Last week, Jon Sims introduced some of the archives and collections discussed at this year’s Socio-Legal studies training day on law, gender and sexuality . In this post, Jon looks at British Library resources that address the interaction of law, gender and sexuality during the 20th century

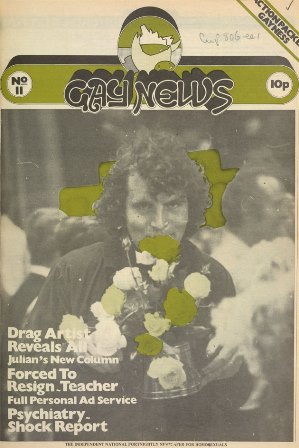

Gay news, issue 11 [1973]

Stepping back in time, Mass Observation Online (available in the British Library reading rooms) provides access to survey material collected by volunteers during and following WWII, on themes including sexual behaviour, family planning, and war time industry. Stepping further back, English translations and academic commentary on classical works by Plato, Aeschylus or Aristophanes provide historical insight on, for example, women’s role in high public office and the military, and female symbolism in the representation of justice. They also support investigation of the cultural impact of classical literature on the judicial and legislative process in the 19th and 20th centuries.

On August 4th 1921, with reference to ancient history and the supposed role of women in the destruction of classical empire and civilization, a proposed amendment to criminalise “gross indecency between females” was introduced by the Criminal Law Amendment Bill (House of Lords, 1921). The Parliamentary debate on the bill reveals varied contexts with which women and same sex sexual relations were framed by the men of both houses (Nancy Astor voted against the clause).

In addition to anecdote from family law practice, reference to the erosion of family structures and social institutions, “feminine morality” and vice, talk of “perversion” is couched in terms of “brain abnormalities” and neuro-science. While the “medico-legal” stance on sexuality enters this legislative discourse in the form of Ernest Wild’s citation (HC Deb 4.8.1921, Vol. 145, Col.1802 – see references at end of this post) of Krafft Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis. Eine klinische-forensische studie, a study published first in 1886 and already reaching an English translation of its tenth edition by the end of the century. The spectre of eugenics is reflected in Lieutenant Colonel Moore-Brabazon’s proposal that when “dealing with perverts” the best policy is to “not advertise them… because these cases are self-exterminating.” (HC Deb 4.8.1921, Vol. 145, col. 1805). Wild’s allusion to Havlock Ellis’ Sexual Inversion brings to mind Ellis’ later work in The Task of Social Hygiene.

The cultural influence of the social hygiene movement in relation to gender and sexuality was discussed by Frank Mort and Lucy Bland (ICA Talks on BL Sounds) in November 1987, less than a month before the introduction of the New Clause 14, later enacted as section 28 of the Local Government Act, prohibiting the promotion of homosexuality “by teaching or publishing material”.

The harder to find parliamentary material for both of these bills can be accessed in the Social Science reading room. A popular cultural perspective can be seen in the Comics Unmasked exhibition, revealing the impact of anti-homosexual legislation and wide spread social prejudice. Friday Night at the Boozer, from AARGH! a benefit comic aimed at organising against the clause 28, captures the pub atmosphere of “ranting, bigoted boozers”. In Committed Comix 'It Don't Come Easy', published in 1977 ten years after the decriminalisation of sexual acts between two consenting men in private, Eric Presland and Julian Howell recount the story of, “a pair of young men on a first date,” who still, “check under the bed to ensure ‘there's no fuzz hidden around’.” The Homosexual Law Reform Society publications (1957 to 1974) also provide valuable insight into the social context in which the law operated with regard to sexuality.

By the time Wolfenden reported in 1957, the Examiner of Plays in the Lord Chamberlain’s Office had, according to Steve Nicholson, “never passed a play about Lesbianism and … very very rarely one in which homosexuality is mentioned.” (Nicholson, 2011). As well as the Wolfenden report itself, readers at the British Library can access correspondence and readers’ reports in the Lord Chamberlain’s Plays Collection (Manuscripts Collections Reader Guide 3: the play collections).

In general, the correspondence files in the Lord Chamberlain’s plays collection reveal the frameworks, such as morality and decency and differentiation between public and private space, within which legislatively empowered censorship, in association with commercial and artistic theatrical interests, negotiated the bureaucratic application of law and its control of the public visibility of diverse sexuality (On the scope of its powers see for example the 1909 Report from joint select committee ..on stage plays (censorship) ). More particularly, attempts to negotiate the Lord Chamberlain’s licence (security against the risk of prosecution) for public performance of one particular play, Jean Genet’s The Balcony (LCP Corr 1965/469), explicitly problematic to the censor for its “major themes of blasphemy and perversion”, including off stage voicing of faked sadomasochistic pain, lasted from 1957 until 1965; or from Wolfenden until just a few years before decriminalisation and the abolition of theatre censorship by the Theatre Act 1968.

A longer look at some of the sources and collections discussed at the training day will feature in the Spring 2015 issue of Legal Information Management. More information about the day’s programme can be found at http://events.sas.ac.uk/events/view/15965, and in the Socio-Legal Newsletter No.73 (Summer 2014)

References

Criminal Law Amendment Bill. HL Bills (1921) [8,a-d etc; 21, a – b & 22].

Harder-to-find House of Lords Bills, such as this one, can be requested from shelf mark BS 96/1. See our guide to Parliamentary Papers for more details.

Parliamentary debates on the Criminal Law Amendment Bill (1921) [HC Deb 4.8.1921, Vol. 145, cols.1799-1807] ; [HL Deb 15.8.1921, Vol. cols. 567 – 577].

Available in the Social Science reading room at BS. Ref. 13 and 14. See our guide to parliamentary proceedings

Standing Committee debate on Clause 28 (SC Deb (A) 8.12.1987, cols.1199 ff)

Available in the Social Science reading room at BS. Ref. 23

Report from the Joint Select Committee of the House of Lords and the House of Commons on the stage plays (censorship); together with the proceedings of the committee, minutes of evidence, and appendices.

British Library shelfmark: Parliamentary papers B.S. Ref 1, 1909 session paper no.303, vol VIII pg 451

Report of the Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution (Homosexual Offences and Prostitution). [the ‘Wolfenden report’]. 1957. Cmnd. 247

British Library shelfmark: B.S.18/158.; Parliamentary papers B.S. Ref 1, 1956-57 session, vol XIV pg 85

Committed Comix: It Don’t Come Easy. 1977.

British Library shelfmark: Cup.821.dd.150.[C]

[Artists Against Rampant Government Homophobia] (1988). AARGH! Northampton

British Library shelfmark: YK.1990.b.10288

Arnot, M; 'Images of Motherhood: Achieving Justice in Nineteenth-century Infanticide Cases' Socio-Legal Studies and the Humanities: conference abstracts

Cohen, D (1987) 'The legal Status and political role of women in Plato’s Laws', Revue internationale des droits de l'antiquité 34 (1987) pp27-40

British Library shelfmark P.P.1898.hab

Ellis, Havelock (1897) Studies in the psychology of sex. Vo. 1. Sexual inversion.

London. British Library shelfmark: Cup.364.b.1.

Ellis, Havelock (1912) The task of social hygiene. London.

British Library shelfmark: 08275.cc.55.

Krafft-Ebing, Richard von (1886) Psychopathia Sexualis. Eine klinische-forensische studie. Stuttgart.

British Library shelfmark: 7641.ff.29.

Krafft-Ebing, Richard von [translated by Francis J. Rebman] (1899) Psychopathia sexualis, with especial reference to antipathic sexual instinct ... The only authorised English translation of the tenth German edition. London.

British Library shelfmark: Cup.363.ff.22.

Homosexual Law Reform Society. [1959]. Homosexuals and the law, etc. London.

British Library shelfmark: 8296.a.13.

Homosexual Law Reform Society. 1963- . Spectrum A.T./ H.L.R.S. Newsletter. London.

British Library shelfmark: Cup.364.ff.1.

Homosexual Law Reform Society. [1965- ]. [Miscellaneous pamphlets and leaflets.] London.

British Library shelfmark: Cup.702.dd.1.

Homosexual Law Reform Society. [1966- ]. Report, 1963-66 [etc.]. London.

British Library shelfmark: P.201/52.

Nicholson, Steve. (2003- ) The censorship of British Drama 1900-1968. Exeter.

British Library shelfmarks: vol 1 (1900- 1932) YC.2003.a.4950; vol 2 (1933- 1952) YC .2005.a.12027; vol. 3 (the fifties) YC.2011.a.16019; vol. 4 (the sixties) forthcoming