The death mask of the artist Joseph Mallord William Turner (b.1775), who died on 19 December 1851 at the age of 76, is held at the Tate Gallery in London. An image of the mask can be seen here.

Taut and puckered, Turner’s skin appears tissue-paper thin; his eyes hollowed, nose pinched, his mouth a shrunken and toothless cavity. It gives nothing of the man who is widely regarded as one of the most important and imaginative painters of his age.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway, 1844, oil on canvas, National Gallery, London

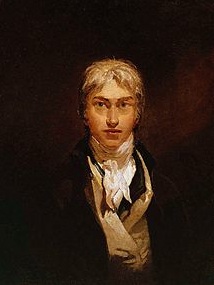

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Self Portrait, c.1799, oil on canvas, © Tate, London 2015

Much has been written about Turner’s career, his enigmatic character, prolific output and his ‘genius’. This blog explores the ‘twilight’ phase of the artist’s life, to the man aging and ailing.

As Turner approached 70 he was beset by periods of ill health. He dreaded the physical deterioration associated with ageing, calling ‘Mr Time’ his ‘Enemy’. ‘Time always hangs hard upon me’, he wrote in one letter, ‘but his auxiliary, Dark weather, has put me quite into the background’. Winter’s chilly gloom and shortened days were Turner’s black beast, and the season’s ‘rigours’ rendered him physically vulnerable.

In a letter held here at the British Library Turner expresses his frustrations to a friend after having caught a bad flu, one of many illnesses to blight him during the winter months. ‘I am now more than an invalid and Sufferer’, he writes, ‘Sir Anthony Carlisle [a pioneer of geriatric medicine]...says I must not stir out of doors until it is dry weather (frost)...or I may become a prisoner all of the Winter’ (British Library, Add MS 50119).

Turner’s winter health never much improved. Though weakened, he lived on, even surviving a severe bout of cholera a year before his death. By then the artist is also thought to have suffered from diabetes, perhaps induced by his well-known propensity for sherry, and was toothless as the death mask shows. Gums tender, Turner survived on pints of rum and milk and sucked meat for sustenance.

In the winter of 1850 Turner found it increasingly difficult to walk. He complained of ‘Gout or nervousness...having fallen into my Pedestals’. Until it became impossible, however, the artist made every effort to attend Royal Academy meetings, lectures, student tutorials, and social gatherings with friends and patrons. His mind and creative faculties never diminished, though critics persistently associated the abstract painterly style of his later years with senility, even derangement.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, The Angel Standing in the Sun, exhibited 1846, oil on canvas, ©Tate, London 2015

Three weeks before Turner’s death Dr Price, the artist’s physician, diagnosed a heart ‘very extensively diseased’. When Turner was informed that his life was ‘fast ebbing’, he turned to his doctor, ‘looking hard at him with his little lustrous eye’ and said: ‘had you not better take a glass of sherry?’ When Price returned, sherry in hand, Turner asked: ‘so I am to become a nonentity, am I?’ in a dry retort. Price responded in grave tones, confirming the diagnosis. Turner replied, ‘I think you had better go and have another glass of sherry’.

Turner was by this point bed bound. He was restless and agitated, eager to sense weather, to see the sun, at least from his bedroom window if not from outside. At the Chelsea house in which he died the artist had very early on installed a roof terrace specifically for sky-viewing and ‘sun-staring’. He would wake before dawn and ascend to the roof with a pocketbook in hand to sketch the day’s sunrise. Turner’s life-long habit of doing just that, however, had resulted in cataracts. This impairment was another physical condition his detractors seized upon to account for the stylistic changes and apparent excessive use of yellow in his later paintings: the ‘fruits of a diseased eye’ they sneered.

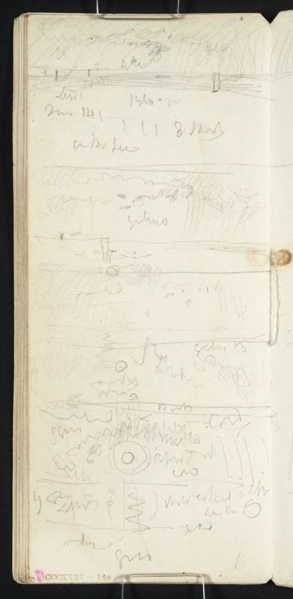

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Sun Setting (or Rising), from Lake of Zug and Goldau sketchbook (Turner Bequest CCCXXXI; folio 16 verso), c.1841, pencil on paper, ©Tate, London 2015

John Wykeham Archer, House of JMW Turner at Chelsea, 1852, watercolour on paper, British Museum, London

On the morning of 19 December 1851 Turner lay in bed attended by his partner Sophia Booth and the locum Dr William Bartlett. ‘Just before 9 a.m.’, Bartlett writes, ‘the sun burst forth and shone directly on him with that brilliancy which he loved to gaze on’. The artist died shortly after ‘without a groan’. Turner’s body was taken to his former house at Queen Anne Street and placed in the gallery he had established there, his coffin surrounded by paintings. Friends and family paid their respects before the funeral at St Paul’s Cathedral.

WA1881.349 George Jones, Turner’s Body Lying in State, 29 December 1851, after 1851, oil on millboard, © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

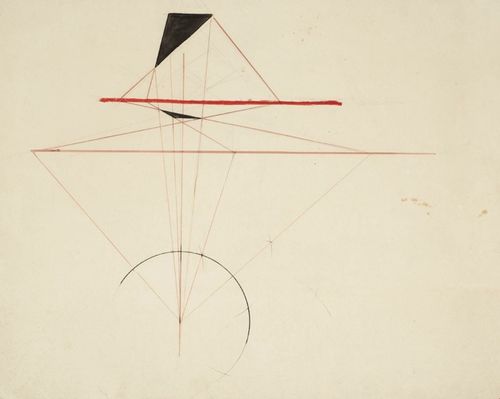

The force that drove Turner in his later years came from a sense of responsibility to his fellow artists and to students at the Royal Academy of Arts where he had trained and where for 30 years he was Professor of Perspective and Geometry. He called this community ‘my brethren in the Vineyard of the Fine Arts’. The British Library holds important documents which demonstrate Turner’s commitment to art pedagogy: a series of 28 manuscripts, in draft and copy, which formed part of the six annual lectures he gave to RA students and fellows throughout his professorial post (Add MS 46151 A-BB). The artist also desired that his works be kept together after his death and exhibited for the benefit of the public in ‘Turner’s Gallery’. This body of work, of which works on paper alone comprise 37,000 accessioned items, was taken into the possession of the National Gallery after 1851. It is now held in the Clore Gallery at Tate Britain. The material at Tate and the British Library is publicly accessible, available to view first hand, just as Turner had wished it in his will.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Lecture Diagram: Perspective Representation of a Triangle, c.1810-28, pencil and watercolour on paper, ©Tate, London 2015

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Lecture Diagram 36: Basic Perspective Construction of a House, c.1810, pencil and watercolour on paper, ©Tate, London 2015

Alice Rylance-Watson

Transforming Topography Research Curator at the British Library and Turner Bequest Cataloguer at Tate Britan

#OnThisDay #JMWTurner #Turner #Deathmask #OTD