Today marks the 1000th anniversary of the death of King Æthelred II (reigned 978-1016). Æthelred II—often nicknamed Æthelred the ‘Unready’, from the Old English word for 'ill-advised'—has not enjoyed a glowing reputation throughout history.

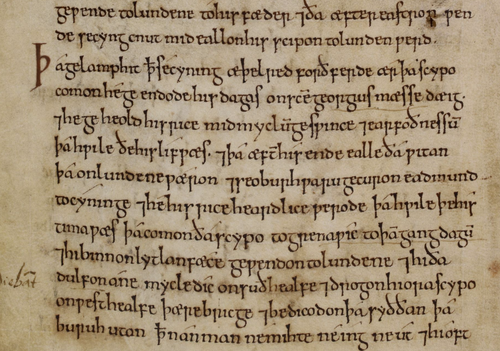

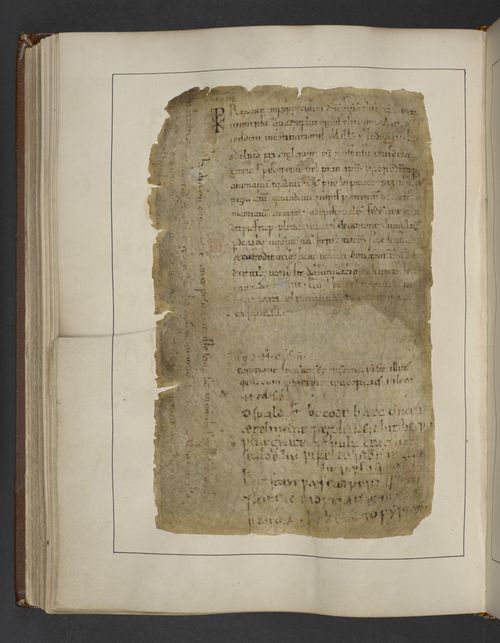

Passage describing Æthelred’s death from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle C-text, England, 11th century, Cotton MS Tiberius B I, f. 153v

The longest narrative account of Æthelred’s reign comes from a group of entries in the C, D, and E texts of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. (The British Library possesses the C and D texts and has recently digitised all its copies of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.) These entries were apparently composed after Æthelred’s death by a single chronicler, who was bitter about the repeated Viking invasions that had dogged Æthelred’s reign and the eventual conquest of England by the Scandinavian leader Cnut. The chronicler blamed Æthelred for many of these tribulations, and summed up Æthelred's life in his entry for 1016 by saying: 'He ended his days on St George's day, and he had held his kingdom with great toil and difficulties as long as his life lasted' (translated by Dorothy Whitelock and others, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: A Revised Translation (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1961), p. 95).

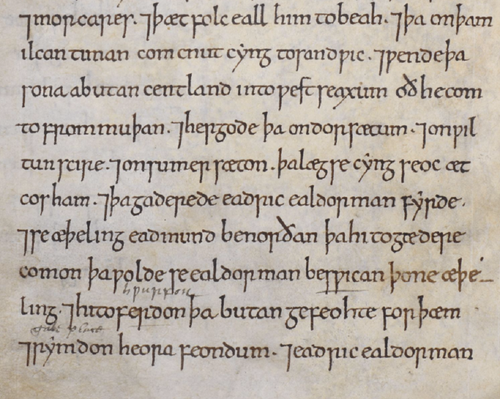

Passages describing Eadric Streona’s treachery from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle D-text, England, 11th century, Cotton MS Tiberius B IV, f. 65v

In particular, the chronicler objected to Æthelred’s promotion of the treacherous noble Eadric Streona, who eventually joined Cnut’s forces. He also disapproved of the massive payments which English leaders collected and used to pay Viking forces in return for an end to hostilities.

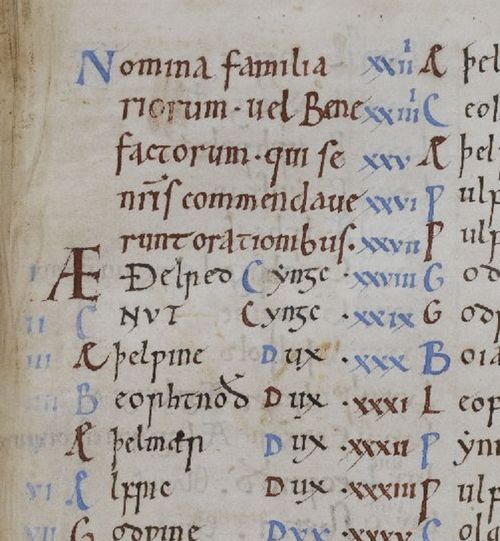

Detail of a list of benefactors including ‘Æðelred [the Unready] Cynge' and 'Cnut Cynge', from the New Minster Liber Vitae, England (Winchester), 1031, Stowe MS 944, f. 25r

Despite the eventual conquest of Æthelred’s kingdom by Cnut, there are other suggestions that Æthelred was not an entirely incompetent ruler. Æthelred was one of the longest reigning early medieval kings: he ruled for approximately 38 years, even taking into account the period when the victories of the Viking leader Swein forced him into exile in Normandy in 1013 and 1014. By contrast, Æthelred’s father, Edgar the Peaceable, had only reigned for 16 years, and Æthelred’s successor Cnut reigned for 19 years. Æthelred’s longevity, particularly in the context of invasion and disruption, is remarkable.

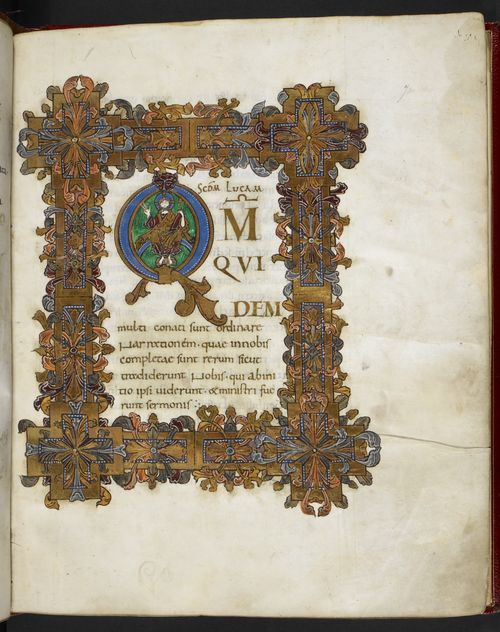

Initial at the start of the Gospel of St Luke, from the Cnut Gospels, England, Royal MS 1 D IX, f. 70r

In addition to disruption, Æthelred’s reign also saw a flourishing of artistic production, as evidenced by several manuscripts in the British Library’s collection, which have now been digitised in full. These include the lavishly illustrated and gilded gospel-book pictured above which may have been made during Æthelred’s reign, even though it is known today as the ‘Cnut Gospels’ because charters of Cnut were later added to it around 1018.

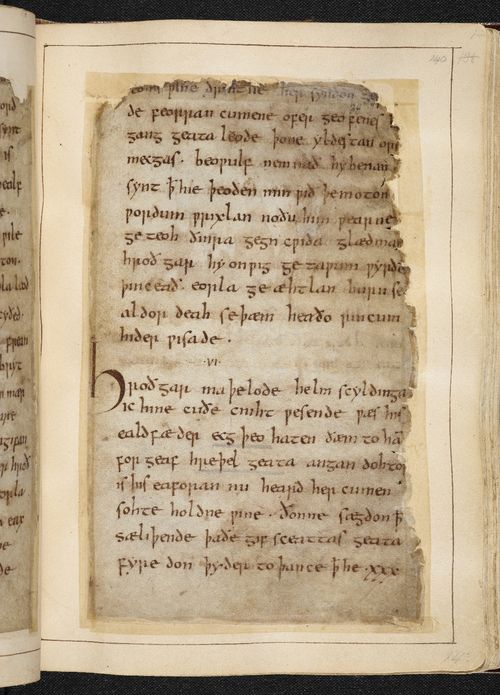

Page from Beowulf, England, c. 1000-1016, Cotton MS Vitellius A XV, f. 140r

Similarly, the only surviving manuscript of the longest Old English epic, Beowulf, was copied during Æthelred’s reign, in the early 11th century. Curiously, Beowulf is a Geatish, or Scandinavian, hero, whose story was still being retold in a context of Scandinavian invasions of England. This manuscript contains a number of other notable texts as well, including an Old English poem about the Biblical heroine, Judith.

Deatil of the opening page of Ælfric’s Life of St Æthelthryth, from Ælfric’s Lives of the Saints, England (? Bury St Edmunds or Canterbury), 1st half of the 11th century, Cotton MS Julius E VII, f. 94v

Indeed, many of the most important works in the corpus of Old English literature were copied during Æthelred’s reign, and some were even produced then. In particular, Æthelred’s reign coincided with the career of Ælfric of Eynsham, one of the most prolific and talented authors of Old English works. Ælfric’s sermons, including his Lives of the Saints, his Grammar, and other texts were widely copied during the 11th century and are still studied in medieval English literature courses today. The British Library has now digitised two copies of the first series of Ælfric’s Catholic Homilies (see Cotton MS Vitellius C V), including the earliest surviving copy (Royal MS 7 C XII); one copy of Ælfric’s Lives of the Saints (Cotton MS Julius E VII); two copies of Ælfric’s Grammar (Cotton MS Faustina A X, Cotton MS Julius A II); a copy of the Old English translation of the Hexateuch, to which Ælfric was a principal contributor (Cotton MS Claudius B IV); and other works which include excerpts from Ælfric, such as a fragment of a colloquy associated him which was copied into the margins of a grammar book (Add MS 32246).

Page from a later copy of Ælfric’s Hexateuch, England (Canterbury), c. 1025-1050, Cotton MS Claudius B IV, f. 15v

Æthelred’s reign also coincided with the careers of other noted writers in Old English and Latin, including Wulfstan, bishop of Worcester and archbishop of York, and Wulfstan, cantor of the Old Minster, Winchester. Manuscripts of these men’s work—including some with additions and annotations in Wulfstan of Worcester’s own hand—have also recently been digitised, including Wulfstan of Winchester’s long Latin poem about the miracles of St Swithun (Royal MS 15 C VII).

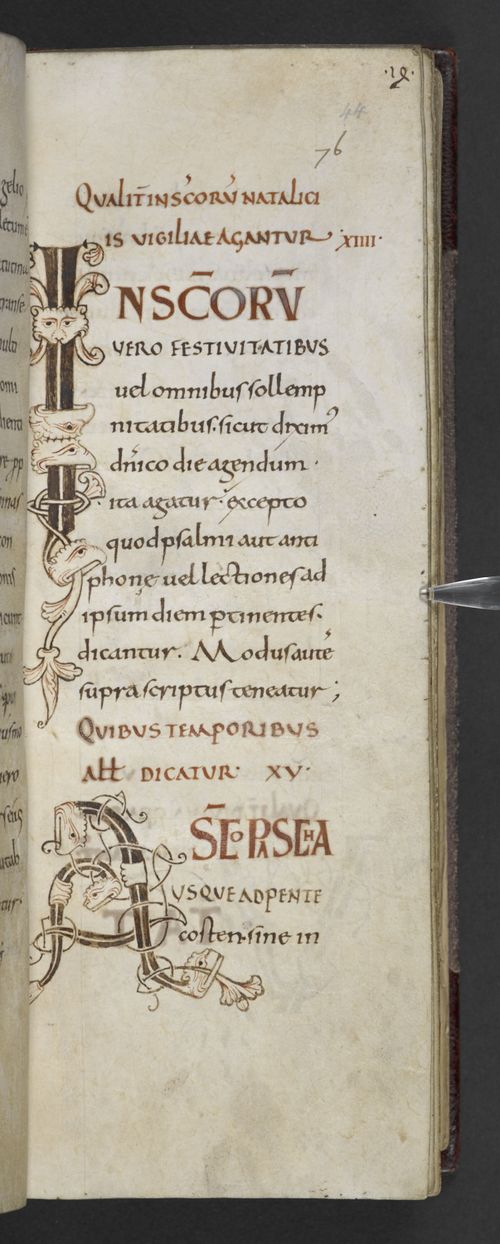

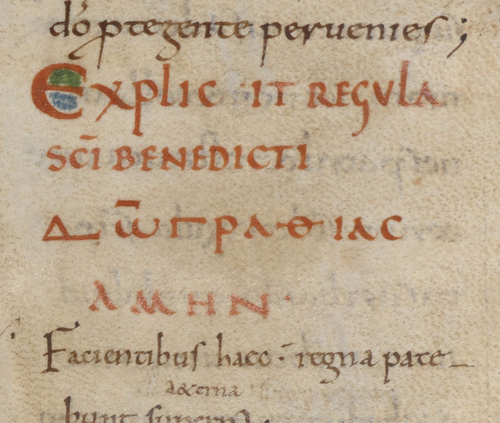

Page from the Rule of St Benedict, England, c. 975-1016, Harley MS 5431, f. 44r

These writers were all products of the monastic reform movement which promoted the Rule of St Benedict, uniformity of lifestyle, and high standards of education. Much manuscript evidence of this learning survives, including a plethora of grammar books, glossaries, and texts on subjects from astronomy (Cotton Domitian A I) to Latin epics to hagiography to riddles.

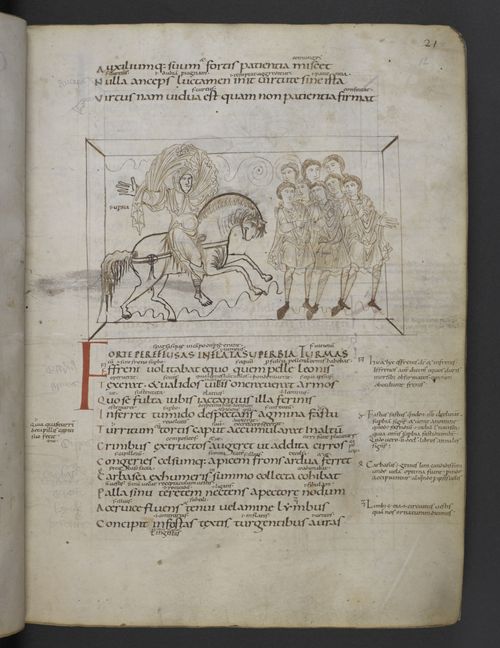

Page from Prudentius' Psychomachia with illustration and glosses, England (? Bury St Edmunds), c. 980-1020, Add MS 24199, f. 12r

These texts show monks (and possibly nuns and lay people) studying and improving their Latin and even Greek.

Latin phrase ‘Deo gratias’ written in Greek letters, from Harley MS 5431, f. 106v

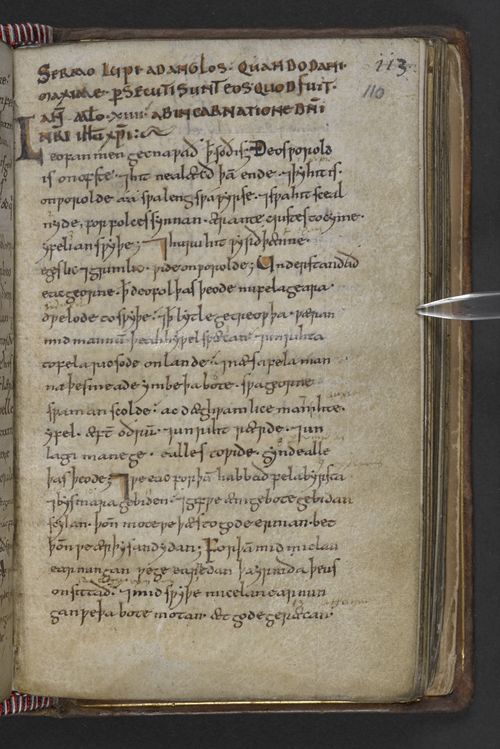

This artistic flourishing was not entirely unrelated to the troubles of Æthelred’s reign. Many members of Æthelred’s kingdom believed that the Viking invasions were divine punishment for lax practices and lack of learning. This view can, for instance, be found explicitly in the writings of another leading intellectual of Æthelred’s reign: Wulfstan, bishop of Worcester and archbishop of York, who wrote several law codes issued in Æthelred’s reign and was a senior administrator for him (and later, for Cnut). Wulfstan’s law codes and his famous ‘Sermon of the Wolf to the English’ blame his countrymen’s lax habits for Scandinavian forces’ recent victories. In the eyes of contemporaries, creating beautiful books to glorify God and educate clerics and lay people may have been one way to combat the country’s moral (and military) woes.

Page from Wulfstan’s Sermo lupi, England (? Worcester or ? York), Cotton MS Nero A I, f. 110r

Beyond the manuscripts related to art and learning, we have also recently digitised a series of documents which suggest that, in some regions at least, leases and property deals and farming continued apace during Æthelred’s reign. Such documents can be found in an early cartulary of Worcester, such as the Liber Wigorniensis (Cotton MS Tiberius A XIII, ff. 1-118v) and the Ely farming memoranda (Add MS 61735). The memoranda describe farm tools and livestock sent from Ely Abbey to Thorney Abbey, as well as rents payable in eels.

Grant by King Æthelred to the Bishopric of St David with reversion to Worcester from 1005, from the Liber Wigorniensis, England (Worcester), c. 1000-1025, Cotton MS Tiberius A XIII, f. 118v

Whatever one thinks of Æthelred, it cannot be denied that his reign was a fascinating time in political and artistic history. On 23 April 2016, when so many people around the world are celebrating the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, it is worth pausing to remember that it is also the 1000th anniversary of the death of King Æthelred.

~Alison Hudson