The riverfront at Agra once formed one of the great sights of Mughal India. In addition to the great fort rebuilt by the Emperor Akbar (r. 1556-1605) and the Taj Mahal (the tomb built for the Emperor Shah Jahan’s wife Mumtaz Mahal, d.1633), both banks of the River Yamuna were lined with great mansions, palatial garden houses, grand tombs and imperial gardens. The houses of the princes and mansabdars lined the right bank up- and down-river from the fort, while the left bank was mostly devoted to imperial gardens. The Emperor Babur (r. 1526-30) had been the first to build a garden at Agra, nearly opposite the site of the Taj Mahal, and other imperial gardens were laid out on the left bank of the river mostly in the time of the Emperors Jahangir (r.1605-27) and Shah Jahan (r.1628-58). Jahangir and Shah Jahan gave the land on the riverbanks to their sons and to the great nobles of the empire. Jahangir’s powerful Iranian wife Nur Jahan laid out the garden now known as the Ram Bagh and also converted the garden of her parents, I`timad al-Daula and his wife ‘Asmat Banu Begum, into the first of the great tombs in Agra itself, while Mumtaz Mahal herself began the garden that was finished by her daughter Jahanara. Apart from the emperor and the imperial women, all the men who built gardens or tombs on the river front were mansabdars (high-ranking officers of the court).

Land could be bought, but the prestigious riverfront sites were granted to the nobles by the emperor and could be reclaimed after their death. The best way for a Mughal mansabdar to ensure that his mansion or land was not reclaimed was to build his tomb on it, when it became inviolable. Several of the garden houses were therefore converted into tomb gardens. After Shah Jahan moved the capital to Delhi in 1648, Agra declined and its gardens and buildings became of less importance to the emperor, so that most of those houses and gardens remaining are still generally known by their last Shahjahani owner.

Apart from the Taj Mahal and the fort, only the gardens and tombs of the upper left bank of the river round the tomb of I`timad al-Daula survive today in anything like the state in which their former splendour can be appreciated. The city was repeatedly sacked in the eighteenth century by Afghan invaders as well as more local marauders in the form of Jats, Rohillas and Marathas, until it came into the possession of the East India Company in 1803. A thorough study of the riverfront at Agra was made by Ebba Koch in her book on the Taj Mahal published in 2006. The evidence there presented can now be supplemented by an important panoramic scroll of the riverfront at Agra acquired recently by the British Library (Or.16805). This painted and inscribed scroll shows the elevations of all the buildings along both sides of the river as it flows through the whole length of the city. The length of the scroll is 763 cm and the width 32 cm. A full description of the scroll can be found in Ebba Koch’s and the present writer’s joint article in the eBLJ (9 of 2017).

The scroll is drawn in a way consistent with the development of Indian topographical mapping. The river is simply a blank straight path in the middle of the scroll, its great bend totally ignored, while the buildings and gardens on either side are rendered in elevation strung out along a straight base line. Buildings and inscriptions on each side of the river are therefore upside down compared to those on the opposite side. Inscriptions in English and Urdu are written above each building, two of which enable the scroll to be approximately dated. ‘Major Taylor's garden’ is noted near the Taj Mahal. This is Joseph Taylor of the Bengal Engineers who worked at Agra on and off from 1809 until his death in 1835. His rank was that of a Major between 1827 and 1831. He had lived with his family in the imperial apartments in the fort (this was no longer allowed by 1831) and also had fitted up a suite of rooms at the Taj Mahal between the mihman khana (the assembly hall for imperial visits on the east side of the tomb itself) and the adjacent river tower. This piece of evidence is however contradicted by the absence on the riverbank north of the fort of the Great Gun of Agra, which was depicted in all panoramic views of the fort from the river, until it was blown up for its scrap value in 1833 (see the present author’s essay on the Great Gun in the BLJ in 1989). At the moment it seems best to date the scroll to c. 1830. It must be stressed, however, that the artist was not necessarily sketching all the monuments afresh, but could rather as with most Indian artists be relying on earlier versions of the same subject for some of them. A key discrepancy for instance arises in Ja`far Khan’s tomb, which is much better preserved in the scroll than in a drawing in Florentia Sale’s notebook also from c. 1830 (MSS Eur B360(a), no. 43).

The garden of I`tiqad Khan and the tomb of Ja’far Khan, Agra artist, c. 1830 (Or. 16805, detail)

The scroll reveals the tomb for the first time as a double-storeyed structure, much resembling that of Ja’far Khan’s grandfather I’timad al-Daula across the river, built by his daughter Nur Jahan whom Jahangir had married in 1611, thereby propelling her family to the most important positions in the empire. An important new finding from the scroll is the evidence of the concentration of the upper right bank of the Yamuna of structures connected with the family of Nur Jahan. Just upriver from Ja’far Khan’s tomb were the gardens of Nur Jahan’s brother and sister I`tiqad Khan (d. 1650) and Manija Begum,. Ja`far Khan (d. 1670) was the son of another of Nur Jahan’s sisters and was married to his cousin Farzana Begum, Asaf Khan’s daughter and the sister of Mumtaz Mahal. He was thus the son-in-law as well as the nephew of Jahangir’s vizier powerful Asaf Khan and also Shah Jahan’s brother-in-law. His mansion was downstream nearer the Fort as was that of his uncle Asaf Khan, next to the mansions of the imperial princes.

The Agra Fort, Agra artist, c. 1830 (Or. 16805, detail)

Downstream from the Fort were the mansions of some of the great officers of state of Jahangir and Shah Jahan – Islam Khan Mashhadi, A’zam Khan, who was son-in-law to Asaf Khan, Mahabat Khan (Jahangir’s thuggish general), Raja Man Singh of Amber (who owned land in Agra including the site of the Taj Mahal, exchanged with Shah Jahan for four other mansions in Agra), and Khan ‘Alam, Jahangir’s ambassador to Shah ‘Abbas I of Iran, who retired early in the reign of Shah Jahan to his garden in Agra on account of his old age and his addiction to opium. His mansion was next to the tomb of Mumtaz Mahal.

Khan ‘Alam’s mansion and garden, Agra artist, c. 1830 (Or. 16805, detail)

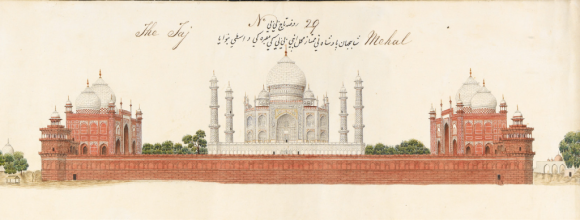

The Taj Mahal, with part of Major Taylor’s garden on the left, Agra artist, c. 1830 (Or. 16805, detail)

After the Taj Mahal came the garden established by Major Taylor and then the mansion of Khan Dauran.

The mansion of Khan Dauran and Major Taylor's Garden, Agra artist, c. 1830 (Or. 16805, detail)

We now cross the river and proceed back upstream. The gardens and monuments on the left or eastern bank on the scroll are numbered in the reverse direction to those on the opposite bank. On this side there are fewer mansions and more gardens, most of them former imperial gardens.

The Mahtab Bagh, Agra artist, c. 1830 (Or. 16805, detail)

Our anonymous scribe continues the mistaken tradition that Shah Jahan had the Mahtab Bagh or Moonlight Garden laid out opposite the Taj Mahal (‘Emperor Shah Jahan had it built as his grave’) so that he could be buried there. In fact it was laid out by the emperor as a char bagh garden (divided by paths and canals into four) for viewing the mausoleum of Mumtaz Mahal on the opposite bank. An octagonal pool reflected the Taj Mahal in its waters and this was immediately in front of the bangla pavilion depicted here.

The left bank was largely occupied by imperial gardens with few structures surviving until much further upstream with the tomb of I’timad al-Daula, Jahangir’s vizier, and his wife. After his vizier’s death in 1622, shortly after that of his wife, Jahangir gave his property to Nur Jahan and she (and not her father as erroneously claimed in the inscription) was therefore able to build this tomb for her parents in his garden on the bank of the Yamuna (all the property of deceased mansabdars normally reverted to the state on their death). Just upriver is the domed tomb of Sultan Pariviz, Jahangir’s second son, whose excessive indulgence in alcohol resulted in his death in 1626.

Tomb of I’timad al-Daula and Sultan Parviz’s tomb, Agra artist, c. 1830 (Or. 16805, detail)

Upriver is the tomb of Wazir Khan. Hakim ‘Alim al-Din titled Wazir Khan was one of the most esteemed nobles of the reign of Shah Jahan. He was governor of the Punjab 1631-41 and renowned for his patronage of architecture in Lahore, where his comparatively long governorship enabled him to build a famous mosque and a hamman or baths. Only the two corner towers of his garden in Agra survive, the central pavilion and its tahkhana being now ruinous, and the rest of the garden has been built over.

Garden of Wazir Khan and tomb of Afzal Khan (the ‘China tomb’), Agra artist, c. 1830 (Or. 16805, detail)

Alongside Wazir Khan’s tomb is that of Afzal Khan Shirazi, who was divan-i kul or finance minister under Shah Jahan. He died in 1639 at Lahore and his body was brought back to Agra to be buried in the tomb he had built in his lifetime. It is decorated outside with the coloured tiles which were a speciality of Lahore, as found on the walls of the Lahore fort and of the mosque of Wazir Khan, and with painted decorations inside. The tomb survives but its original decoration is largely gone and the interior has been repainted.

Jahanara’s garden and Nur Jahan’s garden, the Rambagh, Agra artist, c. 1830 (Or. 16805, detail)

Jahanara (1614-81) was the eldest child as well as the eldest daughter of Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal, and she held a special place in her father’s affections after the death of her mother in 1631, when she became the Begum Sahiba and ran the emperor’s household. Her garden was one of the largest on the Agra riverfront. It was in fact begun by her mother during Jahangir’s reign and is the only foundation which can be connected to the patronage of the Lady of the Taj. The earlier construction phase can be seen in the uncusped arches of the lower two storeys of the corner towers, to which Jahanara added smaller chhatris. Only one of them survives and the large pavilion fronting the river has now gone, so that the scroll’s evidence is of the greatest importance in showing the details of the riverside elevation.

Next door to Jahanara’s garden is Nur Jahan’s garden, now known as the Rambagh. She seems to have laid out this garden shortly after her wedding to Jahangir in 1611 and it is the earliest surviving Mughal garden in Agra. It was named the Bagh-i Nur Afshan, the name Ram Bagh by which it is popularly known being a corruption of its later denomination Aram Bagh. Two pavilions end on to the river, each consisting of alternate open verandas and enclosed rooms, face each other across a pool on an elevated terrace, with a tahkhana beneath. The garden was never meant to be symmetrical, unlike later Mughal ones, and the pavilions occupy the southern end of the elevated terrace by the river.

From this unique scroll we learn that despite the ravages of time, neglect and war, in 1830 there was still considerable evidence of Agra’s imperial past to be seen along the riverfronts. Many towers and facades remained along with a considerable number of mansabdari and princely mansions albeit partly ruinous. After the Uprising of 1858, the picture changes dramatically. As in Delhi, whole swathes of the city near the fort were demolished to afford a clear field of fire and the remains of all the nearby mansions were blown up. Roads were laid out along the right bank punching through the gardens that were left. Bridges were constructed across the Yamuna for rail and road that destroyed the environment at either end. Only a few of the imperial gardens at the northern end of the left bank survived in any form, while the rest were converted into fields for crops and are now being built over for Agra’s expanding population. It is now 400 years since the heyday of Agra as an imperial capital and our scroll, suspended half way between then and now, affords us a precious glimpse of how it once was.

Further reading:

Koch, Ebba, The Complete Taj Mahal, London, 2006

Koch, E., and Losty, J.P., ‘The Riverside Mansions and Tombs of Agra: New Evidence from a Panoramic Scroll recently acquired by the British Library’, in eBLJ, 2017/9

Losty, J.P., ‘The Great Gun at Agra’, British Library Journal, xv (1989), pp. 35-58

J.P. Losty (Curator Emeritus, Visual Arts Collection)