05 July 2012

James Berry's 'Windrush Songs'

I was very pleased to be asked to select something from the James Berry archive for Writing Britain as the exhibition has provided the opportunity to display drafts from one of the poet's most significant collections, Windrush Songs, which was published by Bloodaxe Books in 2007. The collection, which consists of three sections 'Hating a Place You Love', 'Let the Sea Be My Road' and 'New Days Arriving' charts the experiences of Berry and others from the Caribbean who felt compelled by circumstances to leave their homelands and seek opportunities abroad. As Berry himself explains in the introduction to the collection the decision to leave was often tempered by mixed emotions as 'here we were, hating the place we loved, because it was on the verge of choking us to death'.

The drafts in the exhibition (one, handwritten notes and, another, an annotated typescript of the poem 'Wanting to Hear Big Ben') illustrate Berry's juxtaposition of Standard English with the rhythm and rhyme of the Jamaican language with which he grew up. At the top of the page of handwritten notes Berry describes Windrush Songs as being a 'Comprehensive and Full Poem Recording Caribbean People's Becoming Part of the British and European Way of Life'. Yet the mixed feelings that I have already mentioned mean the the collection is something of a love letter to the country that Berry left behind. In the 1940s many emigrants' views of England stemmed from their schooling and the colonial relationship that the Caribbean had with Britain. Berry explains how passengers on the SS Orbita 'talked about our own voyage and how we were going to see the England that we'd read about in our school books, where everything was good and shining and moral'. It is easy to understand why they would be keen to see Big Ben, the sound of which had been familiar to new arrivals since they first heard childhood recordings of it -

'and have me rememba, how,

when I was a boy passing a radio

playin in a shop, and a-hear

Big Ben a-strike the time'

As well as this material from the James Berry archive, which the Library acquired in December 2011, the exhibition also includes printed volumes by Berry's friends and contemporaries, Samuel Selvon and Andrew Salkey. Salkey, a writer and journalist was one of the founder members of the Caribbean Artists Movement, in which Berry was also to play a significant role. London has had a long history of welcoming waves of migrants from around the world and I hope that the inclusion of this material goes some way to raise awareness more widely of the important impact of the Caribbean diaspora on British literary life.

These images show James Berry looking at his drafts in the exhibition and further material relating to Windrush Songs in his archive -

29 June 2012

Peasant poets in Writing Britain

While researching the group of items about farming in the Rural Dreams section of Writing Britain, I got really interested in the peasant poet movement. These writers, seen through the sometimes patronising eyes of the 18th and 19th century rich and middle classes, were the authentically rustic voice of the countryside – agricultural workers who published poetry in addition to their ‘day jobs’.

The most famous example is the tragic John Clare, the Northamptonshire son of a farmer who worked variously as a gardener and a barman, struggled with mental health issues for most of his life and lived in an asylum for many years. He experienced great financial hardship whilst trying to support himself and his family through his poetry, and in Writing Britain you can see (in addition to his manuscript draft of his poem ‘Summer Morning’ – Additional MS. 37538 F) his letter to the Royal Literary Fund begging for financial assistance (Loan MS. 96 1/808/7). On the RLF’s file Clare is identified as ‘John Clare, the Northamptonshire Peasant’.

British Library Loan MS 96 1/808/7, Image used with kind permission from the Royal Literary Fund

While Clare’s poetry often focussed on the natural world (he was a skilled botanist), other peasant poets wrote about their working lives. In 1730 Stephen Duck (known as the Thresher poet) published a poem called ‘The Thresher’s Labour’. It describes life as a labourer, and the intense hard work associated with haymaking, but was also notable for its presentation of female labourers as useless chatterboxes who had an easy life and who would work while the master watched but slack off when left to themselves:

‘Ah! were their hands as active as their tongues

How nimbly then would move the rakes and prongs!’

Mary Collier, a washerwoman from Petersfield in Hampshire took issue with Duck’s depiction of the women, and was inspired to write a rebuttal – which also features in Writing Britain. The Woman’s Labour was published in 1739, by which time Duck had received patronage from Queen Caroline and no longer worked as a labourer. Collier wrote a lively and at times humorous depiction of the role of women on farms, the jist of which is that women work just as hard as the men in the fields, with the very great exception that when they go home in the evening, the men can put their feet up while the women cook the evening meal; care for the children; do washing, mending and other chores, and then spend the night getting up to look after screaming babies, before getting up early to make breakfast and repeat the whole process over again:

To get a Living we so willing are,

Our tender Babes into the Field we bear,

And wrap them in our Cloaths to keep them warm,

While round about we gather up the Corn ;

And often unto them our Course do bend,

To keep them safe, that nothing them offend :

Our Children that are able, bear a Share

In gleaning Corn, such is our frugal Care.

When Night comes on, unto our Home we go,

Our Corn we carry, and our Infant too ;

Weary, alas ! but 'tis not worth our while

Once to complain, or rest at ev'ry Stile ;

We must make haste, for when we Home are come,

Alas ! we find our Work but just begun ;

So many Things for our Attendance call,

Had we ten Hands, we could employ them all.

Our Children put to Bed, with greatest Care

We all Things for your coming Home prepare :

You sup, and go to Bed without delay,

And rest yourselves till the ensuing Day ;

While we, alas ! but little Sleep can have,

Because our froward Children cry and rave ;

Yet, without fail, soon as Day-light doth spring,

We in the Field again our Work begin

And there, with all our Strength, our Toil renew,

Till Titan's golden Rays have dry'd the Dew ;

Then home we go unto our Children dear,

Dress, feed, and bring them to the Field with care.

I found Collier’s story really fascinating. Her poem is the earliest description of female labourers written by a female labourer. She worked as a washerwoman for most of her life (retiring from it at the age of 63), and although her poetry had a certain popularity she obviously never made enough money from it to stop working. But The Woman’s Labour was so well-written that evidently authorship was disputed, and the second edition includes a statement from the people of Petersfield confirming that indeed, their neighbour Mary was the author and not some learned male poet.

A final interesting literary link: Collier spent her last few years in Alton in Hampshire, dying in 1762. Alton is very near Chawton where Jane Austen was to move in 1809, and where she died in 1817.

You can read the full text of The Woman's Labour online here, and you can come and see the first edition (and the John Clare manuscripts) in Writing Britain until 25th September.

22 June 2012

"Only a small story ...." Laurie Lee and Cider with Rosie

Last week we heard the first hints about Danny Boyle’s Opening Ceremony for the Olympics. As I wrote in a piece for The Guardian, the ceremony's vision and reception has been infused with literary references. And, particularly, references to Writing Britain. The pastoral idyll that Boyle conjures forth from the ground of E20 is the theme of our exhibition’s opening section- Rural Dreams - that looks at how the restorative possibilities of the British countryside have been celebrated in English literature since the early 16th century. We see this earthly paradise of rural dreams as very much a literary construct- from seventeenth-century poet Katherine Philips’s hymn to T'he Country Life' (as she titled her 1650 poem):

‘How sacred and how innocent

A Country Life appears;

How free from tumult, discontent,

From flattery, or fears!’

…to Edward Thomas’s freeze-framing of time one sunny day in June 1914 (they had sunny days back then) when his train stopped, unexpectedly, in Adlestrop:

‘And for that minute a blackbird sang

Close by, and round him, mistier,

Farther and farther, all the birds

Of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire.'

But what’s most interesting about rural writing is the degree of distance sometimes apparent between the writer and the country life described. Just as Thomas was merely passing through Adlestrop, so many writers describe and remember the countryside while embedded in very different environments.

This was the case for Laurie Lee, whose manuscript for Cider with Rosie with is displayed in the exhibition. Lee’s autobiographical tale describes the moments when the world opened up to his small Cotswolds village of Slad in the years after the First World War, but was written in the early Cold War years.

As Lee recollected, the world that he was writing in was by now far removed –and the stakes so much higher- than the events he was describing:

'I remember towards the end thinking "why am I writing this in a world which is so threatened by the dark clouds and threats of cosmic destruction?" This is only a small story, it can only interest my family and a few neighbours.'

Interestingly, the scrap of paper on which Lee has drafted his novel is a BBC radio script- Lee has turned it over, and used the verso to draft Cider. These are typescripts of radio plays and documentary programmes produced by the BBC and given to Lee by Louis MacNeice, and give a nice sense of a childhood tale of rural life written from, and on, the absolute heart of a metropolitan cultural elite.

15 June 2012

Roughened water

07 June 2012

'A Grim Sort of Beauty'

First published in 1979, Remains of Elmet was a collaboration between photographer Fay Godwin and poet Ted Hughes. The photograph above by Fay Godwin shows the ruins of Staups Mill, which is situated at the top of Jumble Hole Clough, near Hebden Bridge, Yorkshire. In the book it was paired with the Ted Hughes poem 'Mill Ruins'. Hughes grew up in the Calder Valley in West Yorkshire and was fascinated by the way in which the region's wilderness had reclaimed the remnants of the early industrial revolution.

Visitors to the Library's Writing Britain exhibition can view original photographs used in the book together with original letters and manuscripts from the Ted Hughes archive, including letters to Fay Godwin. There are also audio recordings of Hughes talking about the book and reading from it.

Here is an excerpt from a long oral history interview with Fay Godwin conducted by the British Library in 1993, in which she recalls working with Hughes.

06 June 2012

The Water Poet, pageants and the Thames

Diamond Jubilee Thames pageant © Tanya Kirk 3June 2012

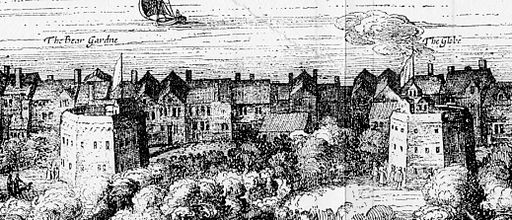

One of the less well-known poets to feature in Writing Britain is John Taylor, the self-styled ‘Water-Poet’. Born in 1578 in Gloucester, he moved to London in his early teens and was apprenticed to a Thames waterman. Watermen were the taxi drivers of the 16th and 17th centuries who, in the days before plentiful bridges across the river, ferried vast numbers of people back and forth between London proper and the theatre district at Bankside.

After a somewhat swashbuckling apprenticeship (at the ages of 17 and 18 he journeyed to Cadiz and the Azores, as part of the group of watermen who were contracted by the navy) he could have just settled down to his profession, but he had other ideas. Taylor decided he would like to be a poet, a sort of Thames poet who would tell it like it is – portraying the river as a dirty but vital force rather than the unrealistically silver “Sweet Thames” portrayed by Spenser and other near-contemporaries.

Taylor’s first book was The Sculler, a collection of poems published in 1612, when he was around 34 years old. It was a cheap pamphlet, featuring a woodcut of Taylor in his boat. The Sculler is currently on display in Writing Britain:

British Library shelfmark C.186.bb.18

(If you're interested, the Latin inscription on the title page is an aggrandised version of the cry of a waterman: "I am the first man. Will you go with me to row? I have the nearest boat.")

In order to finance later works, he hit on a cunning plan. He would perform various crazy stunts, collect subscription money (basically, sponsoring him to carry out the stunt) and use the money to pay the printers. His most famous of these was his attempt to row from London to Quinborough in Kent in a boat made of brown paper, with dried fish tied to sticks as oars. Luckily he also opted for inflated calves’ bladders tied all around the sides of the vessel, or he would probably have drowned fairly quickly.

In 1613 James I’s daughter Elizabeth was to marry. A grand river pageant was devised for the occasion, with some accounts attributing it to Taylor himself. He did write a long description of the pageant and a poem upon the occasion (“Epithalamies”), but made no mention of himself in it – somewhat unusual for such an accomplished self-promoter, if he had indeed had a role in it.

His description of the fireworks on the river focuses heavily on his own explanation of the reasons for describing them, to add to the glory of the King and remind all of his power:

I did write these things, that those who are farre remoted, not only in his Majesties Dominions, but also in forraine territories, may have an understanding of the glorious Pompe, and magnificent Domination of our High and mighty Monarch King James: and further, to demonstrate the skils and knowledges that our warlike Nations hath in Engines, fire-works and other military discipline, that they thereby may be knowne, that howsoever warre seeme to sleepe, yet (upon any ground or lawfull occasion (the command of our dread Soueraigne can rouze her to the terrour or all malignant opposers of his Royall state and dignity.

Taylor’s actual description of the fireworks relies heavily on the phrase ‘many fiery balls flies up into the Ayre’. Other than that, they seemed to have served a very different purpose to fireworks today, being mainly used to represent the re-enacted battle in the pageant, which involved 16 ships, 16 galleys, and 6 frigates. I can’t image people oohing and aaahing over these fireworks; rather, they were meant to be cowering at the power of the Royal Navy.

It all seems a bit less cheerful than the Thames pageant 399 years later (last Sunday). In 1613 they seem to have had better weather but the mock-battle element was a lot more bloodthirsty, and lacked the benefit of an entire boat of Robin Hoods.

Diamond Jubilee Thames pageant © Tanya Kirk 3June 2012

If you’re wondering what happened to John Taylor, he managed to retain his popularity as a poet (albeit a pretty bad one) and his professional career, becoming one of the King’s Watermen; an official spokesman for the Company of Watermen, and publishing a volume of his complete works in the 1630s – a large, grand folio which is an extreme contrast to the cheap quality of his first book. However towards the end of his life his royalist beliefs didn’t serve him well, and he died in poverty in 1653.

You could say that Taylor was about a century before his time. In the 18th and early 19th century ‘peasant poets’ were in vogue, and Stephen Duck (the Thresher Poet), Ann Yearsley (the Bristol Milkwoman) and Mary Collier (the Washerwoman Poetess, also featured in Writing Britain) became popular with the aristocracy as rustically authentic poetic voices. I’m sure Taylor would have seen himself as a cut above the others, but he’d have enjoyed the fame.

02 June 2012

"Why is there so much Dorset in this exhibition?"

I was doing a tour of Writing Britain last week for a group of trainee librarians, and when I asked for questions at the end one of them asked me why Dorset featured a lot in the Rural Dreams and Waterlands sections which I curated. She was from Dorset and had noticed a few references.

Now I'm hoping that I didn't accidentally bias this exhibition into becoming "Writing Dorset", but choosing books for the exhibit list was inevitably going to be a bit of a personal thing. (We knew we couldn't be comprehensive and that's why we created Pin-A-Tale, so people could nominate what we missed out.) As I was born in Dorset and lived there till I was 18, the literature of Dorset was always going to be interesting to me. We couldn't have created this exhibition without including Thomas Hardy, for example, and books like John Cowper Powys' Maiden Castle (Dorchester), Jane Austen's Persuasion (Lyme Regis) and Ian McEwan's On Chesil Beach (er, Chesil Beach) all made their way in too.

But anyway, all of this is a long preamble to me saying that Writing Britain also features Enid Blyton's Five on Kirrin Island Again, which is based on adventures in the Dorset landscape. I was recently contacted by the organiser of the Famous Five Adventure Trail 2012, which kicks off this weekend in the Poole area and runs until September. They will be having a launch event on 7th June, with stalls at every station on the Swanage Railway.

30 May 2012

Sweeney Todd - a heart warming tale?

The Cockney Visions section of Writing Britain features arguably the most legendary barber of all time - Sweeney Todd. Famous for slitting his customer’s throats and covering his tracks by sending the bodies to be made into pies, Todd made his debut in 1846 in a penny blood story called The String of Pearls: a romance. The story begins with the disappearance of a sailor who was bringing a memento to the sweetheart of a man lost at sea. The sailor's faithful dog alerts his friends to his disappearance, whereupon it is discovered that he was last seen entering Sweeney Todd's Barbers. Romance, bravery and carnage follow. This first incarnation, although gruesome, did at least bear the hallmarks of a love story - albeit one peppered with savage murders and the unintentional consumption of human flesh.

An expanded version of the story was published in 1850, this time with the more telling subtitle ‘The Barber of Fleet Street. A domestic romance’. It is this edition that is on display in the exhibition (at a page depicting the ominous barber’s chair and the imminent demise of the unsuspecting man sat in it) and not the 1846 version, in which the illustrations are rather tame [see below].

Later incarnations of Sweeney Todd (of which there are many) tend to gloss over the romantic aspects and more openly embrace the monster lurking behind the barber shop doors.

The idea of a murderer turning their victims into pies would not have been new to many of Sweeney Todd’s original readers. There were several stories and urban legends around at the time that ran along similar veins, which would have provided perfect inspiration for a penny blood story – writers of the genre were never afraid of ‘borrowing’ the odd story line or two. Penny Bloods were serialised fiction that provided cheap, entertaining reading for the working class population of 19th century Britain. The colourful stories full of unsavoury characters and sensational plots were accompanied by gruesome illustrations. They were the violent video games of their day; perceived as corrupting influences that would inevitably pervert the minds of their readers towards depravity and crime. While there is no evidence to suggest that he inspired a generation of amateur butchers, Sweeney Todd’s character has certainly endured - he has become embedded in our culture so deeply that one can almost smell the stench from his abattoir when passing St. Dunstan’s Church in Fleet Street.

Lead Curator of Writing Britain Jamie Andrews can be heard talking about the Writing Britain exhibition during his interview for Radio 4.

Further information about the British Library's world-class literature collections can be found here.

Andrea Lloyd, Curator Printed Literary Sources, 1801-1914

English and Drama blog recent posts

- Invoking the Dunkirk Spirit: Thames to Dunkirk 1940 to 2020

- Penelope Fitzgerald’s Archive: A Human Connection

- ‘What Do I Know About Beckett?’: B.S. Johnson’s Beckett Notebook

- World Poetry Day – listen to new readings from Michael Marks Awards

- The Cambridge Love Letters from Ted Hughes to Liz Hicklin

- Cataloguing James Berry

- Written Britain

- A country life - a poem, the pastoral and the pretender

- Islington: "remote and faintly suspect"?

- Coleridge, Wordsworth and digital mapping

Archives

Tags

- #AnimalTales

- Africa

- Americas

- Animal Tales

- Artists' books

- Banned Books

- Biography

- Black & Asian Britain

- British Library Treasures

- Classics

- Comedy

- Comics-unmasked

- Conferences

- Contemporary Britain

- Crime fiction

- Decolonising

- Diaries

- Digital archives

- Digital scholarship

- Discovering Literature

- Drama

- East Asia

- Events

- Exhibitions

- Fashion

- Fiction

- Film

- Gothic

- Humanities

- Illustration

- Law

- Legal deposit

- Letters

- LGBTQ+

- Literary translation

- Literature

- Live art

- Manuscripts

- Medieval history

- Modern history

- Murder in the Library

- Music

- New collection items

- Poetry

- Printed books

- Psychogeography

- Radio

- Rare books

- Research collaboration

- Romance languages

- Romantics

- Science

- Science fiction

- Shakespeare

- Sound and vision

- Sound recordings

- Television

- Unfinished Business

- Video recordings

- Visual arts

- Women's histories

- World War One

- Writing

- Writing Britain