Presentation of royal identity in medieval books is rarely as straightforward as it may appear. One of the aims of our exhibition Royal Manuscripts: The Genius of Illumination is to explore the ways royal identity was both articulated and shaped by the medieval manuscripts that propagated royal genealogies, customs and tastes.

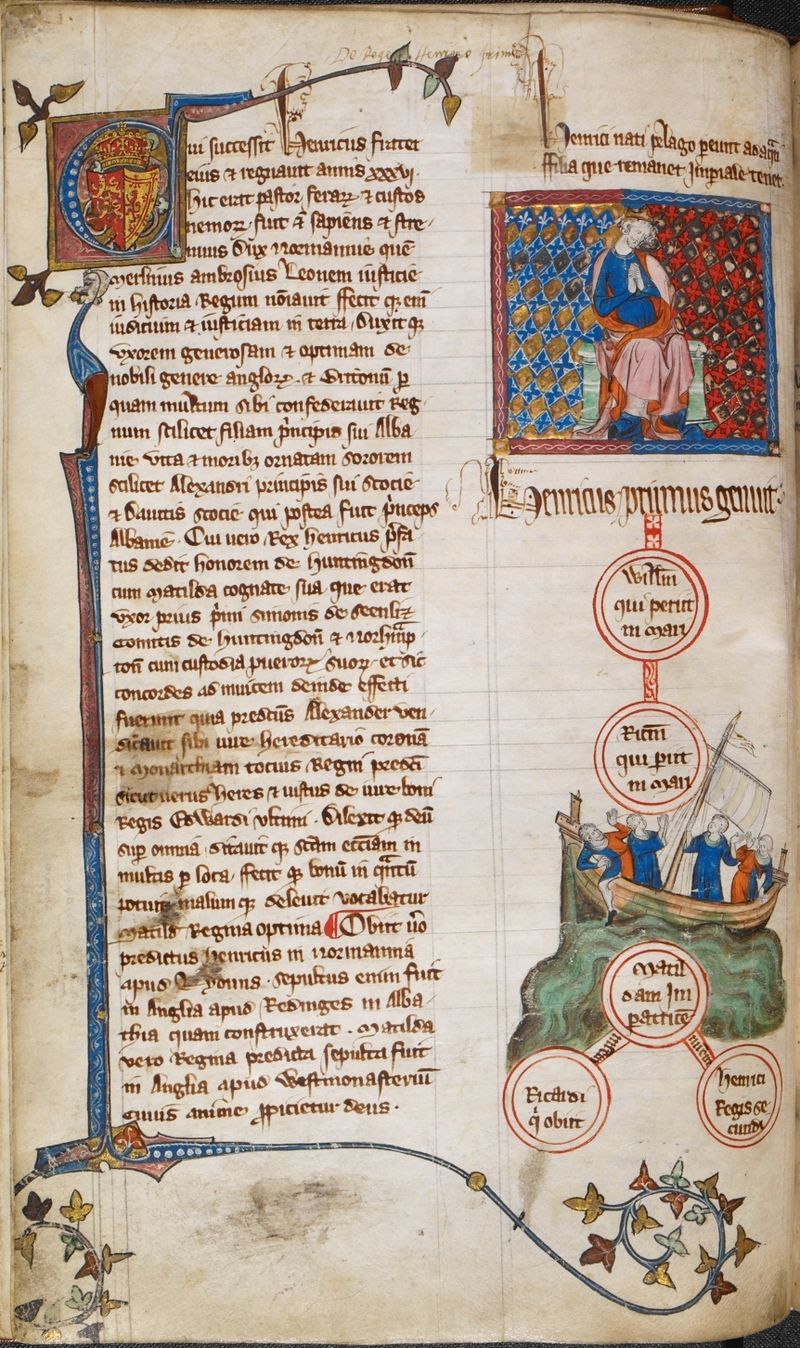

Henry I and his descendants, Cotton Claudius D. ii, f. 45v.

Henry I and his descendants, Cotton Claudius D. ii, f. 45v.

The Book of the Laws of Ancient Kings (Liber legum antiquorum regum; Cotton Claudius D. ii), a handsomely illuminated volume featured in the exhibition, was not made for presentation to a monarch. A compilation of royal statutes and London ordinances, this manuscript, shown above, was produced in London, c. 1321, for the use of the Guildhall of London, where it remained until the sixteenth century.

Detail of the miniature of Henry I, Cotton Claudius D. ii, f. 45v.

Detail of the miniature of Henry I, Cotton Claudius D. ii, f. 45v.

As is fitting for a book destined for Guildhall, many texts within this manuscript focus on London and its civic liberties. It also, however, contains potent representations of royal authority in connection with laws promulgated under a succession of Anglo-Saxon and Norman kings of England. Portraits of these kings, like the one of Henry I shown above, precede the charters and laws set forth during their respective reigns.

These portraits are placed in dynastic and lineal context through the genealogical diagrams that accompany them. Thus, this portrait of Henry I is followed by roundels naming his sons, daughter and the grandchild, Henry, who would eventually reign as Henry II. The laws underpinning civic life and order are represented here as inextricable from the succession of rulers by whose authority the laws were proclaimed and upheld.

Detail of the wreck of the White Ship, Cotton Claudius D. ii, f. 45v.

Detail of the wreck of the White Ship, Cotton Claudius D. ii, f. 45v.

This royal authority over law is promoted in the portrait of Henry I, but the genealogical diagram beneath this miniature contains an image, shown above, alluding to a traumatic rupture in his royal line and to an attendant rupture in the land. In 1120, Henry I (r. 1100-1135) had finally solidified royal control of the duchy of Normandy after years of fighting with the French. In the previous year, the marriage of his sole legitimate male heir, William Ætheling, to Matilda of Anjou had brought the desirable county of Maine into English hands as well. The seventeen year old prince was thus securely positioned to rule England, Normandy and Maine after his father’s death.

King Henry’s careful grooming of his son for rule all came to naught on 25 November 1120, when father and son set sail from Normandy for England. Henry had initially been offered a new ship, called the White Ship, in which to make the trip, but he chose to sail in another ship, leaving the White Ship for the Ætheling and his youthful aristocratic entourage (including some of his many illegitimate half-siblings). The White Ship set off from Barfleur in the evening. By the time of its departure the young passengers and crew had been celebrating and many were said to have been quite inebriated as the ship set sail. According to one contemporary chronicler, the intoxicated sailors imprudently sought to overtake the king's ship, knowing that theirs was the newer and swifter of the two. It was not long before the ship’s pilot carelessly allowed the ship to be rowed into an underwater rock just outside the harbour at Barfleur. The image below, from another early fourteenth-century manuscript featured in the exhibition, shows a more violent depiction of the destruction that followed.

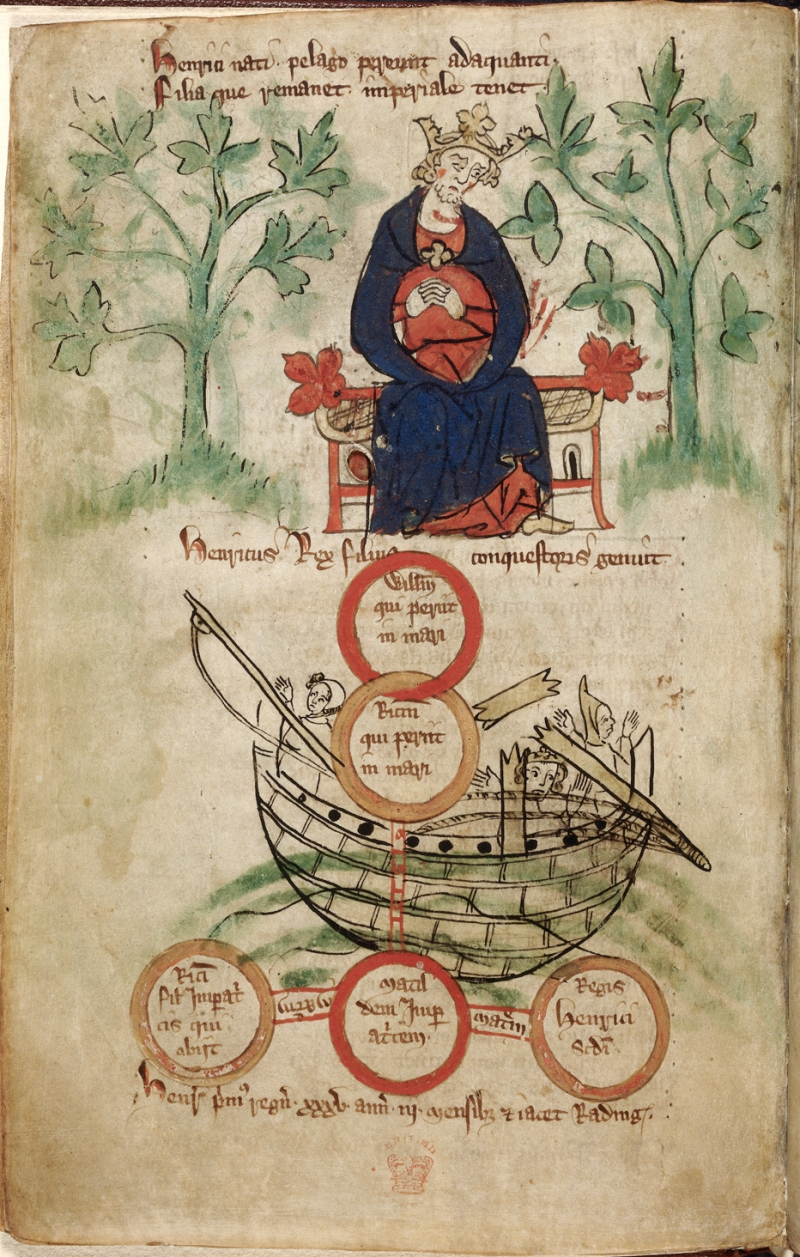

King Henry I and the White Ship in a series of images of English kings preceding Peter of Langtoft’s Chronicle, Royal 20 A. ii, f. 6v.

King Henry I and the White Ship in a series of images of English kings preceding Peter of Langtoft’s Chronicle, Royal 20 A. ii, f. 6v.

The only survivor of the shipwreck, it is said, was a butcher of Rouen. William Ætheling was drowned, as was Richard, King Henry’s natural son, and Matilda of Perche, Henry’s natural daughter. The tragic deaths of Henry’s sons are recorded in the genealogical roundels above the White Ship: ‘Willelmum qui periit in mari’ and ‘Ricardum qui periit in mari’. The roundel directly beneath the White Ship contains the name of Henry’s surviving legitimate child, Matilda, widow of the Holy Roman Emperor Henry V (‘Matildam imperatricem’).

When Henry failed to beget a new male heir after the White Ship tragedy, he named Matilda as his heir and had his court swear to support her as monarch after his death. One of the first to swear was Stephen of Blois, who moved swiftly to secure his own election to kingship after Henry’s death, thereby instigating a period of protracted civil war and lawlessness in England. This war would eventually end with the naming of Henry II, Matilda’s son and England’s first Plantagenet monarch, as Stephen’s heir, but the catastrophic death of William Ætheling and his young comrades undoubtedly had a profound and lasting effect on English history. The depiction of the event in a fourteenth-century book of legal statutes attests to medieval recognition of the import and consequences of the tragic wreck of the White Ship.

- Royal project team