Bridget Lockyer, a PhD

student at the University of York, reviews ‘In Conversation with the Women’s

Liberation Movement’ which was held at the British Library in October 2013

‘In Conversation with the Women’s Liberation Movement:

Intergenerational Histories of Second Wave Feminism’ took place on Saturday 12th

October at the British Library. I first heard about this event when I was

approached by Signy Gutnick Allen and Sarah Crook from the History of Feminism Network,

who, along with British Library and the Raphael Samuel History Centre,

were organising the day-long event. My

work on the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) in Bradford and my current

research into women’s paid and unpaid work had prompted them to ask whether I

would like be an ‘interviewer’ on one of the themed panel sessions. Of course I

said yes, this is an event I would have attended anyway, so I was really

pleased to be directly involved. I was also intrigued by the conversation

format and how the intergenerational discussions would transpire.

The event was inspired by Sisterhood

and After: The Women’s Liberation Oral History Project and I really liked

this idea of extending this fantastic project, which I had followed closely,

beyond the confines of its website and archive into an interactive discussion

about the WLM and its legacy. The day would be a series of themed ‘conversations’

with two junior academics/activists interviewing two ‘senior’ academics/activists

who had been involved in the WLM. Each panel would also include a question and

answer session, giving space for the audience to contribute and join in the

conversation.

The event proved to be very popular, selling out twice

(having been moved from a smaller space into the British Library’s conference

auditorium). The unusual format was nerve-wracking, particularly for the junior

interviewers, despite being armed with our pre-prepared questions. There was a

lot to fit in, a range of different topics to cover and I think both the

speakers and the audience were unsure of what to expect.

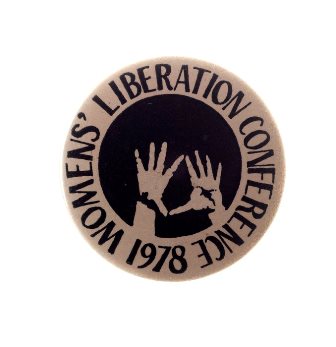

Above: Badge from last National Women's Liberation conference, 1978. Unidentified maker. Available via the Women's Library at LSE.

The first session on ‘Women’s History’ was perhaps the most

interesting for me as a historian. Sally Alexander and Catherine Hall were

interviewed by Lucy Delap and Rachel Cohen. They discussed the close

relationship between the WLM and history, the WLM partly emerging out of a need

to examine women’s own histories and the histories of other women. Yet I was quite

surprised to hear that they were completely confident that they themselves, as

part of the WLM, were actively making history. I

particularly liked the anecdote about Sheila Rowbotham imploring a women’s

group to write dates on their pamphlets and minutes, sparing a thought for

future archivists. They also discussed the WLM’s influence on historical

methodologies and the importance of positioning yourself within your own

research.

In the second session,

entitled ‘Reproductive Choices’, April Gallwey and Freya Johnson Ross

interviewed Denise Riley and Jocelyn Wolfe. The word ‘choice’ was discussed at

length, with particular focus on who had the choice to do what when it came to

reproduction, and the change in the terminology from ‘rights’ to ‘choice’.

Jocelyn discussed how, as a black woman, the concept of reproductive choice was

different, as black women’s bodies were (and are) controlled in different ways.

The panel also discussed motherhood and childlessness, and the class implications

behind the terms ‘yummy mummy’ and ‘pram-face’, again bringing to the fore

questions about language and context.

After lunch, there was the

‘Race’ panel in which Gail Lewis and Amrit Wilson were interviewed by Nydia

Swaby and Terese Johnson. Gail Lewis commented how differently her work was

received and adopted in the United States compared to Britain. Both Gail and

Amrit felt that British feminism has not fully engaged with race and race

politics, particularly within academia. Amrit Wilson discussed feminist

campaigns around immigration, and I was particularly interested in the anti-deportation

campaigns of the 1970s and their links to the WLM. A question from the audience

asked how white women should engage with race within their work and activism.

The panel’s response was simple: educate yourself, read the texts and do not

shy away from it.

The ‘Sexualities’ panel was

the most difficult and tense panel. Both Sue O’Sullivan and Beatrix Campbell,

answering questions asked by Amy Tooth Murphy and Charlie Jeffries, gave

personal accounts of their transition from having only sex relationships with

men to having sexual relationships with women. They considered how sexuality

and gender was perceived during the WLM, discussing bisexuality, political

lesbianism and trans women. During the panel session and the Q and A the

followed, there were quite a lot of angry interjections. There seemed to be

some misunderstanding of what Bea and Sue had said, a confusion between which

views were their own, and which views were the ones prevalent at the time. It

was in this session that the location of the event seemed to jar slightly with

its purpose, and a smaller, more intimate space would perhaps have been more

appropriate.

The fifth session was the ‘Work

and Class’ panel, where Kate Hardy and I interviewed Lynne Segal and Cynthia

Cockburn. Our questions focused on how the WLM tackled issues of women’s work,

what had been learnt and the challenges women face today in the current

political and economic climate. We also discussed the how we could and should

put class politics and socialist politics back into feminist debate and

activism.

The final speaker was Susuana

Antubam, Women’s Officer of the University of London’s Union. She was there

partly to represent younger feminist activism. Susuana spoke about some of the

prevailing attitudes towards women and feminism on our university campuses but

also discussed the multiple campaigns she was involved with, ensuring that the

event ended it on positive, hopeful note.

Not everything about this

event worked, but that is to be expected with an unfamiliar format. Some people

wanted more contributions from the junior feminists and for the dialogue to be

less one-way. I found the conflict that arose frustrating and know that others

too felt disappointed by the lack of unity. Yet the great thing about feminism

in its broadest sense is that it is not afraid to constantly challenge itself

and to keep challenging the assumptions made by those within in it, to ensure,

as Susuana said, that no woman is left behind. In many ways it was good that

the event was not a self-congratulatory ‘pat on the back’ for those in the WLM.

Yet we have got to understand the context in which their mistakes were made in

and appreciate that they were negotiating unchartered territory and forging new

paths. I think this event highlighted some of the differences, intergenerational

or otherwise, between feminists, and the potential for miscommunication between

them. We’ve got to hope that these differences won’t mean feminism presses the

self-destruct button. After all, the common ground is that we were all there,

prepared to listen, eager to take part and willing to continue the

conversation.

Bridget Lockyer is in

the third year of an AHRC funded PhD at the Centre for Women’s Studies,

University of York. Her research interests include women’s experiences of paid

and unpaid work in the UK voluntary sector; voluntary sector culture and change

since the 1970s; feminist activism and its links to voluntary/community work

and oral history methods.

This post was originally published on Bridget’s blog: bridgetlockyer.wordpress.com