It would be impossible to overstate the cultural significance of Dante’s Divina Commedia (the Divine Comedy), so we won’t even try; suffice it to say that the work has had a profound influence on subsequent authors, painters, sculptors, poets, and filmmakers – even modern graffiti artists and video-game designers. The poem tells the story of Dante’s travels through the three realms of the dead: Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory), and Paradiso (Paradise). He is guided through Hell and Purgatory by the Roman poet Virgil, while Beatrice – Dante’s ideal of womanhood – escorts him into Paradise.

Historiated initial ‘N’(el) of Dante and Virgil in a dark wood, with four half-length figures representing Justice, Power, Peace, and Temperance, with the arms of Alfonso V below, at the beginning of the Divina Comedia, Italy (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450, Yates Thompson MS 36, f. 1r

One of our most recent uploads to the Digitised Manuscripts site is an excellent example of the medieval interpretation of the Comedia. This manuscript, Yates Thompson MS 36, was produced 1444-c. 1450 in Tuscany, probably in the city of Siena, although the identity of the original patron is still unclear. Some scholars have argued that it was made for Alfonso V, the king of Aragon, Naples, and Sicily (r. 1416-1458) who was known to have owned the manuscript in the later years of his life. It was certainly a lavish production, and must have been an expensive undertaking. The manuscript includes more than 110 miniatures created by two of the preeminent artists of the day; Priamo della Quercia painted the illuminations for the Inferno and Purgatorio, while Giovanni di Paolo produced those in the Paradiso.

Below are a number of miniatures from throughout the manuscript; please see here for the fully digitised version.

Detail of a miniature of Dante being rowed by Charon across the River Acheron, from the closing lines of Canto III in the Inferno, Italy (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450, Yates Thompson MS 36, f. 6r

Detail of a miniature of Virgil addressing the carnal sinners Paolo and Francesca, as Dante swoons in horror, in illustration of Canto V in the Inferno, Italy (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450, Yates Thompson MS 36, f. 10r

Detail of a miniature of Dante and Virgil looking into the tomb of Pope Anastasius, and the three tiers of the violent, suicides, and other malefactors, in illustration of Canto XI in the Inferno, Italy (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450, Yates Thompson MS 36, f. 20r

Detail of a miniature of Dante and Virgil witnessing Vanno Fucci, the pillager of a church in Pistoia, being attacked by the monster Cacus, who is half-centaur and half-dragon, and Dante and Virgil speaking to three other souls, tormented by snakes and lizards, in illustration of Canto XXV in the Inferno, Italy (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450, Yates Thompson MS 36, f. 46r

Detail of a miniature of Dante and Virgil witnessing the gigantic figure of Dis, with his three mouths biting on the sinners Cassius, Judas, and Brutus, and Dante and Virgil emerging from the Inferno, in illustration of Canto XXXIV in the Inferno, Italy (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450, Yates Thompson MS 36, f. 62v

Detail of a miniature of Dante speaking to two of the Slothful, while Virgil observes the two Slothful, and the Siren, illustrating Canto XVIII/XIX of Dante's Purgatorio, Italy (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450, Yates Thompson MS 36, f. 98v

Detail of a miniature of Dante and Virgil with others in the heavenly Procession, from the Paradiso, Italy (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450, Yates Thompson MS 36, f. 119r

Detail of a miniature of Beatrice explaining to Dante that the universe is a hierarchy of being, with creatures devoid of reason in the early 'sea of being', and heaven as nine spheres rules by the figure of love, from the Paradiso, Italy (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450, Yates Thompson MS 36, f. 130r

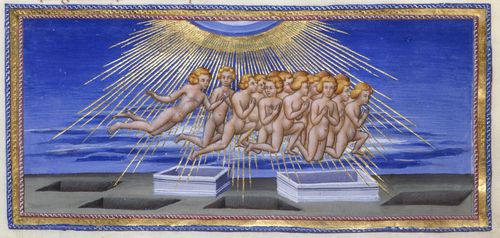

Detail of a miniature of the Resurrection of the dead, from the Paradiso, Italy (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450, Yates Thompson MS 36, f. 154r

Detail of a miniature of Dante and Beatrice before the eagle of Justice, from the Paradiso, Italy (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450, Yates Thompson MS 36, f. 162r

Detail of a miniature of Dante and Beatrice before the Virgin and Child, who are seated within the Celestial Rose, surrounded by various saints, from the Paradiso, Italy (Tuscany, Siena?), 1444-c. 1450, Yates Thompson MS 36, f. 187r

Don't forget to follow us on Twitter: @blmedieval.

- Sarah J Biggs