07 April 2014

Shaikh Ahmad goes to England: The Politics of Official State Visits

In October 1919, on the first night of his official visit to Britain, Shaikh Ahmad Al Jaber Al Sabah, nephew of the ruler of Kuwait, Shaikh Salim Al Mubarak Al Sabah sat unhappily in a hotel room on the outskirts of London. An error in communication during the build-up to the visit meant that officials in London had only been informed of Ahmad’s arrival one day before he actually arrived. By this time, all of the luxury hotels in central London normally used to host foreign dignitaries like the Shaikh had been fully booked and after hours spent driving around London searching, the only accommodation that could be found was a small hotel in the South London suburb of Norwood.

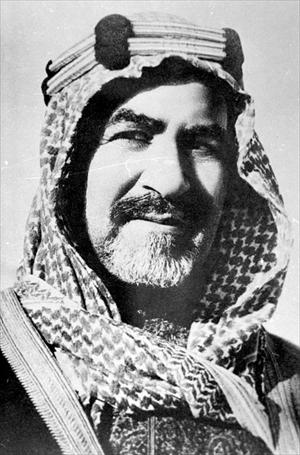

Shaikh Ahmad Al Jaber Al Sabah (1885-1950) later in life. Ahmad was the ruler of Kuwait from 1921 until his death

At this time, Kuwait was a British-protected state that was of significant strategic importance to the British Empire and Ahmad – already one of the most important figures in the country –was widely considered to be the member of the Al Sabah family most likely to succeed his uncle as its ruler. Therefore, in an attempt to ensure that their dominant position in the country would continue unchallenged, the British were keen to develop a close relationship with Ahmad in advance of his succession.

It was for similar reasons that Faisal bin Abdul-Aziz Al Saud of the Nejd, the thirteen year old son of Ibn Saud (and future king of Saudi Arabia, 1964-1975) had been invited to visit Britain at the same time. Inviting members of ruling families, such as Al Sabah and Al Saud, to make official visits to Britain was a common tactic employed in this period as a means to incorporate them into the British imperial system. The visits sought to generate a sense of personal allegiance to the British Empire and to display the grandeur, power and modernity of the metropolis at its heart, London.

Daniel Vincent McCallum, the British Political Agent in Kuwait, was back home in Britain on leave at the time of Ahmad’s visit and two weeks into the trip, he took charge of supervising the Shaikh and his small entourage for the remainder of their visit. An account of the trip written by McCallum is preserved in the India Office Records (IOR) held at the British Library.

According to his account, although Ahmad had been moved out of the hotel in Norwood to a town-house in Pimlico after one night, two weeks into his trip, he remained “very depressed”. Though he had visited the Houses of Parliament, Greenwich Observatory, Westminster Cathedral and several other attractions, he had a long list of complaints against the officials who had been charged with his care.

Another account of Ahmad’s visit, written by Dr Charles Stanley Mylrea, a medical doctor and missionary at the Arabian Mission of the American Reformed Church, is contained in the IOR files. Published under the title “Shaikh Ahmed goes to England” in Neglected Arabia, the Arabian Mission’s own journal, the article speculated that the weather in London may also have played a role in causing Ahmad’s depressed state of mind.

Mylrea discusses the impact of London’s weather on Shaikh Ahmad and some of his impressions of Britain. IOR/R/15/1/504 f.131

McCallum took Ahmad and the Kuwaiti party to visit Hampton Court Palace, the theatre and London Zoo where, Mylrea comments, “it must have tickled his [Ahmad’s] Arab heart to see camels on view as curiosities”. The group also rode on the London Underground which, according to Mylrea, was a “source of real wonder” to Ahmad who had never previously left the Gulf region. In their accounts, both McCallum and Mylrea observe that Ahmad thoroughly enjoyed visiting the cinema and in the words of Mylrea, “patronised one of the picture-palaces almost every night”. McCallum’s letter also reveals that much of Ahmad’s final week in London was spent shopping.

McCallum discusses Shaikh Ahmad’s activities during his final week in London. IOR/R/15/1/504 f. 125

According to Mylrea, Selfridge’s “that huge Anglo-American department store on Oxford Street” was a “popular haunt” of the Shaikh’s. He is said to have been particularly amused by “the sales-girls […] demurely dressed in black”.

Selfridge’s Department Store in Oxford Street, London, that Shaikh Ahmad frequented in October 1919. It remains popular with visitors to London from the Gulf to this day. Imperial War Museum D 23005

The most important component of Ahmad’s visit was his official appointment with King George V at Buckingham Palace. A précis of the speech that Ahmad gave to mark the occasion is contained in the IOR files as are details of the gifts that he offered to the King; a sword that formerly belonged to a Shah of Persia, a golden dagger and an Arabian stallion that Mylrea dryly observes “for obvious reasons was not personally tendered in the audience chamber”.

Précis of Shaikh Ahmad’s speech delivered to King George V, 30 October 1919. IOR/R/15/1/504 f. 129

In return for his gifts, Ahmad received a signed and framed portrait of King George to deliver to his uncle, Shaikh Salim. McCallum observes that while Faisal and the Nejd delegation had spent eight minutes with the King, the Kuwaiti party were granted seventeen minutes and that the Kuwaitis – who had timed the events – considered this a “great score over the others” and were delighted.

Coronation portrait of George V, oil on canvas by Luke Fildes (1843-1927). Royal Collection RCIN 402023

Despite the visit’s inauspicious beginning, McCallum – who enjoyed a good relationship with Ahmad – managed to rectify the situation and in his account was able to conclude that he believed it had done Ahmad “a very great deal of good […] if we pay him sufficient attention in the future I have no doubt when his time comes we will have a really good friend”. McCallum’s effort was to prove worthwhile as in 1921, three years after Ahmad’s visit, he succeeded his uncle as ruler of Kuwait and was to remain in power for almost thirty years until his death in 1950.

Ahmad’s visit typifies the manner in which official state visits – combined with ritualistic gift-giving and ceremonial audiences with the ruling monarch – were used by the British as a means to impress, befriend and co-opt the ruling elites of their numerous client and vassal states from around their global empire.

Primary Source

British Library, ‘File 53/32 III (D 53) Miscellaneous Kuwait correspondence’, IOR/R/15/1/504

Louis Allday, Gulf History and Arabic Specialist,

British Library/Qatar Foundation Partnership

Twitter - @Louis_Allday

This is a very nice summary of an interesting and revealing chapter in Kuwaiti-British relations. I have written a biography of Ahmad Al-Jaber Al Sabah (as yet unpublished), and am quite familiar with the sources dealing with this trip. Two points require some clarification. First, Ahmad was selected for this honour not because he was expected by the British to be the next ruler. That was still an open question at this point. In fact, the ruler of Kuwait, Salim Al Mubarak Al Sabah, had for a while been attempting to convince British officials that his son, Abdullah, should be the next ruler, not Ahmad. But the British pressed their preference for Ahmad in a number of ways, including the decision for him to make this trip. Also, the imbroglio regarding accommodations for the 'Arab Mission', as it was known at the time, arose not because of last-minute notice. British officials in the Gulf and in London knew well in advance that the delegation was arriving. However, changes in the size of the party were not communicated in time, and managers at prominent hotels in London 'utterly refused to accept Arab guests' because of problems they had encountered in the past, according to one account. No wonder, then, that Ahmad was feeling sour shortly after his arrival, and that he had asked to cut the trip short, hoping to return to Kuwait after his audience with the King Emperor. Fortunately, officials convinced Ahmad to continue on the itinerary, and he enjoyed the rest of his UK sojourn.