The British Library is delighted to have loaned three manuscripts to an

major exhibition in Mannheim

at the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen. This exhibition, The Wittelsbachs on the Rhine: The Electoral Palatinate and Europe, will run from 8 September 2013 until 2 March 2014. The exhibition corresponds to an

important period of history, namely the 800th anniversary of the granting of the

County Palatine of the Rhine to the

Wittelsbach family, and celebrates the history, arts and culture of the

Wittelsbach Counts Palatine and Electors.

In 1214, Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen invested the Wittelsbach Duke Ludwig I

with the County Palatine, formerly under the control of the Welf family. This established an unbroken

Wittelsbach line of Counts Palatine which continued through to Carl Theodor, Count Palatine and Duke of

Bavaria (d. 1799). The

Wittelsbachs always referred to themselves as Counts Palatine of the Rhine and

Dukes of Bavaria; emphasis was given to the title of Count Palatine because it included the right to serve as one of the seven electors of the king. This is an exceptional story of the

transformation of a rather obscure family into a dynasty that ruled vast

territories in the Holy Roman Empire for 800

years.

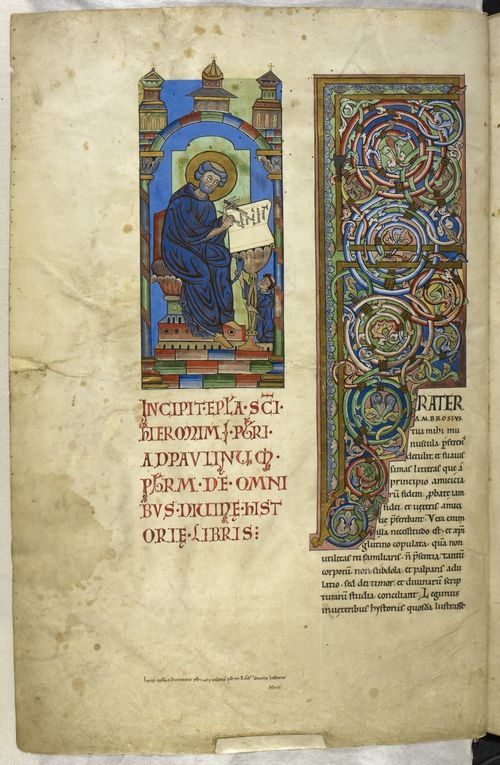

Miniature of Jerome writing at a desk with a small monk below, and the

illuminated initial 'F'(rater) with foliate interlace and bands, at the

beginning of Jerome's letter to Ambrose, Germany (Frankenthal), c. 1148, Harley MS 2803, f. 1v

The

first volume of the Worms Bible (Harley MS 2803; the manuscript is now in two volumes) appears in the first

section of the exhibition, which highlights the importance of the Rhenish Palatine

region. The massive Worms Bible was probably written

or illuminated c. 1148 at the Augustinian abbey of Mary Magdalene in

Frankenthal, 10 kilometers south of Worms, now a

short train ride from Mannheim. If you are unable to make it to the exhibition, you

can view this first volume in its entirely on the Library’s Digitised

Manuscripts website (Harley MS 2803). We hope to digitize the second volume and make it

available on the web in the next several months.

Alongside the history of the Rhenish Palatine region and the Wittelsbach family and its origins, the

concept of the 'Electoral Palatinate' will also take centre stage in the exhibition's first section. The Palatinate was one of the richest and most

important regions in the Holy Roman Empire, a

domain of innovation and creativity.

Co-curator Viola Skiba comments that this remains true today, noting

that ‘it is a common phenomenon that the people call themselves “Kurpfälzer”,

meaning “Palatinates”, without knowing what this signifies'.

Despite the importance of the so-called 'Pfalzgrafschaft'

around 1200, there were only few places of renown in the Palatinate,

but one of these was Frankenthal and its Augustinian monastery, which developed

into a centre of economic and cultural potential with an influence that lasted until

the dissolution of the monastery in 1562 and the consequent dispersal of its

library. In commenting on the relative

paucity of surviving material from the region, Skiba describes the

Worms Bible as 'the highlight and the key exhibit of this first section

dedicated to the region and its cultural and political importance.’

Two other British Library manuscripts feature in the exhibition, both

Hebrew illuminated manuscripts. They are

placed in the second section of the exhibition, which addresses the importance

of the river Rhine and highlights the different cultural

and political aspects of the region. Part of this is a focus on the rich

cultural heritage of the Jewish communities in Rhenish

cities, above all the so-called SchUM cities Speyer, Worms and Mainz (SchUM is

an acronym derived from the initial letters of the Hebrew names of the cities:

Schpira, Warmeisa, Magenza).

Numerous precious manuscripts - now found all over the world - trace

their origins to the region along the Rhine.

Many of these manuscripts are beautifully illuminated and testify to

the high artistic quality of the work done by the scribes and illuminators

employed.

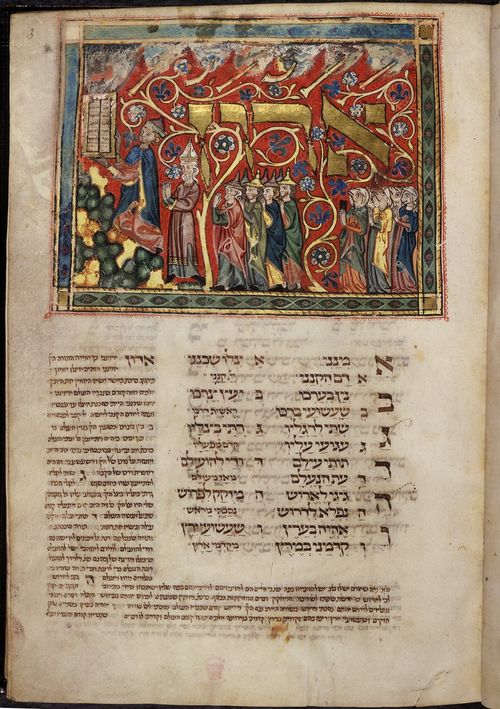

Historiated initial-word panel of the Receiving the Law with Moses streching his

hands for the tablets and Aaron (shown as a Christian bishop) and the Israelites

(divided according to sex) waiting at the foot of the mountain, at the beginning

of a liturgical poem for the first day of Shavuot, Germany, c. 1322, Additional MS 22413, f. 3r

The first manuscript, Additional MS 22413, is a festival

prayer book for Shavuot (Feast of Weeks) and Sukkot (Feast of the Tabernacles). This is one part of the 'Tripartite Mahzor'; the

other two volumes are Budapest (Library and Information Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Science, Kaufmann Collection MS A384), and Oxford (Bodleian Library MS Michael 619). The prayer book was originally a two-volume codex; in the exhibition the first two parts are

reunited and can be viewed side-by-side. Skiba comments that ‘This alone will be one of the absolute highlights of the

exhibition’.

Full-page panel inhabited by hybrids and dragons, and four knights holding

banners with the symbols of the four tribes camped around the Tabernacle (Judah,

Reuben, Ephraim, Dan), and with the initial-word panel Wa-yedabber (and

[the Lord] spoke) in its centre, at the beginning of Numbers, Germany, first quarter of the 14th century, Additional MS 15282, f. 179v

The second British Library Hebrew manuscript to be

featured is Additional MS 15282, the famous 'Duke of Sussex's German

Pentateuch'). This Ashkenazi manuscript, written in Hebrew and Aramaic, was produced in the first quarter of the 14th century by the scribe Hayyim, and contains a number of lavishly decorated word-panels.

Und jetzt in Deutsch!

2013/14 gedenken

die Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen in Mannheim gemeinsam mit der Generaldirektion

Kulturelles Erbe Rheinland-Pfalz, den Staatlichen Schlössern und Gärten

Baden-Württemberg, der Verwaltung der Staatlichen Schlösser und Gärten Hessen,

dem Historischen Museum der Pfalz, Speyer, und dem Kurpfälzischen Museum

Heidelberg einem bedeutenden historischen Jubiläum. Dann jährt sich die

Übertragung der Pfalzgrafschaft bei Rhein an die Familie der Wittelsbacher zum

800. Mal. Mit einer unter dem Titel „Die Wittelsbacher am Rhein. Die Kurpfalz

und Europa“ geplanten, großen Doppel-Ausstellung soll an die Geschichte, Kunst

und Kultur der wittelsbachischen Pfalzgrafen und Kurfürsten gedacht werden.

1214 übertrug der

staufische Kaiser Friedrich II. die vormals welfische Pfalzgrafschaft an Herzog

Ludwig I (1174-1231). Damit wurde eine ununterbrochene wittelsbachische Traditionslinie

begründet, die bis hin zu Carl Theodor (1714-1799) reichte. Über alle Landesteilungen

und dynastischen Zufälle hinweg bewahrten die Wittelsbacher die Verantwortung

für die Einheit von Haus und Herrschaft. Stets nannten sie sich Pfalzgrafen bei

Rhein und Herzöge von Bayern. Der Pfalzgrafentitel stand dabei häufig im

Vordergrund, denn aus diesem konnten die Wittelsbacher das Vorrecht ableiten,

im Kreis der Kurfürsten den König zu wählen und mit ihm gemeinsam die

Reichspolitik zu gestalten.

Die British

Library unterstützt den Ausstellungsteil, der sich mit dem Mittelalter befasst

(um 1200 bis 1504) durch die Leihgabe von drei kostbaren und bedeutenden

Handschriften.

Bei der ersten

Leihgabe handelt es sich um den ersten Band der „Frankenthaler Bibel“, die auch

als „Wormser Bibel“ geführt wird und die im 12. Jahrhundert in Frankenthal

entstanden ist. Die großformatig und wunderbar illuminierte Bibel wird im ersten

Ausstellungskapitel zu sehen sein, das sich der Bedeutung der rheinischen

Pfalzgrafschaft widmet. In dieser Abteilung wird eine außergewöhnliche

Erfolgsgeschichte vorgestellt: der Aufstieg einer bis dahin eher unbedeutenden

Familie zu großer Macht. Die Geschichte einer Dynastie, die schließlich für 800 Jahre große

Gebiete im Heiligen Römischen Reich beherrschen sollten und zu den mächtigsten

Fürsten Europas zählten.

Neben der Familie

und ihrer Herkunft wird dabei auch das Gebiet der „Kurpfalz“ in den Mittelpunkt

treten. Über die Jahrhunderte war die Pfalzgrafschaft eine der reichsten und

bedeutendsten Regionen des Heiligen Römischen Reichs, ein Territorium, das von

Innovationen und Kreativität geprägt war und noch immer geprägt ist. Noch heute

begreifen sich die Bewohner dieses historischen Gebiets, das als solches nicht

länger existiert als „Kurpfälzer“, auch wenn sie gar nicht wissen, was dies

bedeutet. Die Besucher sollen daher dieses besondere historische Territorium,

seine Besonderheiten und seine Herrscher kennenlernen.

Trotz der

Bedeutung der Pfalzgrafschaft gab es in der Zeit um 1200 nur wenige

nennenswerte städtischen oder kulturellen Zentren in diesem Gebiet. Eines war

allerdings Frankenthal mit seinem Augustiner-Chorherrenstift, das sich zu

einem Zentrum von großem ökonomischen und kulturellen Potential entwickelte und das seinen Einfluss für 400 Jahre geltend machte. Im Jahre 1562 wurde das Stift

im Zuge der Reformation aufgelöst. Alle Besitztümer und nicht zuletzt die

Bibliothek wurden auf Befehl Friedrich III nach Heidelberg verbracht und der von Friedrich III der

Universitätsbibliothek hinzugefügt. Um einen der größten Schätze dieser Zeit,

die sog. Wormser Bibel soll die Bedeutung der historischen

Region der Rheinischen Pfalzgrafschaft erklärt werden. Tatsächlich war das

Gebiet im Laufe der Jahrhunderte so umkämpft, dass unglücklicherweise nur wenig

archäologisches Material oder anderes kulturelles Gut die Stürme der Zeit überdauert

hat. Daher stellt die kostbare und wunderbar gearbeitete Bibel das Highlight

und ein Schlüsselexponat für diese erste, der Region und ihrer Bedeutung

gewidmete Sektion dar.

Das zweite

Ausstellungskapitel widmet sich der Bedeutung des Rheins und versucht

verschiedene kulturelle und politische Aspekte rund um den Strom aufzugreifen.

Einer dieser Themenbereiche betrifft die jüdische Kultur im mittleren

Rheingebiet und in der Kurpfalz. Eine

ganze Untersektion ist dem reichen kulturellen Erbe der jüdischen Gemeinden mit

ihren Zentren in den rheinischen Städten, vor allem den sogenannten

SchUM-Städten Speyer, Worms und Mainz gewidmet (SchUM ist ein Akronym, dass sich

aus den Anfangsbuchstaben der hebräischen Namen der drei Städte zusammensetzt:

Spira, Warmeisa, Magenza).

Da das Judentum

essentiell eine auf Schriften basierende Religion ist, bei der die Arbeit mit

Texten und Manuskripten zur Religionsausübung gehörte, kam es zu einer

besonderen Entwicklung der Buchkultur. Zahlreiche kostbare Manuskripte, die nun

über die ganze Welt verstreut sind entstanden entlang des Rheins.

Viele dieser

Handschriften weisen wunderbare Illustrationen auf und belegen den hohen

künstlerischen Standard der Arbeit der Schreiber und Illuminatoren. Mehrere

dieser Manuskripte sind in der Ausstellung zu sehen, darunter zwei Bücher aus

der British Library, ein Pentateuch

und eine Machsor-Handschrift.

Letztere ist Teil eines ursprünglich zweibändigen Werks, das heute in drei

Teilen vorliegt und in verschiedenen Bibliotheken aufbewahrt wird. Für die

Ausstellung in Mannheim wurden zwei dieser drei Teile wieder vereinigt: der erste

Teil des Machsor aus der Bibliothek und Informationszentrum der Ungarischen

Akademie der Wissenschaften und der zweite Teil aus der British Library. Das

allein wird einen der Höheunkte der Ausstellung „Die Wittelsbacher am Rhein.

Die Kurpfalz und Europa“ darstellen.

- Kathleen Doyle and Viola Skiba