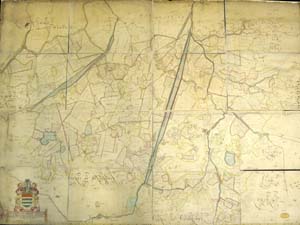

A Map of the Great Levell of the Fenns...by Jonas Moore.

London, 1658 (1824)

copperplate engraving on 16 sheets, 143 x 198 cm.

British Library Maps 184.l.1

There are two perspectives on Jonas Moore's map of the English Fens. On the one hand, it is a very large and dull map of one of the most featureless parts of England, which focuses upon the intensely dull subject of irrigation.

Alternatively, it is one of the real great British maps, a colossally expensive printed map of an up-and-coming part of eastern England, which celebrates one of the most important and multi-national business ventures of the seventeenth century. It even has great in its title.

The map commemorates the draining the English Fenland undertaken by the Bedford Corporation from the 1630s. The project promised the development of vast areas of rich pasture land (big money stuff), and involved a lot of digging, channelling and sluicing, planning, negotiation and investment.

Sir Jonas Moore (1617-1679), an ambitious man of surveying and mathematics, produced the map to commemorate the success of the project, finished by 1656 and approved by the appointed commissioners. The investors got their return (unsurprisingly, since many of them also sat on the commission), and there was much rejoicing. They also would have got a copy of the map to put on their wall as a symbol of their success. If you look at the map, you can see the newly-dug channels stretching diagonally across the land, carrying the excess water out to sea; incredible, almost violent changes wrought upon the land. The project had literally changed the face of the land, and the map proves it. This was big-business, 17th century style.

Only one example of the first edition of the map survives, in The National Archives at Kew. This has the arms of each of the investors around the edge of the map, which were removed from subsequent printings as many of the men were to see their positions compromised with the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. The map was re-printed a number of times, even as late as 1824, suggesting that a century-and-a-half later it had assumed an almost iconic significance.

Moore's map has been termed 'a giant amongst early English printed large scale topographical maps,'

but magnificent? The jury's still out.