The most beautiful Arthurian manuscript from the Royal collection, recently displayed in our exhibition, Royal Manuscripts: The Genius of Illumination, is now online on our Digitised Manuscripts site (click here for the fully digitised version of Royal 14 E. iii, and the entry in the Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts).

Detail of a miniature of Sir Galahad and his companions on the Quest for the Holy Grail, approaching a castle which is destroyed by lightning (Part 2, Queste del Saint Graal): France, N. (Saint-Omer or Tournai?), c. 1315-1325 (London, British Library, MS Royal 14 E. iii, f. 133v).

Detail of a miniature of Sir Galahad and his companions on the Quest for the Holy Grail, approaching a castle which is destroyed by lightning (Part 2, Queste del Saint Graal): France, N. (Saint-Omer or Tournai?), c. 1315-1325 (London, British Library, MS Royal 14 E. iii, f. 133v).

All the manuscript's vibrant borders and its 116 gilded images can be viewed ‘up-close and personal’ on Digitised Manuscripts. The French text, written in a fine 14th-century Gothic bookscript, includes those parts of the Lancelot-Grail epic with predominantly Christian themes – the Holy Grail legend and the destruction of Arthur’s court by a combination of human frailty and evil. The more frivolous adventures of Lancelot and the story of Merlin are not included.

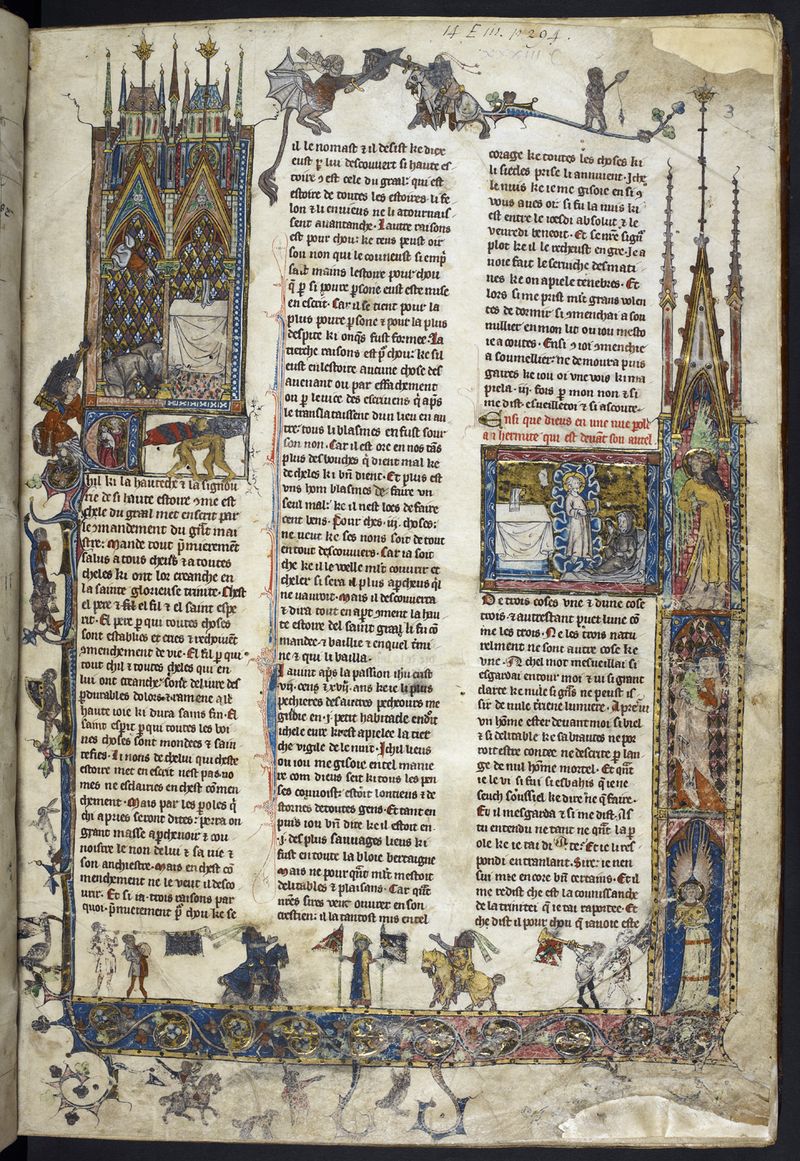

Royal 14 E. iii is a very large book, almost half a metre tall, with three columns of writing per page. It was produced in a workshop in the Franco-Flemish border region, possibly in Tournai or Saint-Omer, for an unknown aristocratic patron. The text and images are designed not only to educate the reader in chivalric and Christian values, but to make the lessons entertaining. The first page is dominated by two religious images with a backdrop of altars and spires. But a closer look at the borders reveals all manner of strange beings involved in a variety of distinctly non-religious activities: a knight jousting with a hybrid creature with a human head, dragon’s wings, hooves and a tail; two strange hairy creatures in capes locked in some kind of embrace; and rabbits and musicians capering along the edges of the text.

Miniature of the author as a hermit prostrating himself before the altar with a chalice, the Manus Dei blessing him, a historiated initial 'C'(hil) of a young man with a dog, at the beginning of the text, and a miniature of a hermit speaking with God, following the rubric, 'Ensi que dieus eu une nue parole an hermite qui est devant son autel'; with a partial border containing two angels and the Virgin with Child, a tournament scene with knights and musicians, a hunting scene, animals and hybrids (Part 1: Estoire del Saint Graal): France, N. (Saint-Omer or Tournai?), c. 1315-1325 (London, British Library, MS Royal 14 E. iii, f. 3r).

Miniature of the author as a hermit prostrating himself before the altar with a chalice, the Manus Dei blessing him, a historiated initial 'C'(hil) of a young man with a dog, at the beginning of the text, and a miniature of a hermit speaking with God, following the rubric, 'Ensi que dieus eu une nue parole an hermite qui est devant son autel'; with a partial border containing two angels and the Virgin with Child, a tournament scene with knights and musicians, a hunting scene, animals and hybrids (Part 1: Estoire del Saint Graal): France, N. (Saint-Omer or Tournai?), c. 1315-1325 (London, British Library, MS Royal 14 E. iii, f. 3r).

Anyone who has attempted to read the entire Lancelot-Grail epic with its complex structure of interwoven episodes will be able to sympathise with the medieval audience who needed light relief from time to time!

The three parts of the Lancelot-Grail legend in this manuscript are:

Estoire del Saint Graal (The Story of the Holy Grail): the chalice in which Joseph of Arimathea collected Christ’s blood, how it was brought to England by his descendants, and the origin of the Round Table.

Detail of a miniature of Joseph of Arimathea on his deathbed, entrusting the Grail to Alain, (Part 1: Estoire del Saint Graal): France, N. (Saint-Omer or Tournai?), c. 1315-1325 (London, British Library, MS Royal 14 E. iii, f. 86r).

Detail of a miniature of Joseph of Arimathea on his deathbed, entrusting the Grail to Alain, (Part 1: Estoire del Saint Graal): France, N. (Saint-Omer or Tournai?), c. 1315-1325 (London, British Library, MS Royal 14 E. iii, f. 86r).

Queste del Saint Graal (The Quest for the Holy Grail): the adventures of Perceval, Galahad and the knights of the Round Table as they seek the Holy Grail. The quest is completed by Galahad, the purest knight, son of Lancelot.

Mort Artu (The Death of Arthur): this part tells of Lancelot’s love for Guinevere and his willingness to risk everything in her defence. This manuscript breaks off just as the armies of Lancelot and King Arthur are preparing for the final battle, which will result in Arthur’s death and the destruction of the court at Camelot.

Detail of a miniature of Sir Lancelot fighting Sir Mados to defend the honour of Guinevere, watched by Arthur, Guinevere, and the court, France, N. (Saint-Omer or Tournai?), c. 1315-1325 (London, British Library, MS Royal 14 E. iii, f. 156v).

Detail of a miniature of Sir Lancelot fighting Sir Mados to defend the honour of Guinevere, watched by Arthur, Guinevere, and the court, France, N. (Saint-Omer or Tournai?), c. 1315-1325 (London, British Library, MS Royal 14 E. iii, f. 156v).

For information on other Arthurian manuscripts held in the British Library collections, including a full set of the entire Lancelot-Grail legend produced in the same workshop as this one (Additional MSS 10292, 10293 and 10294), see the Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts and associated virtual exhibition.

Royal 20 D. iv, another exceptional manuscript from the Royal collection, also containing the Lancelot du Lac, will be digitised later this year.

- Chantry Westwell