In this blog post Helen Cowie, Eccles Centre for American Studies Visiting Fellow, writes about her research on the sealskin industry in late-nineteenth century Alaska. Helen will discuss her research as part of the Eccles Centre Summer Scholars Seminar Series

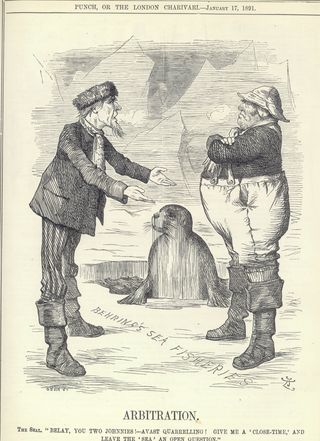

On 17 January 1891, the satirical magazine Punch published a cartoon showing a seal emerging from a hole in the ice. The cartoon depicts the animal propped up on its flippers and looking sagely at two squabbling men. The man on the left, in stripy trousers and cravat, represents the USA, embodied in the familiar character of Brother Jonathan. The rotund man on the right, with bulging stomach and a broad-brimmed souwester, is John Bull, a caricature of Great Britain. The seal addresses them both with soulful gaze, imploring them to ‘avast quarrelling! Give me a “close time” and leave the “sea” an open question’.[1]

Punch’s pithy cartoon was a humorous take on a serious international dispute over the future of the fur-seal fisheries of Alaska. Since the early nineteenth century, the fur seal had been hunted extensively in the Bering Sea for its valuable coat, which was used to manufacture ladies’ cloaks and jackets. By the 1890s, however, seal numbers were fast decreasing, triggering mutual recriminations between the USA and Canada. According to naturalist Henry Elliott, who visited the fur-seal islands of St Paul and St George in the summer of 1890, there were only 959,000 seals present during the breeding season; just a third of the number he had seen two decades earlier in 1874.[2]

Punch’s pithy cartoon was a humorous take on a serious international dispute over the future of the fur-seal fisheries of Alaska. Since the early nineteenth century, the fur seal had been hunted extensively in the Bering Sea for its valuable coat, which was used to manufacture ladies’ cloaks and jackets. By the 1890s, however, seal numbers were fast decreasing, triggering mutual recriminations between the USA and Canada. According to naturalist Henry Elliott, who visited the fur-seal islands of St Paul and St George in the summer of 1890, there were only 959,000 seals present during the breeding season; just a third of the number he had seen two decades earlier in 1874.[2]

The fur-seal controversy centred on the different methods of hunting the animal. The USA hunted the seals on land on the Pribilof Islands, driving young male animals to a designated killing grounds and there bludgeoning them to death. The Canadians hunted the seals at sea, shooting them and spearing them with harpoons in the water. Pelagic sealing (hunting at sea) was regarded as more wasteful, since it killed females, pups and unborn young indiscriminately and mortally wounded many seals whose skins were not subsequently collected. One critic, D.O. Mills, estimated that ‘every skin placed upon the market by [pelagic sealers] represents the destruction of six or eight seals – an utterly unjustifiable inroad into the vitality of the herds’.[3]

‘Killing a “drive” of fur-seals on St Paul’, The Illustrated London News, 24 June 1893

Keen to protect the seals from destruction, the USA limited the number that could be killed on the Islands and began deploying naval vessels in the Bering Sea to seize ships engaged in pelagic sealing. The Canadians, however, disputed the US’s rights to board their ships in what they considered to be international waters and appealed to Britain to defend the rights of their sealers. By 1891, when Punch published its cartoon, the two nations were teetering on the brink of war.

‘Seals at Home’, The Animal World, 1 September 1882

The fur-seal crisis offers an interesting early example of wildlife conservation and its international dimensions. Because the seal was a migratory animal, cross-border cooperation was essential to ensure its survival. The USA could introduce a complete moratorium on the killing of seals on land – as indeed it did in 1911 – but if the Canadians continued to slaughter the animals at sea, their efforts would be futile. Measures taken to protect the fur-seal set a precedent for similar transnational agreements concerning the protection of migratory birds and the preservation of game in colonial Africa.

Another key aspect of the fur-seal debate was the important role played by scientists in the framing of conservation policy. To understand how best to preserve the species, the US Government commissioned several scientific surveys of Pribilof Islands, all staffed by zoological experts. These individuals conducted careful fieldwork on the islands and offered a detailed understanding of seal behaviour and ecology. They used the latest technology to support their studies, backing up their findings with carefully documented evidence. To show that large numbers of seals wounded by pelagic sealers were not subsequently caught, for example, the 1896 commission cited the case of ‘a wet [i.e. nursing] cow’ found at the bay of Polovina on 23 July ‘with bloody shot holes in her shoulder’.[4] To prove that pups required milk until they left the breeding grounds in November, the scientists killed a selection of the animals and examined the contents of their stomachs, which were found, in the vast majority of cases to be either empty (in the case of orphans) or ‘full of milk’ well into October.[5]

‘The Countenance of Callorhinus’, Drawing by Henry W. Elliott, Pribilof Islands, 5 July 1872

Scientists’ observations informed government policies and lent weight to proposed conservation measures, much as they do today. They did not necessarily provide definitive answers, however, for it was often the case that different studies arrived at different conclusions. One US scientist, Henry Elliott, for instance, advocated a moratorium on the land drive, because he believed that repeated driving impaired the fertility of male seals. His compatriot, David Starr Jordan, however, refuted this, arguing that the seal’s reproductive organs were ‘withdrawn into the body cavity when he is in motion, thus being entirely protected from injury’.[6] The Canadian Record of Science, meanwhile, reprinted an article on sealing in the South Pacific in 1893 which appeared to show that the damage there was done on land, and not at sea. We can therefore see science being used to support different national and ideological viewpoints.

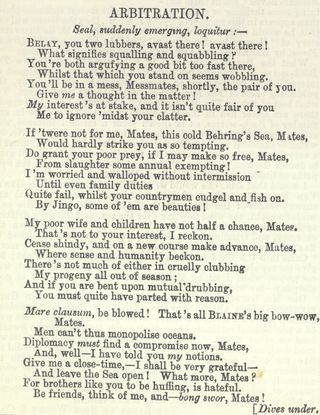

As for the seals themselves, they were rarely consulted in the debate, but Punch at least gave one of them a voice. Next to the arresting image with which this blog post began, the magazine printed a short poem, supposedly written by the seal, in which the plucky animal begs both sides to stop squabbling and ‘Give me a thought in the matter’. In rousing nautical language, the seal complains of being ‘worried and walloped without intermission / Until even family duties quite fail’ - a reference to Elliott’s claim that the seal drive rendered males infertile. He protests loudly that his ‘poor wife and children have not half a chance’ – an allusion to the damage done by pelagic sealing - and he urges both sides to establish a ‘close time’ in which he and his family can recover. Since this is a British publication, it is no surprise that the seal refutes the US’s claim to sovereignty over the entire Bering Sea – ‘Men can’t thus monopolise oceans’. He does, however, advocate ‘compromise’ and friendship between nations, issuing a plea for international peace before he ‘dives under’ the water and departs the scene.[7]

As for the seals themselves, they were rarely consulted in the debate, but Punch at least gave one of them a voice. Next to the arresting image with which this blog post began, the magazine printed a short poem, supposedly written by the seal, in which the plucky animal begs both sides to stop squabbling and ‘Give me a thought in the matter’. In rousing nautical language, the seal complains of being ‘worried and walloped without intermission / Until even family duties quite fail’ - a reference to Elliott’s claim that the seal drive rendered males infertile. He protests loudly that his ‘poor wife and children have not half a chance’ – an allusion to the damage done by pelagic sealing - and he urges both sides to establish a ‘close time’ in which he and his family can recover. Since this is a British publication, it is no surprise that the seal refutes the US’s claim to sovereignty over the entire Bering Sea – ‘Men can’t thus monopolise oceans’. He does, however, advocate ‘compromise’ and friendship between nations, issuing a plea for international peace before he ‘dives under’ the water and departs the scene.[7]

Thankfully the seal’s call was heeded and the USA and Britain reached a compromise agreement in 1893. Seals were granted a closed season from 1 May to 1 October and a sixty-mile closed zone around the Pribilof Islands in which no pelagic sealing was permitted. Eighteen years later, in 1911, a further international agreement banned pelagic sealing completely, triggering the recovery of the fur-seal population. In 1920 conservationist William Hornaday described the preservation of the fur-seal as ‘the most practical and financially responsive wildlife conservation movement thus far consummated in the United States’.[8]

Helen Cowie is lecturer in history at the University of York. Her research focuses on the history of animals and the history of natural history. She is author of Conquering Nature in Spain and its Empire, 1750-1850 (Manchester University Press, 2011) and Exhibiting Animals in Nineteenth-Century Britain: Empathy, Education, Entertainment (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

[1] ‘Arbitration’, Punch, 17 January 1891.

[2] Henry W. Elliott, Report on the Condition of the Fur-Seal Fisheries of the Pribylov Islands in 1890 (Paris:Chamerat et Renouard, 1893), p.91.

[3] D.O. Mills, ‘Our Fur-Seal Fisheries’, The North American Review 151 (September 1890), p.303.

[4] David Starr Jordan, Observations on the Fur Seals of the Pribilof Islands, Preliminary Report (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1896), p.44.

[7] ‘Arbitration’, Punch, 17 January 1891.

[8] The Times, 31 August 1920.