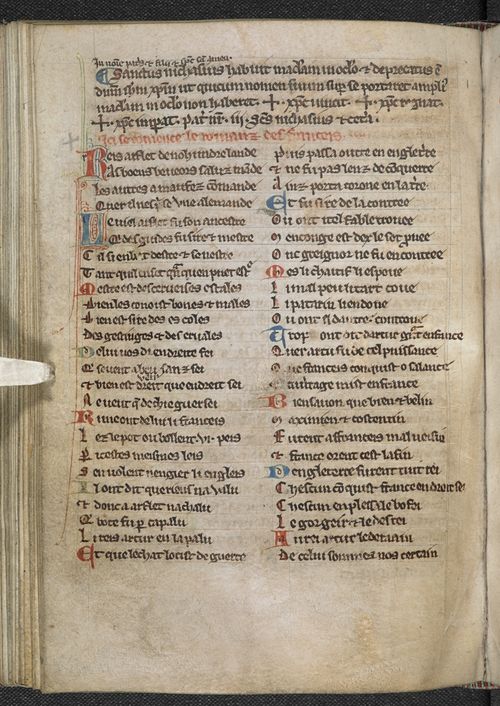

On ff. 129v-132v can be found Andre de Coutances Le romanz des Franceis or Arflet, a violent anti-French satire composed in around 1200. It was written in response to a French satire, in which King Arthur/Alfred is portrayed as Arflet, le roi des buveurs, a drunken Northumbrian king whose crown is usurped by the cat, Chapalu. De Coutances defends the English by attacking meagre French cuisine and mocking their reputation as dice-players and cowards in the face of battle. Their king, Frollo, is lazy and even lies in bed while his boots are being fastened.

The satire begins, ‘Reis Arflet de Nohundrelande...’ and is written in four-line verses or laisses, each beginning with a coloured initial.

Text page with the opening lines of the satire, Arflet or Le romanz des franceis, France (Normandy), 1375-1400, Add MS 10289, f. 129v

- Chantry Westwell