The British Library's summer exhibition Comics Unmasked: Art and Anarchy in the UK is the UK’s largest ever exhibition of mainstream and underground comics. Many of the works on display, particularly those published from the late 1960s onwards, uncompromisingly address political issues, gender issues, drugs, sex and violence, among other subjects.

A modest section located towards the exit acknowledges the interest in magic and mysticism of comics writers such as Alan Moore, who has famously stated that he regards himself as a magician first and a writer second.

Visitors can view Moore's work alongside the magic book (c. 1581-3) of Elizabethan occultist John Dee, and a notebook (c. 1899) kept by Aleister Crowley while in magical training with the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, whose other members included the poet W. B. Yeats, and the writers of supernatural fiction Algernon Blackwood and Bram Stoker (more about them in the Library's next big exhibition - on Gothic literature).

Born in Leamington Spa, Aleister Crowley (1875-1947) was a poet, writer and mountaineer (also, according to Somerset Maugham, 'the best whist player of his time'1).

He is best known however as the twentieth century's most influential exponent of the practice of 'magick' (Crowley added a 'k' to differentiate his practice from stage magic).

The Oxford English Dictionary defines magic as 'the use of ritual activities or observances which are intended to influence the course of events or to manipulate the natural world, usually involving the use of an occult or secret body of knowledge; sorcery, witchcraft'.

In his lifetime Crowley's activities attracted highly negative reports in the press: a front-page Sunday Express article from 4 March 1923, for example, painted Crowley as 'a drug fiend, an author of vile books, the spreader of obscene practices' and 'one of the most sinister figures of modern times'.

At around the same time the weekly journal John Bull ran a series of anti-Crowley articles with titles such as 'The King of Depravity' and 'The Wickedest Man in the World'. The latter phrase has stuck ever since, cropping up almost without fail whenever Crowley is mentioned in the mainstream media.

Should you be interested, the articles mentioned here can be consulted in microfilm format in the British Library's new Newsroom.

Years after his death, Crowley's dictum 'Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law', and his rejection of conventional religious and societal mores, attracted the attention of the rock and pop generation: in 1967 the Beatles included an image of Crowley on the front cover of their Sgt. Pepper LP sleeve; the Doors posed with a bust of Crowley on the reverse of their 1970 compilation LP 13; Led Zeppelin had Crowley's 'Do what thou wilt' inscribed into the run-out groove of their third album; and unlikely followers Eddie and the Hot Rods used Crowley's image and the 'Do what thou wilt' quote on the sleeve of their 1977 single 'Do Anything You Wanna Do' (i.e. 'Do what thou wilt' rendered in rock'n'roll argot) .

Underground musical artists such as Psychic TV, Coil, and David Tibet's Current 93, have likewise made their interest in Crowley evident in various ways.

When the curators of the Comics Unmasked exhibition requested an audio sample of Crowley speaking, we thought it a good time to take a closer look at the recordings that circulate of his voice.

The first question, naturally, was: are they authentic?

Within the Library's sound archive, suspicions had been aired some years ago that a circa 1990s CD issue of the Crowley recordings (the same set of recordings has been issued over the years by various labels, as we shall see) was unlikely, for various technical reasons, to have been, as stated on the product, a collection of recordings originally made on wax cylinders.

I sent a speculative email to David Tibet, who was the first person to produce an LP-length collection of the Crowley recordings ('The Hastings Archives', GOETIA 666, 1986). David replied immediately, explaining where he had sourced the tapes used for his release ('a Thelemite group run by Kenneth Grant'), and stating unequivocally that the recordings 'are absolutely genuine and absolutely Crowley'.

'The Hastings Archives' is an unusual record in many respects: there is no written information on the outer sleeve beyond the label/catalogue number and the handwritten limited edition number (the Library's copy is numbered 105/418); neither the title nor the name of the artist appears on the sleeve or label at all; one side plays at 45 rpm, the other at 33; and the paper label on mint copies covers the centre hole and has to be punctured so the record can be played. Finally, a contemporary promotional flyer/insert states that 'the plates for LP manufacture have now been destroyed'.

David Tibet put me on to William Breeze of the Crowley Estate who kindly shared with me some liner notes he had previously prepared towards a possible authorized release of the recordings.

These notes quote Crowley's diary entries of 1936 onwards, which make several references to recording sessions, and a letter to the HMV company, in which Crowley, trying to interest HMV in a commercial arrangement, mentions that his recordings were made 'privately in Coventry Street', presumably in a walk-up DIY recording booth. The resulting products would have been 78 rpm lacquer discs (sometimes referred to as 'acetate' discs) not wax cylinders as has been claimed on some issues of the material.

William Breeze says that the original discs are believed lost or possibly in a private collection, but that at least one copy (as in dubbing) of one of the original discs does exist in the Estate's holdings.

I don't know which titles are featured on this disc but it may perhaps have served as the source for the first commercial issue of a Crowley voice recording: a 7" vinyl disc (Marabo UPS 500, 1976), the A-side of which features Crowley reciting two poems, 'La Gitana' and 'Pentagram'. The sound quality here is slightly superior to any subsequent issue of these tracks. The disc is backed with 'Scarlet Woman', a spooky Leonard Cohen-ish rock song performed by a group called Chakra. An insert that comes with the disc (missing from the Library's copy unfortunately) suggests the Crowley recordings were made in the 1940s.

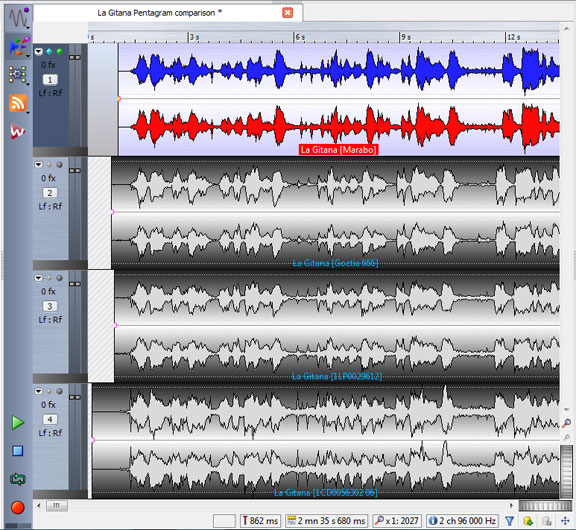

I asked British Library audio engineer Tom Ruane to compare four versions of the same recording, drawn from: (a) the Marabo 7"; (b) 'The Hastings Archives' LP; (c) 'Aleister Crowley' LP (OZ 77, 1986); (d) 'The Great Beast Speaks' CD (DISGUST 1, 1999).

The image above is a screen grab from Wavelab 7 software showing a comparison of the four sound waves. The top one (the Marabo 7") is the 'cleanest' and closest to the source; the next one down ('The Hastings Archives' LP) is a slightly quieter version - and the sound wave is now 180 degrees out of phase, as it is on version (c), which is probably a straight copy of (b).

Though versions (c) and (d) clearly come from the same source (or one that is a generation or two removed), they have had differing levels of compression and equalization applied, to bring out the 'top end' (higher frequencies). All three later versions play very slightly faster than the Marabo 7".

Tom tells me that the noise profiles are in tune with the kind of groove distortion one expects from a 78 rpm disc.

In the world of sound archiving, final judgements on provenance and authenticity sometimes have to be suspended to a degree, especially if one does not have access to the original master copy of the recording under scrutiny. But the circumstantial and technical evidence in this case is fairly persuasive and there seems no reason to doubt that these are indeed recordings of the voice of Crowley.

Copyright regulations do not allow us to post any sound clips here but all the recordings discussed may be consulted at the Library free-of-charge by appointment.

Notes:

1. Crowley served as the model for Somerset Maugham's character Oliver Haddo in his 1908 novel The Magician.

With thanks to William Breeze, David Tibet and Tom Ruane.