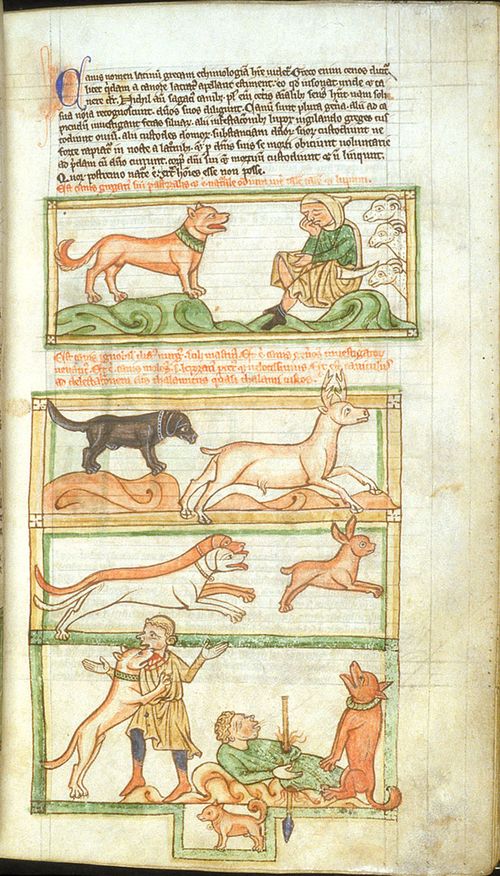

Detail of a miniature of King Garamantes, being rescued by his dogs; from the Rochester Bestiary, England (Rochester?), c. 1230, Royal MS 12 F. xiii, f. 30v

Recently we examined cats in medieval manuscripts. But what about man's best friend, the

dog? Dogs were, then as now, renowned for

their loyalty. Medieval tomb effigies

sometimes included a dog resting at the feat of the deceased, indicating the loyalty of the dead man himself, a faithful retainer to his

lord.

Miniatures of a sheepdog, a hunting dog in pursuit of a stag, a hunting dog in pursuit of a hare, and (bottom) the story of the dog mourning by the body of his murdered master and identifying the killer; from a bestiary, England, 2nd or 3rd quarter of the 13th century (after 1236), Harley MS 3244, f. 45r

This quality of loyalty works its way into many of the

stories told about dogs in bestiaries. A

king named Garamantes was once captured by his enemies. He was freed, however, when his hundreds of

dogs spontaneously charged, attacking the men who held him prisoner, and

leading him back to safety. In another

story, a man was murdered by his enemy.

His faithful dog was inconsolable, and stood beside the corpse, howling

and drawing a crowd of onlookers. When the

murderer saw this crowd gathering, he thought to allay suspicion by mingling

with the throng. But the dog was not

fooled. He attacked the murderer, biting

him and continuing to howl in mourning.

Faced with such a clear accusation, the murderer confessed.

Detail of a miniature of Sir Lancelot, in conversation with a lady holding a small dog on her lap; from Morte Artu, France (St Omer or Tournai?), c. 1315-1325, Royal MS 14 E. iii, f. 146r

Dogs in medieval manuscripts are most often hunting hounds,

chasing down hares, or dogs fierce in defence of their masters. But lap dogs also appear in medieval texts:

small, aristocratic animals who were the companions of fashionable ladies. Sir Tristan, so the story goes, sailed to France, where

the king's daughter fell in love with him.

But Tristan was already in love with Isolde, the wife of his uncle King

Mark, and refused the princess's advances.

She sent to him love letters, though, as well as a small dog, named

Husdent. While the affair with the

French princess was one-sided and short-lived, Husdent himself would go on to

become an important part of Tristan's story.

Devastated that he could not be with the married Isolde, Tristan lost

his senses and ran into the forest to live as a wild man. On returning to civilization some time later,

he was so altered from his ordeal that Isolde did not recognize him. But the faithful Husdent immediately knew his

master, and Tristan's true identity was revealed.

Miniature of the personification of Gluttony, riding on the back of a wolf; from the Dunois Hours, France (Paris), c. 1440-c. 1450 (after 1436), Yates Thompson MS 3, f. 168v

Man's faithful companion also had a more wild and

threatening counterpart. If dogs were symbols of loyalty, wolves were

personifications of greed. Isidore of

Seville observed, correctly, that the Latin word for wolf (lupus) gave rise to a slang term for prostitute (lupa).

These women were said to be greedy for financial gain, and so were

termed 'she-wolves'.

A she-wolf from mythology: detail of a miniature of (foreground) two men digging a grave for the Rhea Silvia, the princess and Vestal Virgin sentenced to death for bearing Romulus and Remus, the twin sons of the god Mars, who are shown behind with the she-wolf (lupa) that raised them after their usurping great-uncle cast them out to die; from a French translation of Giovanni Boccacio, De claribus mulieribus, France (Rouen), c. 1440, Royal MS 16 G. v, f. 55r

Just as dogs were shown as helpful working animals, the

protectors of the flock, wolves were the greedy thieves who ran off with the

sheep. But a wolf needed to be careful

lest he be caught in the act, since he shared one of his cousin's major

weaknesses: dog breath. The smelly

breath of a wolf could, the bestiaries claimed, give him away as he crept up on

his prey, alerting the watching sheepdogs.

A canny wolf would plan for this, however, and always approach a flock

from downwind.

Detail of a miniature of a wolf, sneaking up on sheep from downwind; from a bestiary, England, c. 1200-c. 1210, Royal MS 12 C. xix, f. 19r

Nicole Eddy