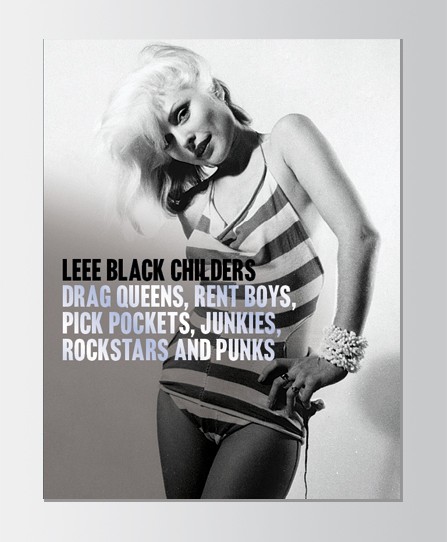

Leee Black Childers, Drag Queens, Rent Boys, Pick Pockets, Junkies, Rockstars and Punks, published by The Vinyl Factory/The Society Club

Archives are strange, and one of the strangest things about them is how lively they can be. On 6 April this year, the photographer Leee Black Childers died in Los Angeles at the age of sixty-nine. He was a legendary figure, a charming Southern gay man who captured the exuberant, seedy glamour of New York in the Sixties and Seventies, photographing drag queens, pop stars, rent boys, junkies, punks and miscellaneous downtown divas.

I first came across Childers by way of the Hall-Carpenter archive, a wide-ranging and insufficiently celebrated work of oral history about gay experience in the UK, which began in 1985 and is now housed at the British Library. Not all the participants were as talented or as well-connected as Leee, but they were meticulously interviewed and as such the archive forms a luminous portrait of queer life across a turbulent century. Still, Childers's long, roaming interview, recorded in 1990, must be among the most electrifying, providing six hours of gripping, moving and frequently scandalous listening.

Leee was born in 1945 in Jefferson County, Kentucky. At the beginning of his tape, he describes the grandmother who raised him, a puritanical figure who claimed she only had sex five times, once for each of her children, and who on seeing a woman wearing trousers remarked: 'Well look at that! They'll be gluing a doodle-whacker on next.' Leee, who began spelling his name with the eccentric extra 'e' as a small boy, fled this narrow-minded world in his early twenties, drifting to San Francisco, where he was involved in the civil rights movement and the hippy scene.

After a spell living with the Black Panthers, he moved to New York, where he began photographing drag queens and soon found himself drawn into the maelstrom of Warhol's Factory. Childers is refreshingly matter-of-fact about his old friend Andy, who he claims became an film maker in order to persuade attractive people to take their clothes off (On the subject of the 1964 Brillo Box sculpture, he comments wryly: 'It was a Brillo box. That's all it was. It was just a Brillo box.') Later, he worked as a tour manager for the likes of David Bowie and Iggy Pop, taking iconic photographs of punk and New Wave figures, among them Patti Smith, Lou Reed, and Debbie Harry in a stripy bathing suit.

He lived at the heart of what was by any standards an extraordinarily flamboyant scene, and it makes for a disorientating experience to sit in the calm surrounds of Humanities 2 in the British Library, listening to Leee describe the goings on – at the Anvil or in the backroom of Max's Kansas City, where the waiters used to complain that every time they went to get fresh napkins they'd find people having sex in the linen closet. Childers is a witty, affectionate guide to this lost period, with its curious mix of innocence and wildness.

He was always drawn to drag queens and they are the subjects of some of his finest work. He was present at the Stonewall riots, an uprising that kick-started the modern-day gay rights movement. The riots began in the early hours of 28 June 1969 in New York, after police raided the Stonewall Inn. 'They were lining the drag queens up behind the bar,' Leee explains. 'This is something I think people should realise. It comes down to drag. All the gay people were walking out meekly, when the drag queens behind the bar started throwing bottles. It was the drag queens who started that riot and it was the drag queens who led it... I wouldn't have missed it for anything.'

So what happened to this electric, electrifying world? In a word, Aids. Leee, who was living in London at the time of the interview, provides an intimate, agonising history of the Aids crisis as it obliterated his community, killing friends and acquaintances and destroying an entire cultural milieu. At one point, he comments: "Every time I open the mail, someone else has died." When I first listened to his tape, I'd been researching Aids and art for two years, but there were still names among his litany I'd never heard before, including the drag queen Brandy Alexander and the beautiful Hibiscus, who went from being a Sixties flower child to a radical performer in the San Francisco dance troupe The Cockettes, performing in full make up, dress and lavish beard.

I suppose this is the point of archives, and the point too of work like Leee's: that it resists obliteration, keeping what is always threatening to disappear in view. His subjects lived at a tilt to society, transgressing social norms of sex and dress and self-presentation in ways that remain subversive even now. His portraits capture this, exuding a magical liveliness, a reckless and informal solidarity. However edgy the subject matter, they're never prurient or voyeuristic. Tennessee Williams used to say: "Nothing human disgusts me unless it's unkind." The same non-judgemental sensibility informs all Leee's work, a kind of radical broad-mindedness that's getting rarer every day.

Olivia Laing is the 2014 Eccles Writer in Residence at the British Library. She's the author of To the River and The Trip to Echo Spring and is currently working on The Lonely City, a cultural history of urban loneliness.

See also the Lee Black Childers SaMI recording.