This is the text of a talk I gave on 29 January 2016 at the Institute of Historical Research's 'The Production of the Archive' conference. The conference sought to "bring together historians, archivists and scholars from other cognate disciplines to explore shared understandings of the nature of the archive, which is highly topical as archives shift from the traditional fixity of text to the fluidity of multi-faceted digital objects."

Good afternoon. My name is Luke McKernan, and I am Lead Curator for News & Moving Image at the British Library. I’m going to talk about something that has interested me for some while, which is the changing scale of audiovisual archiving. I'm going to do so by looking at two things: YouTube, and web archiving. I'll conclude by considering how historical enquiry and archival care may combine to understand the audiovisual archives we are building for ourselves now.

Film archiving traditionally has been a painstaking business. When films were produced on film, then the objective was to acquire adequate materials to enable the archivist to reproduce the film as closely as possible to the form in which it was originally produced, ideally from an original negative. There were many challenges for the film archivist. National film archives did not really get underway until the 1930s, meaning that much of the first 40 years of cinema was destined to be lost. In the United Kingdom, there is no legal deposit legislation in place for film, so film archivists have had to go out to producers, distributors and collectors to obtain suitable film copies, and not everything has been collected. This is also a costly business, since filmstock is expensive, and bulky, requiring specialist storage conditions as well as specialist equipment to ensure its long-term survival.

The situation, from a statutory point of view, is a little better for television, since a national television archive was enshrined in the 1990 Broadcasting Act. Videotape is also cheaper than film. The expense of film, combined with the distribution models to cinemas, constrained what could be produced, and consequently what could be archived. Television had a different distribution model, one which allowed it to broadcast content non-stop across multiple channels, but the medium for capturing this - tape – was adequate to the task. Very broadly speaking, our moving image archives were able to meet the challenge of archiving much of what was produced, assuming that they were resourced properly to do so.

Over the past ten years, the picture has changed utterly. What has changed it is YouTube, founded in April 2005, and what it has changed relates to scale, content, description, discovery and expectations of access.

Firstly scale. There are just under one million films and television programmes held by the BFI National Archive, the UK’s national moving image collection, collected over eight decades.. By wild contrast, I estimate that there have been 2.7 billion videos uploaded to YouTube since 2005. 400 hours of video are added to the site every minute. There are some film collections out there who haven’t managed to collect more than 400 hours of content in years. In one year in the UK, there are approximately 700 films given a cinema release, 6,000 physical videos published, and about 600,000 television programmes broadcast (excluding repeats). It is not known what proportion of YouTube’s possible 2.7 billion is British in origin, but the number is certain to dwarf that produced by traditional means. Does this render the traditional film archive meaningless, or reductively niche?

Citizen Kane vs Charlie Bit My Finger

So, secondly, content. Vast amounts of this online content is what might be termed trivia: ephemeral videos of skateboarding pets of the kind that would never have been acquired by a film archive, nor even conceived of as a type of film production before the YouTube era. But is it trivia? How are we to judge what a moving image should be? Is the understanding of it as an art medium, of the kind best revered in a cinematheque, now something absurdly narrow? What, intrinsically, is the difference between, say Citizen Kane and Charlie Bit My Finger? Perhaps we should only look at the numbers – unless it is the numbers that are scaring us, and we prefer to cling to old certainties.

When it comes to description, things become problematic. The metadata for videos on YouTube and other video platforms is generally very poor. What metadata there is relates chiefly to when and in what form the video was uploaded to the site, with additional, often entirely random classification terms added by the uploader. The traditional archive puts far greater value on the specificity of the objects in its care.

Discovery and expectations of access are where the deep change lies. YouTube gives you everything, or at least it appears to do so. Access to moving images traditionally has been exclusive, even challenging. The films have been hard to track down, expensive to access, difficult to share. Now anything you can think of is there instantly, arranged in channels or discoverable individually. If a video is not there, it is effectively invisible, not worthy of consideration. A false sense of permanence has been inculcated - that every video is there, and that every video will always be there, with the concomitant reaction by many scholars that if a video is not on YouTube then it is not worth bothering, or necessary, to seek it elsewhere.

But not only is YouTube not infinite, but it is also shedding content on a massive scale. An unknown number of videos is taken down from the site every day, because of copyright infringement, or changing priorities of some publishers, or the embarrassment of those who have decided to hide away some of their youthful indiscretions.

No figure has ever been supplied by YouTube on just how much disappears from the site, but I can give a personal example. I manage a website, called BardBox, which curates original Shakespeare videos to be found on YouTube, Vimeo and other platforms. They are videos of all kinds: original creations, mashups, fan videos, animations, actualities - representative of the broad mix of YouTube genres. Recently I had a spring-clean of the site to check out how many of the videos were still active, and a quarter was no longer there. Has 25% of YouTube disappeared?

Is YouTube an archive? It is and it isn't. It is a repository for cultural content, which it maintains even if the videos are subsequently withdrawn, and although the files it holds are of a lower resolution than the original videos. It provides access. The scale of what is maintains is unprecedented, utterly dwarfing all that preceded it. It seems to be there for the long term. What it fails to provide is certainty. If it is an archive, it is a new kind of archive, one with built-in impermanence, a vast repository for uncertain times.

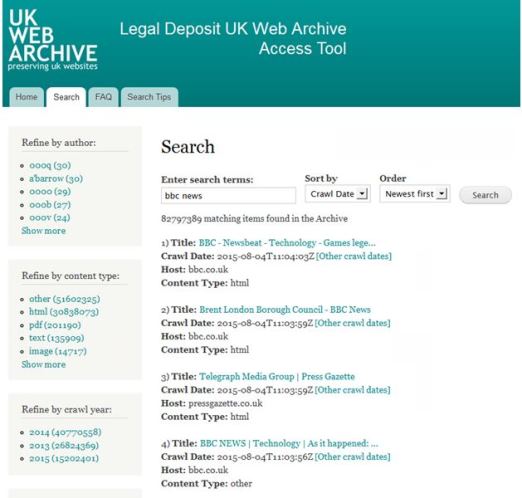

Legal Deposit UK Web Archive

Now let us turn to web archives, which is where the British Library’s interest comes in. In 2013 non-print Legal Deposit legislation was passed which enabled the British Library, working with the other legal deposit libraries in the UK and Ireland, to begin archiving the UK web. There are around 4 million websites in the UK, and most of these we take an archival snapshot of once a year. The result is some 2.5 billion web pages in the Legal Deposit Web Archive. The British Library promotes itself as having some 150 million objects in its collection, but that refers to physical objects and is of increasing irrelevance in a digital age. Numerically speaking, it might be more sensible to describe the British Library as a large digital archive, with a few books on the side.

The 2013 Legal Deposit act excluded video and sound, for a variety of reasons. In practice this means that we do not archive websites which are predominantly video and audio-based, such as YouTube, or iPlayer. But if an audio or video file is incidental to the purpose of a website or webpage, then it can be collected. The result of this can be seen in the figures for the moving image collection that I manage. The conventional collection – which is a mixture of news and sound-based videos – numbers around 100,000 titles. If I add videos gathered incidentally through web archiving, the number rises to half a million. A further 40,000 videos is added every month, so that by this time this year we will have a collection of a million videos.

The situation is similar for sound. The Library holds the national sound archive, a collection of some 6.5 million recordings. In probably no more than four years time, there will be more sounds in the web archive than there are in the traditional sound archive.

What then is an audiovisual archive? Is it the archive gathered by traditional means, in which the best-quality material is selected through curatorial guidelines, to ensure a representative collection of optimum preservation quality? Or is it the random vastness of the web archive, in which videos of low image quality, minimal metadata and frequently spurious significance, are contained within a larger archive of web texts? Should we sacrifice quality of image for quantity of content, or should we maintain principles of selectivity, so that the best content is preserved in its optimum form? Should the traditional archive and the web archive be developed separately, or should they be managed collectively, and if so what does this mean for curation, collecting policies and the scholars who use such resources?

An archived web page with missing video element

These are largely theoretical questions at present. The Legal Deposit Web Archive is in its infancy. Discovery of the archives, which is restricted to terminals in the reading rooms of the various legal deposit libraries, is in need of considerable improvement before the archive can be properly used for research, and resource limitations mean that we’re not even able to playback those audio and video files as yet. Moreover, most researchers aren’t interested in web archives as yet because they have the real web that they can use.

But gradually the realisation will sink in that websites do not last (the average lifespan of a web page has been estimated at around 70 days), and that what was present has become the past, when historical enquiry of the web archives will begin in earnest.

When that point comes, we will have a new kind of audiovisual archive. It will be one that puts audio and video in their contexts. The great limitation of audiovisual archives has been is that is all that they are. They are dedicated to their medium alone. This is fine when the interest is only in the medium, which means chiefly when it is viewed as an art form. But film is equally important for its subject matter, and for that it requires context. Film of itself is meaningless - we have to describe it, to put words to it, for its images to signify something. This is why video has come into its own in the web era - not simply because of the volume of content, but because of the contextualisation. Videos have to be embedded somewhere, and in the embedding they find their meaning. Traditional film archives take the medium out of its original exhibition context; web archives preserve that context.

At present we have film and sound archives that stand alone. They represent their particular medium; they defend its special identity. Some film and sound archive have been absorbed within larger archives, as happened when the British Library took over the National Sound Archive in the 1980s. The sound archive ever since has played a balancing act between integration within the Library's systems and maintaining its separate identity. The national film archives of Wales and Scotland have been incorporated within their respective national libraries, and have faced a similar challenge.

But this slow process of change is going to be rapidly overtaken by the growth in web archiving. In one year's time web video at the British Library will outnumber the remaining moving image collection by ten to one. It will be 15 to one the year after that, and so on, exponentially. I can ignore this upstart archive, or I can engage with it, and to do so I need to learn from researchers of every kind, but particularly historical researchers, how to understand what we are inheriting, how to manage it, how to explain it, how to make it discoverable and most useful. The British Library is engaging with scholars on how to use the web archive now, ranging from subject specialists to big data analysts. But I am interested - and I hope others will be interested - in what the future web archive will look like, and especially how it will operate as a repository of rich media.

As a society we are generating videos at a colossal rate, and look likely to do so at an ever increasing-rate in the future. Archives built on the traditional model cannot cope with the scale of this. The web's video platforms, such as YouTube, offer the illusion of the optimum archive, but they fail to offer adequate descriptions, context or permanence. As scholars we must be wary of them; we certainly must not rely on them.

The web archive, however, promises to be transformative in how video (and audio) contribute to future understanding, because they will be wholly embedded in the archive. The numbers will be vast, but the numbers for every kind of archival digital object we are now generating will be vast. We'll just have to deal with it. What web archiving may promise, though, is the end of audiovisual archives as we know them. Once text, image, audio and video are all preserved as one, why should we specialise? That's the question that lies at the heart of the future management of digital archives. Hopefully it will take just a little longer than the end of my professional life before we decide on the answer.