Ahead of next week's TalkScience event on Doping in Sport Julian Walker explores some historical examples of performance enhancement described in his new book "The Roar of the Crowd".

The essence of the debate regarding the use of drugs in sport is: what is an unfair substance to use, and how do we decide? The  dividing line between acceptable and unacceptable is, and for decades has been, constantly moving. For the lay-person the terms ‘anabolic steroids’ and ‘human growth hormones’ sound warning bells, but the equally prohibited ‘diuretics’ sound relatively harmless, and the word ‘stimulants’ requires detailed specification to the point where the word itself is more or less meaningless. How does the cultural history of sport handle this subject?

dividing line between acceptable and unacceptable is, and for decades has been, constantly moving. For the lay-person the terms ‘anabolic steroids’ and ‘human growth hormones’ sound warning bells, but the equally prohibited ‘diuretics’ sound relatively harmless, and the word ‘stimulants’ requires detailed specification to the point where the word itself is more or less meaningless. How does the cultural history of sport handle this subject?

In Book 23 of Homer’s Iliad the funeral games held for Patroclus include a boxing match and a wrestling match. When the boxing match is announced forward comes Epeues, who has certainly done his mental preparation:

"I boast myself To all superior"

His endorphins are running and performance-enhancing even before he has a challenger, his control of the mind-game as assured as Ferguson’s or Mourinho’s. He is answered by the equally confident Euryalus. The fighters each dress for the fight, and:

"Mingling with fists, to furious fight they fell;

Dire was the crash of jaws, and the sweat stream'd

From every limb"

Eurylaus looks for an opening but effectively the fight is over with a single blow from Epeues, and he is taken away, spitting blood.

The wrestling bout is more of a match, Homer pitting brain against brawn, Ulysses against Ajax, neither managing to lift and throw the other. Ulysses then enters the running match, against Oiliades. It’s a close thing, Ulysses is probably tired from the wrestling, and it looks like he is going to lose:

"Oiliades

Led swift the course, and closely at his heels

Ulysses ran. Near as some cinctured maid

Industrious holds the distaff to her breast,

While to and fro with practised finger neat

She tends the flax drawing it to a thread,

So near Ulysses follow'd him, and press'd

His footsteps, ere the dust fill'd them again,

Pouring his breath into his neck behind,

And never slackening pace.[1]"

At this point Ulysses uses the Ancient Greek equivalent of a performance-enhancing drug – he calls on Minerva for help; and sure enough she trips his opponent so that he falls face-down in some cow-poo (ironically his prize for coming second is an ox). Quite blatantly Ulysses has use external assistance to gain victory, and got away with it. Oiliades puts in a complaint:

"Ah--Pallas tripp'd my footsteps; she attends

Ulysses ever with a mother's care."

And what happens?

"Loud laugh'd the Grecians."

It’s a disgrace.

Robert Burton explores, in The Anatomy of Melancholy (1652), the role of exercise in balancing the body. He notes the Roman physician Galen’s contention that ‘to play at ball, be it with the hand or racket, in tennis-courts or otherwise, … exerciseth each part of the body, and doth much good, so that they sweat not too much’[2]. Burton here points out the control on exercise – do it to a certain level of sweating, but stop there; earlier he says that exercise should be done ‘after he hath done his ordinary needs, rubbed his body, washed his hands and face, combed his head and gargarised [gargled]’. These are physical and mental preparations, getting the body empty (I take this to be the meaning of ‘done his ordinary needs’), clean and warmed, and knowing exactly how far to go. While not explicitly involving the ingesting of external substances, they do indicate that exercise does not stand in isolation: the mind and body are made ready for maximum benefit by specific preparation.

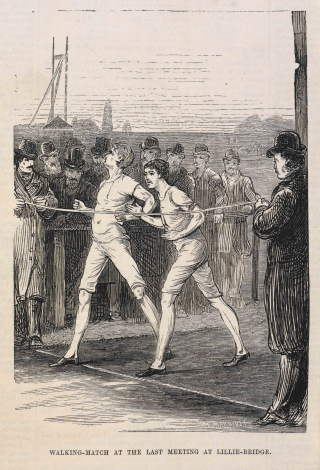

The pre-match preparation of Captain Barclay, the early nineteenth-century endurance athlete, pushed this process further, and was carefully described by Walter Thom in Pedestrianism (1813). Using Barclay as a model, Thom offers a regimen for the preparing athlete, beginning with ‘a regular course of physic, which consists of three dozes [doses]. Glauber salts are generally preferred’. Glauber salt, sodium sulphate decahydrate, is named after Joseph Glauber, who isolated it in 1625, and named it ‘sal mirabilis’ for its supposed medicinal properties; it was used as a purgative (laxative), and is currently deemed acceptable. Thom’s diet list for the aspiring athlete starts with ‘beef-steaks or mutton-chops under-done, with stale bread and old beer’, and goes on to prohibit any ‘preparations of vegetable matter’ other than ‘biscuit and stale bread’. Prohibited foods include veal, lamb and pork, vegetables, as well as fish, butter, cheese, or milk. Profuse sweating is required, induced by running four miles in flannel at top speed, followed by the imbibing of ‘sweating liquor’, made from caraway-seed, coriander-seed, and liquorice, boiled down in cider, after which the athlete is ‘put to bed in his flannels, and being covered with six or eight pairs of blankets, and a feather-bed’ for about half an hour. As regards hydration ‘water is never given alone … avoid liquids as much as possible, and no more liquor of any kind is allowed to be taken than what is merely requisite to quench the thirst’.

The pre-match preparation of Captain Barclay, the early nineteenth-century endurance athlete, pushed this process further, and was carefully described by Walter Thom in Pedestrianism (1813). Using Barclay as a model, Thom offers a regimen for the preparing athlete, beginning with ‘a regular course of physic, which consists of three dozes [doses]. Glauber salts are generally preferred’. Glauber salt, sodium sulphate decahydrate, is named after Joseph Glauber, who isolated it in 1625, and named it ‘sal mirabilis’ for its supposed medicinal properties; it was used as a purgative (laxative), and is currently deemed acceptable. Thom’s diet list for the aspiring athlete starts with ‘beef-steaks or mutton-chops under-done, with stale bread and old beer’, and goes on to prohibit any ‘preparations of vegetable matter’ other than ‘biscuit and stale bread’. Prohibited foods include veal, lamb and pork, vegetables, as well as fish, butter, cheese, or milk. Profuse sweating is required, induced by running four miles in flannel at top speed, followed by the imbibing of ‘sweating liquor’, made from caraway-seed, coriander-seed, and liquorice, boiled down in cider, after which the athlete is ‘put to bed in his flannels, and being covered with six or eight pairs of blankets, and a feather-bed’ for about half an hour. As regards hydration ‘water is never given alone … avoid liquids as much as possible, and no more liquor of any kind is allowed to be taken than what is merely requisite to quench the thirst’.

While none of these steps, however eccentric, look ethically dubious, they do make up a massive control regimen for the enhancement of the athlete’s performance. The commodified successor to Capt Barclay’s ‘red-meat & no veg’ diet was Vin Mariani, the so-called ‘athlete’s wine’, launched in 1863. This popular concoction of red wine and coca leaves, whose stimulant properties were praised by the mostly sedentary great and the good, also happened to aid endurance for athletes and cyclists. Cocaine is now, of course, a banned substance for athletes, but Capt Barclay’s coriander-seed and caraway-seed are both diuretics.

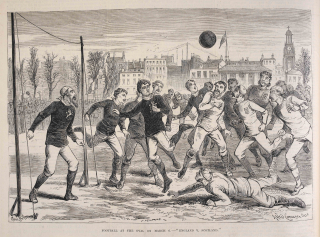

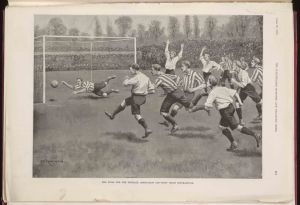

By the end of the 19th century training itself, in some circles, was deemed unsporting. When Blackburn Olympic had the temerity to beat the Old Etonians in the 1883 FA Cup Final the Eton College Chronicle wrote,

‘So great was their desire to wrest the Cup from the holders that they introduced into football a practice which has excited the greatest disapprobation in the South. For three weeks before the final match they went into a strict course of training …’

Blackburn Olympic won 2:1 after extra time. Somehow the Old Etonians had not noticed that the goalposts had moved.

But that perhaps is the question: when we come to look at acceptable or unacceptable substances, can we compare them to laxatives, diuretics, diets and sweating regimes, training or neglecting to train, or even the possible advantage of supreme arrogance, which though it did not work for the 1883 Old Etonians probably helped Epeues? Seeding, records, divisions and trophy cabinets ensure that competing athletes never start on a level playing field. Professional status, sponsorship and training facilities make a real difference to achievement. The ethical paradigms by which we judge acceptable from unacceptable are based on judgements and categorisations that fluctuate all the time. When we compare Phendimetrazine with good old mutton chops are we looking at a difference of kind or a difference of degree?

Julian Walker is an artist, writer, researcher and educator. His latest book "The Roar of the Crowd" is a major new anthology of sports writing that captures the drama, excitement and intrigue of athletic achievement and celebrates the innate urge to compete, to fight, and to test the human body. He is also the author of "The Finishing Touch: Cosmetics Through the Ages" and "How to Cure the Plague and other Curious Remedies".

[1] William Cowper’s translation, 1791

[2] Part 2, Section 2, Member 4.