eReading Karma in Snakes and Ladders: two South Asian game boards in the British Library collections

This guest blog post is by Souvik Mukherjee, an Assistant Professor and Head of the Department of English at Presidency University in Kolkata. His research looks at the narrative and the literary through the emerging discourse of videogames as storytelling media and at how these games inform and challenge our conceptions of narratives, identity and culture.

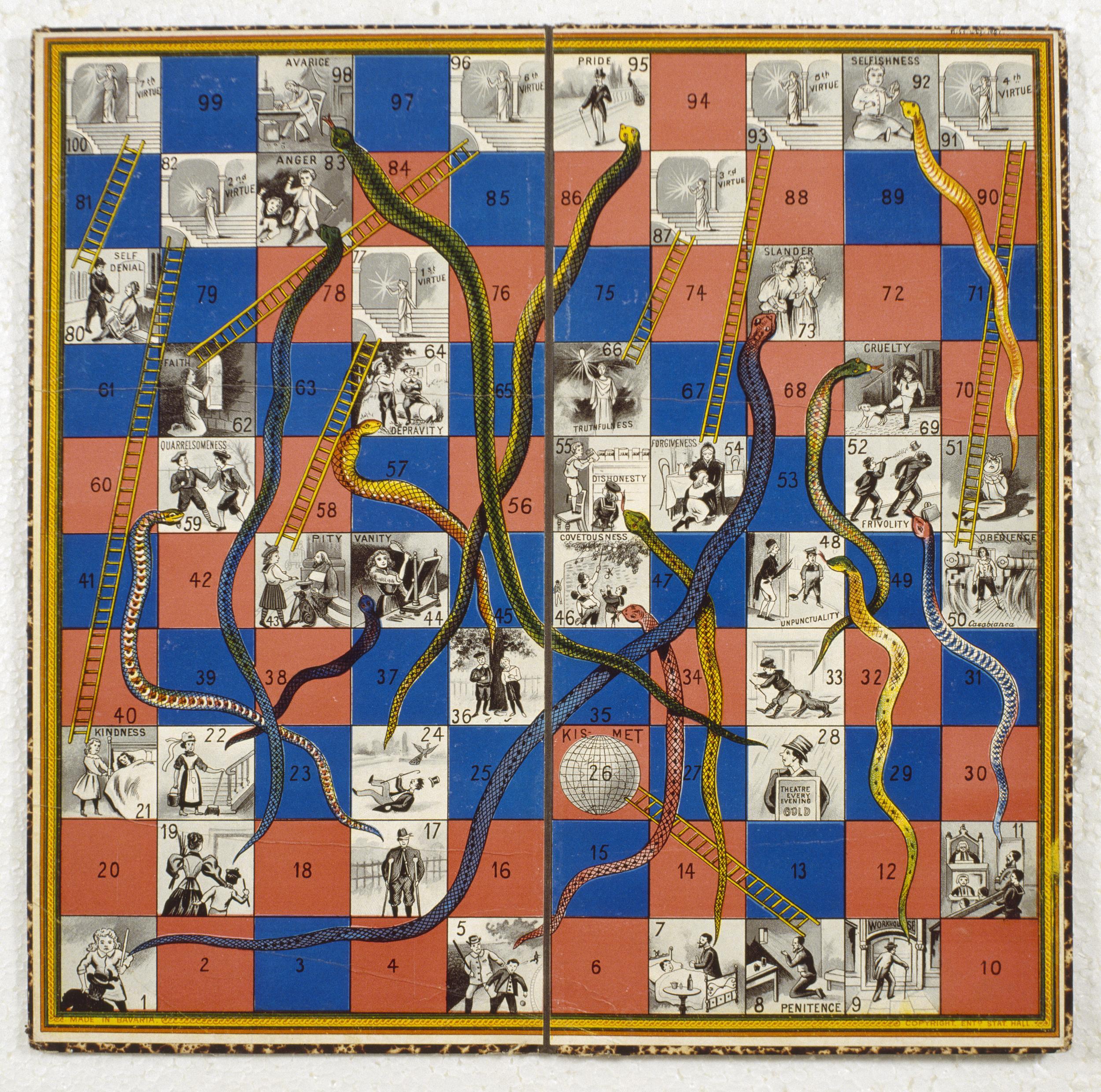

Salman Rushdie, in his novel, Midnight’s Children, writes about the game of Snakes and Ladders that ‘all games have morals; and the game of Snakes and Ladders captures, as no other activity can hope to do, the eternal truth that for every ladder you climb, a snake is waiting just around the corner; and for every snake, a ladder will compensate’ (Rushdie 2016, 160). Whether Rushdie is aware one does not know but Snakes and Ladders indeed has its beginnings as a game of morals, or even more than that – a game about life and karma. When Frederick Henry Ayres, the famous toymaker from Aldgate, London, patented the game in 1892, the squares of the game-board had lost their moral connotations. There were earlier examples in Victorian England and mainland Europe that had a very Christian morality encoded into the boards but the game actually originated in India as Gyan Chaupar (it had other local variations such as Moksha Pat, Paramapada Sopanam and other adaptations such as the Bengali Golok Dham and the Tibetan Sa nam lam sha). Victorian versions of the game include the Kismet boardgame (c.a. 1895) now in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s collection (fig. 1). There were other similar games such as Virtue Rewarded and Vice Punished (1818) and the New Game of Human Life (1790) although the latter did not contain snakes and ladders on its board.

Fig. 1. Kismet, c.1895. Chromolithograph on paper and card. Designed in England, manufactured in Bavaria. Victoria & Albert Museum, MISC.423-1981. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In the Indian versions, it was not a racing-game as it became in its Western adaptations. It was a game that did not end in square hundred but one that people could play over and over until they reached Vaikuntha (the sacred domain of Vishnu) after journeying though many rebirths and corresponding human experiences. Every square in the game signified a moral action, a celestial location or a state of being all of which were important in the Karmic journey. Here is the story of two game-boards in the British Library’s archives and how an Indian game designed to teach the workings of Karma and religion became the Snakes and Ladders that children play the world over, today.

One of the oldest Gyan Chaupar boards that have been traced so far is now in the British Library (Topsfield 1985, 203-226), originally in the collection of the East India Company officer Richard Johnson (1753-1807) (fig. 2). There are claims that the game originated much earlier – in the Kridakaushalya section of his 1871 Sanskrit magnum opus Brihad Jyotish Arnava, Venkatarama Harikrishna of Aurangabad states that the game was invented by the Marathi saint Dnyaneshwar (1275 – 1296). Andrew Topsfield lists around forty-four game-boards in his two articles published two decades apart and these boards belong to multiple religious traditions, Hindu, Jain and Muslim (Sufi). Topsfield mentions older boards that date back to the late 15th century and also ones that have 128 squares, 84 squares or a 100 squares instead of the 72 squares as on the Johnson board. There is, however, another board in the British Library that has probably not been written about yet. Listed as the Paramapada Sopanam Pata (fig. 3), it is described in the catalogue as: ‘Lithograph in Blockwood printing. of the game Paramapada sōpānam, a traditional Indian indoor game: in a chart titled: Paramapada Sopanam, in which the highest ascent indicates reaching Heaven and anywhere else where the pawn lands indicate various worlds according to Hindu mythology. Language note: In Kannada and Devanagari’. These two boards tell the story of the transculturation of a game that started out as a pedagogical tool to teach the ways of karma and ended up as Hasbro Inc.’s Chutes and Ladders.

Designs for a game of snakes and ladders, gyan chaupur, commissioned by Richard Johnson, Lucknow, 1780-82. Johnson Album 5,8.

Paramapada Sopanam Pata, board game printed in Karnataka, c. 1800-1850. British Library, ORB 40/1046.

Around 1832, a Captain Henry Dundas Robertson would present what he called the Shastree’s Game of Heaven and Hell to the Royal Asiatic Society in London where the 128-square Vaishnav Gyan Chaupar board can still be seen. Around 1895, when the game was being sold in England as a children’s game, the civil servant Gerald Robert Dampier was sending a detailed report on the game to North Indian Notes and Queries. Around a century before Dampier and fifty years before Robertson, Richard Johnson’s possession of a Gyan Chaupar board around 1780-2 is in itself a curious affair. This board is now part of the British Library’s collection. Johnson, the deputy resident at Lucknow, is among the lesser-known Orientalists despite his prodigious collection of Indian art and his close connection with orientalists of greater repute such as Sir William Jones. Johnson was supposedly a competent official but he made a fortune through corruption and was called ‘Rupee Johnson’; he was also involved in Warren Hastings’s infamous looting of the Begums of Oudh. In his two years in Oudh (1780-82) Johnson was, however, seems to have been popular and was given the title Mumtāz al-Dawlah Mufakhkhar al-Mulk Richārd Jānsan Bahādur Ḥusām Jang, 1194 or ʻRichard Johnson chosen of the dynasty, exalted of the kingdom, sharp blade in war’, 1780 together with a mansab and an insignia by the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam. Johnson was also an eclectic collector and commissioned work by many Indian artists and scholars of which 64 albums of paintings (over 1,000 individual items) and an estimated 1000 manuscripts in Persian, Arabic, Turkish, Urdu, Sanskrit, Bengali, Panjabi, Hindi and Assamese form the ‘backbone of the East India Company library’ (now at the British Library, see Sims-Williams 2014). While other orientalists such as Jones and Hiram Cox wrote on Chess, Johnson seems to have been interested in other games. Besides the Gyan Chaupar board, the Johnson collection contains the Persian game of Ganj (Treasure) and sketches for Ganjifa cards – the round playing cards that were common in India before the advent of European cards (British Library, Johnson Album 5).

Johnson’s contribution to boardgame studies is no less important than that of the other orientalists although it has taken over two centuries to appreciate this. The Gyan Chaupar board was in his possession a good century before the game was imported to the West and transformed into a race-game. Johnson seems to have been interested in the original game and besides the Devanagari script, each square also contains a farsi transliteration. The words are not Persian but the script is.[i] It is difficult to identify the painter or the source – Malini Roy points out that ‘artists affiliated with Johnson’s studio include Mohan Singh, Ghulam Reza, Gobind Singh, Muhammad Ashiq, Udwat Singh, Sital Das, and Ram Sahai’ (Roy 2010, 181). Whether Johnson read the game-board is a moot question but he certainly cared to get the words transliterated into Persian. Beginning the game on utpatti or ‘origin’, the player can move to maya or ‘illusion’ (square 2), krodh or lobh – ‘anger’ and ‘greed’ respectively (squares 3 and 4) and ascend higher towards salvation via the ladders in the squares that represent daya or mercy (square 13) or Bhakti or devotion (square 54). Bhakti will take the player directly to Vaikuntha and salvation from the cycle of rebirths and the game ends here. For a game purportedly invented by a major figure of the Bhakti Movement, this is no surprise. If the throw of the dice takes the player beyond square 68, then the long snake on square 72 brings the player back to Earth and the cycle of rebirths continues. Johnson’s board is unique among the Gyan Chaupar boards that are known to scholars in that it contains two scorpions in addition to the snakes and the ladders also look somewhat serpentine.

One more detail is not obvious from the board. None of these boards comes with playing pieces or dice but writing in 1895, Dampier claims that the game was played with cowrie shells as dice and he also adds that the game is ‘very contrary to our Western teachings […] it is not clear why Love of Violence (sq. 72) should lead to Darkness (sq. 51)’. Dampier notes that the game has been ‘lately introduced in England and with ordinary dice for cowries and [with] a somewhere revised set of rules been patented there as a children’s game’ (Dampier 1895, 25-27).

Dampier’s short but detailed account of Gyan Chaupar provides a clearer entry point into how and why an ‘oriental’ game of karma needed to be Westernised as a children’s game. The transition from the karmic game to the game on Christian morality and then to a race-game for children embodying competition rather than soul-searching is evident from his pithy notes sent to the journal North Indian Notes and Queries. One might assume that the principles working here would have been very different from Johnson’s approach to the game. The story, nevertheless, does not end here. I was fortunate to discover another game-board in the British Library as I mention above. The Paramapada Sopanam or the Ladder to Heaven is similar to the Johnson board in most ways except that there are only snakes on the board. Some snakes help the player ascend and the others are for descent (I purposely eschew terms like ‘good’ and ‘bad’ here). Square 54 or Bhakti, a many-headed serpent leads the player to Vaikuntha (the board is damaged here) and one might assume that it is Ananta, the celestial snake on which Vishnu reclines. There are some differences with the Johnson board although both relate to the Vaishnav sect of Hinduism. While Gyan Chaupar is largely forgotten in Northern India (except in the Jain tradition where it is reportedly played by some during the Jain festival Paryushan), Paramapada Sopanam is regularly played on the festive day of Vaikuntha Ekadasi in the Indian states of Telengana, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. In fact, Carl Gustav Jung supposedly obtained a copy of the game when he visited Tamil Nadu in 1938 and took it back to Zurich; Sulagna Sengupta concludes that Jung read the matrix of the game as the play of opposites in the psyche (Sengupta 2017).

From the karmic game to Jung’s model for the play of psychological opposites, Gyan Chaupar in its many forms is certainly much more than the race game that it has been changed into after its appropriation by the colonial apparatus. Recent research has been able to identify many of these game-boards and these two boards in the British Library are crucial for the ‘recovery research’ into Gyan Chaupar and its variants as well as the cultures in which they were conceived. Recent research on games talks of ‘gamification’ or the application of ludic principles to real-life activities – a closer look at the original Gyan Chaupar will show its merit as a gamified text, an instructional manual on the ways of life and on Indic soteriology.

Notes

[i] I am indebted to Ms Azadeh Mazlousaki Isaksen of the University of Tromso, Norway, for the translations. Ms Isaksen initially struggled to translate the words as she found them unfamiliar. The reason was that these were Hindi or Sanskrit words written in the Persian script.

Bibliography

Cannon, Garland, and Andrew Grout. “Notes and Communications.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, vol. 55, no. 2, 1992, pp. 316–318.

Dampier, Gerald Roberts. “A Primitive Game.” North Indian Notes and Queries V (1895): p. 25-27.

Roy, Malini. “Origins of the Late Mughal Painting Tradition in Awadh.” India’s Fabled City: The Art of Courtly Lucknow. Ed. Stephen Markel and Tushara Bindu Gude. Los Angeles: Prestel, 2010.

Rushdie, Salman. Midnights Children. London: Random House, 2016.

Sengupta, Sulagna. “Parama Pada Sopanam : The Divine Game of Rebirth and Renewal.” Jungian Perspectives on Rebirth and Renewal: Phoenix Rising. Ed. Elizabeth Brodersen and Michael Glock. London ; New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2017.

Sims-Williams, Ursula. “‘White Mughal’ Richard Johnson and Mir Qamar al-Din Minnat.” British Library Asian and African Studies Blog, 1 May 2014.

Topsfield, Andrew. “The Indian Game of Snakes and Ladders.” Artibus Asiae, vol. 46, no. 3, 1985, pp. 203–226.

By Dr. Souvik Mukherjee