Jerry Jenkins, Curator of Emerging Media, Contemporary British Published Collections writes:

In November 2016 I had the pleasure to attend “From Yeats to Heaney: Discovering 140 Years of Literature at the National Library of Ireland” hosted by Embassy of Ireland. After the introduction from the Cultural Attaché and opening remarks from Dr Sandra Collins, Director of the National Library of Ireland, the assembled guests were treated to insightful, often humorous talks on both William Butler Yeats and Seamus Heaney given by Katherine McSharry, NLI Head of Outreach and Professor Geraldine Higgins, NLI Heaney Exhibition Curator respectively. The lectures illustrated the measurable contribution to, and healthy involvement both men had with the National Library of Ireland. It is worth noting that the archives of both Heaney and Yeats rest within its walls.

The British Library has also been fishing in those culturally rich waters which are Dublin. Earlier this year the Library acquired a set of six Sponsors’ Portfolios from the Graphic Studio Dublin.

Between 1962-1979 Graphic Studio Dublin produced a collection of work entitled Sponsors' Portfolios, containing art and literature by writers and artists from Ireland and internationally. In conjunction with their 50th anniversary in 2010 the Graphics Studio re-launched the Sponsors’ Portfolios in 2010.

Each portfolio contains a work commissioned by an acclaimed contemporary Irish writer, and four visual artists. A list of contributors can be found on the Graphic Studio Dublin's website. These showcase the printmaker’s art and the skills which are employed in producing fine press items. Each year a limited edition of 75 imprints are produced. The project will continue to produce folios until 2019 thereby capturing a snap shot of some of the finest work of contemporary Irish writers and artists over the decade. The formula of inviting artists and a writer to work together presents a fresh and vibrant perspective to the interception where visual arts and the written word meet.

Seamus Heaney, 'The Owl'. Translated from the Italian of Giovanni Pascoli. Letterpress. Used with the kind permission of the Graphic Studio Dublin

Poignantly Seamus Heaney contributed to the Sponsors’ Portfolio in 2013, in what turned out to be the year of his death. Entitled Translation, his subject was a translation from the Italian of Giovanni Pascoli poem “The Owl” or “L’assiolo” in the original. The acquisition of this late and rare Heaney work to the British Library is an important addition to the rich collection of Heaney’s writing the Library’s has garnered over the last forty years. My colleague, Dr Richard Price has highlighted some of these in a previous post.

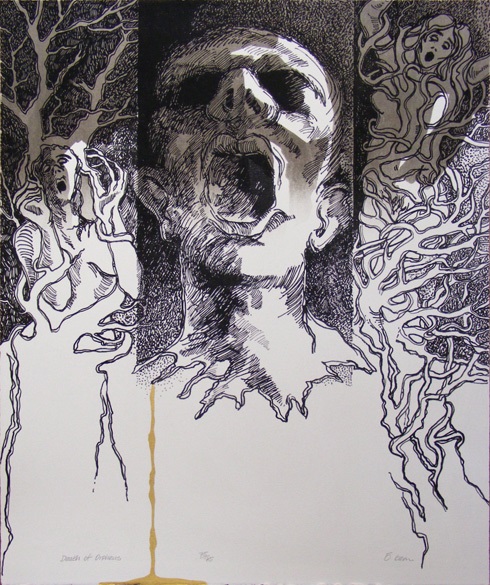

“The Owl” is accompanied by four prints: Pamela Leonard’s “For Sheer Joy ... Took Flight”, Liam Ó Broin’s “Death of Orpheus”, with Jane O’Malley’s “Still Life” and finally Robert Russell’s “Lost in Translation”. These works are beautifully illustrative of how the printmaker’s art can transfer the depth of emotion conveyed in the written word to colour and form of the artist’s reimagining.

Pamela Leonard, 'For sheer joy... took flight'. Etching. Used with the kind permission of the Graphic Studio Dublin

Liam Ó Broin, 'Death of Orpheus'. Lithograph. Used with the kind permission of the Graphic Studio Dublin

If there was any doubt about the truly individual nature these works, when measuring the individual portfolios for their protective phase boxing it was noted that the was a slight discrepancy of millimetres between the size of each of the portfolios. A sure sign of a distinctive and hand crafted nature of these artist’s books.

Jane O'Malley, 'Still Life, La Geria'. Carborundum. Used with the kind permission of the Graphic Studio Dublin

Robert Russell, 'Lost in Translation'. Etching. Used with the kind permission of the Graphic Studio Dublin.

To return to where I started, a thought-provoking question was raised at the “From Yeats to Heaney” event at the Embassy: who will inherit the mantle which seemed so mysteriously to pass from Yeats to Heaney in 1939, (the year of Yeats’s death and of Heaney’s birth)? Within the folios of the Sponsors’ Portfolio might be a good place to start looking for the answer to that question.

In closing, I would urge readers to explore the rest of the series the British Library’s copies of the Sponsors’ Portfolio. 1/10-7/10 are orderable at pressmarks:

Ultramarine, Jean Bardon, Carmel Benson, Roddy Doyle, Kelvin Mann and Donald Teskey RHA., 2010, British Library Shelfmark: HS.74/2280;

Journey, Caroline Donohue, Theo Dorgan, Martin Gale, Stephen Lawlor and Louise Leonard, 2011, British Library Shelfmark: HS.74/2281;

Thoughts, Jennifer Lane, Seán McSweeney, Niall Naessens, Marta Wakula-Mac & Thomas Kinsella, 2012, British Library Shelfmark: HS.75/2282;

Translation, Pamela Leonard, Liam Ó Broin, Jane O'Malley, Robert Russell & Seamus Heaney, 2013, British Library Shelfmark: HS.74/2283;

Thief’s Journal, Yoko Akino, Diana Copperwhite, Ruth O'Donnell, Michael Timmins & John Banville, 2014, British Library Shelfmark: HS.74/2284;

Naming the stars, Colin Davidson, Niamh Flanagan, David Lunney, James McCreary and Jennifer Johnston, 2015, British Library Shelfmark: HS.74/2285;

Pax, Mary Lohan, Tom Phelan, Grainne Cuffe, Sharon Lee and Paula Meehan, 2016, British Library Shelfmark HS.74/2286.

Furthermore, The National Library of Ireland, Trinity College Dublin and Queens University Belfast have also acquired sets of the Sponsors’ Portfolio series.