Selecting 100 magnificent maps from a collection of 4.5 million wasn't easy. Would you like to know how we did it?

I shall tell you anyway.

Although Peter had been developing ideas for an exhibition of display maps arranged contextually for some time, preparations began in earnest in January 2009. We had already established the framework of spaces in which to place the maps (palace, schoolroom etc.), and had a reasonable idea of the sort of messages we wanted the maps to contain. We felt it important to consider any maps which we knew were originally displayed in these spaces (The c.1425 Cottonian map of Italy for example, which was almost certainly owned by Henry VIII and displayed in Whitehall).

We knew of specific maps in the collection which we wanted to include - The Klencke atlas, and the Desceliers world map of 1550, but we felt that other big favourites, like the 'Red-Line Map' of the United States, should not automatically be guaranteed a place. You see, we wanted to show as many objects as possible which had not been displayed before. We decided, therefore, to look at as many maps from the collections as we could, leaving no map unglimpsed. Our criteria for our searches was simple: maps needed a) to have been 'separately issued' - i.e. not published in book form, and b) be visually impressive.

Although there exist records for the British Library's maps on the Integrated Catalogue and various printed catalogues, in none of them are you likely to find information such as 'this is a really beautiful map with wonderful colour.' Library catalogues just don't work like that. So, with a clear grasp of my mission, and armed with a pad of paper and a pencil, I headed solemnly for the basement.

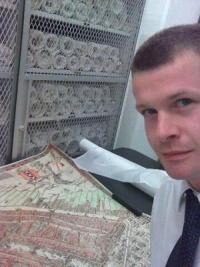

I emerged some 6 months later with a long list of around 800 maps. I'd looked at each of the 1,400 maps stored as rolls (see below), and around 250 portflios containing large maps stored as separate sheets. In addition, I'd looked at each of the 26,000 sheet maps produced before the year 1800. I proceeded to make myself a nice cup of tea.

Above: in the storage area, with the tremendous Cornelis Anthoniszoon map of Amsterdam from 1544 which sadly (and somewhat unbelievably) didn't make the final cut.

Above: These childish scribbles show the selection process in action. We graded maps A - C, A being the best.

To the 800 we also included a significant number of maps from the Manuscript collection, and a small number from the Oriental collections. We had uncovered some absolutely remarkable maps and views, many of which had not been looked at for possibly hundreds of years, but we had enough material for 8 exhibitions.

Reducing the number of maps from 800 to 100 was a long and painful process (not unlike infanticide, Peter observed, as many dear maps were to fall by the wayside). I think we chose wisely, and in accordance with the very strict requirements of the settings. But as an apology to those great maps not included, and to placate those of you whose favourites didn't make it, from next week I'll be featuring in turn the 'Ten Magnificent Maps which didn't quite make the exhibition.'