06 June 2012

The Water Poet, pageants and the Thames

Diamond Jubilee Thames pageant © Tanya Kirk 3June 2012

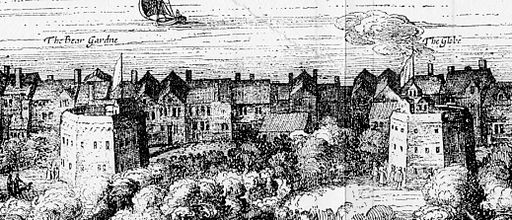

One of the less well-known poets to feature in Writing Britain is John Taylor, the self-styled ‘Water-Poet’. Born in 1578 in Gloucester, he moved to London in his early teens and was apprenticed to a Thames waterman. Watermen were the taxi drivers of the 16th and 17th centuries who, in the days before plentiful bridges across the river, ferried vast numbers of people back and forth between London proper and the theatre district at Bankside.

After a somewhat swashbuckling apprenticeship (at the ages of 17 and 18 he journeyed to Cadiz and the Azores, as part of the group of watermen who were contracted by the navy) he could have just settled down to his profession, but he had other ideas. Taylor decided he would like to be a poet, a sort of Thames poet who would tell it like it is – portraying the river as a dirty but vital force rather than the unrealistically silver “Sweet Thames” portrayed by Spenser and other near-contemporaries.

Taylor’s first book was The Sculler, a collection of poems published in 1612, when he was around 34 years old. It was a cheap pamphlet, featuring a woodcut of Taylor in his boat. The Sculler is currently on display in Writing Britain:

British Library shelfmark C.186.bb.18

(If you're interested, the Latin inscription on the title page is an aggrandised version of the cry of a waterman: "I am the first man. Will you go with me to row? I have the nearest boat.")

In order to finance later works, he hit on a cunning plan. He would perform various crazy stunts, collect subscription money (basically, sponsoring him to carry out the stunt) and use the money to pay the printers. His most famous of these was his attempt to row from London to Quinborough in Kent in a boat made of brown paper, with dried fish tied to sticks as oars. Luckily he also opted for inflated calves’ bladders tied all around the sides of the vessel, or he would probably have drowned fairly quickly.

In 1613 James I’s daughter Elizabeth was to marry. A grand river pageant was devised for the occasion, with some accounts attributing it to Taylor himself. He did write a long description of the pageant and a poem upon the occasion (“Epithalamies”), but made no mention of himself in it – somewhat unusual for such an accomplished self-promoter, if he had indeed had a role in it.

His description of the fireworks on the river focuses heavily on his own explanation of the reasons for describing them, to add to the glory of the King and remind all of his power:

I did write these things, that those who are farre remoted, not only in his Majesties Dominions, but also in forraine territories, may have an understanding of the glorious Pompe, and magnificent Domination of our High and mighty Monarch King James: and further, to demonstrate the skils and knowledges that our warlike Nations hath in Engines, fire-works and other military discipline, that they thereby may be knowne, that howsoever warre seeme to sleepe, yet (upon any ground or lawfull occasion (the command of our dread Soueraigne can rouze her to the terrour or all malignant opposers of his Royall state and dignity.

Taylor’s actual description of the fireworks relies heavily on the phrase ‘many fiery balls flies up into the Ayre’. Other than that, they seemed to have served a very different purpose to fireworks today, being mainly used to represent the re-enacted battle in the pageant, which involved 16 ships, 16 galleys, and 6 frigates. I can’t image people oohing and aaahing over these fireworks; rather, they were meant to be cowering at the power of the Royal Navy.

It all seems a bit less cheerful than the Thames pageant 399 years later (last Sunday). In 1613 they seem to have had better weather but the mock-battle element was a lot more bloodthirsty, and lacked the benefit of an entire boat of Robin Hoods.

Diamond Jubilee Thames pageant © Tanya Kirk 3June 2012

If you’re wondering what happened to John Taylor, he managed to retain his popularity as a poet (albeit a pretty bad one) and his professional career, becoming one of the King’s Watermen; an official spokesman for the Company of Watermen, and publishing a volume of his complete works in the 1630s – a large, grand folio which is an extreme contrast to the cheap quality of his first book. However towards the end of his life his royalist beliefs didn’t serve him well, and he died in poverty in 1653.

You could say that Taylor was about a century before his time. In the 18th and early 19th century ‘peasant poets’ were in vogue, and Stephen Duck (the Thresher Poet), Ann Yearsley (the Bristol Milkwoman) and Mary Collier (the Washerwoman Poetess, also featured in Writing Britain) became popular with the aristocracy as rustically authentic poetic voices. I’m sure Taylor would have seen himself as a cut above the others, but he’d have enjoyed the fame.