Katy Barrett, a final year PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge, writes about the problem of measuring longitude in the eighteenth century and how researching this led her to the British Libary's pamphlet and patent collections.

Blog readers

of a certain age will remember well one of my favourite lines from Nick Park's

animation Wallace and Gromit. As the

villainous robotic dog Preston operates a replica of his Wash-o-matic, Wallace

yells ‘That’s My Machine! I've got patent pending on that!’ This simple phrase

sets Wallace up as the archetypal nutty inventor, who tinkers about with

bizarre machines in his garage and then attempts to sell them to a naive

public. I have kept thinking back to Wallace recently as I have worked on

proposals for a scheme seen as similarly ‘nutty’ in the eighteenth century.

This was the

problem of measuring longitude at sea. By the early 1700s, Europeans had, of

course, been ploughing the oceans for centuries, but it was in this period that

expansion of colonial trade and international naval warfare made it crucial to

be able to get from A to B safely and in a predictable amount of time. To

navigate effectively you need to know your place on the globe in relationship

to two points: latitude and longitude. Latitude is fairly easy to measure by

celestial observations as it is linked to the fixed points of the poles and the

line of the equator. But, longitude has no such stable markers (even the 0

meridian at Greenwich was not agreed until an international conference in

1884), and required the development of accurate instruments and complex

mathematics. The British government therefore passed an Act in 1714 to

encourage proposals of new methods to measure longitude at sea. The Act

established a Board of Commissioners to judge proposals, with staggered reward

money for any successful ones. Proposals could win ten, fifteen or twenty

thousand pounds for finding longitude to within sixty, forty and thirty

geographical miles respectively.1

This

represented a very large amount of money in the eighteenth century, and so

attracted proposals on a broad spectrum from serious inventors, to fortune

hunters, to charlatans. 'The twenty thousand pounds' became a hopeful reference

equivalent to winning one of the popular contemporary lotteries. This meant

that all proposals rapidly became tarred with the same brush in the public

imagination, in press reports, and even used by contributors to discredit their

competitors. In August 1752, the editor of The

Gentleman’s Magazine, John Nichols, found it necessary to publish a notice

‘To the Gentlemen who have sent us Proposals on the Longitude’, advertising

that ‘many schemes have been sent us, which to publish would do no honour to

their authors nor service to the community…some for effecting utter

impossibility…The authors of all such will not, ‘tis hoped, blame us for

suppressing their papers.’2

Likewise,

pamphlets featured criticisms of each other's proposals. 'They're all trying to

con you but me' became a standard argument in published longitude pamphlets.

William Whiston was a particular target of criticism and satire for his 1714

proposal of using rockets sent up from ships moored at specific longitudes.3

A pamphlet by Jeremy Thacker commented of Whiston and his collaborator Humphrey

Ditton, that they had ‘sprung the Twenty Thousand Pounds, and as I hope to get it, I

ought to be civil to them...poor Mr. W-----n

has been so often handled as a Longitudinarian,

and a Latitudinarian…that it

would be as barbarous as ungrateful for me to Insult over him.' This was the satirical

background to the figure solving longitude that William Hogarth included in his

1735 engraving of Bedlam, the contemporary madhouse, in his A Rake's Progress.

Yet,

inventors were also trying to make serious proposals. In 1735 Caleb Smith and

William Ward proposed a new type of quadrant, and in their preface bemoaned how

proposals were so universally ridiculed, saying 'The various Idle Schemes and

Chimerical Projects that have been offered as Discoveries of the Longitude,

have so much prejudiced Men’s Minds against all Propositions of this sort, and

brought so much Disgrace on the Projectors, that every Attempt to solve this

valuable Problem, is now ridiculed as the effect of a weak, or a distempered

Brain.'5 For, the point was, partly, that a trial and monetary

reward from the Board of Longitude provided not only the finances to develop an

invention but also a means of establishing priority and ownership in the ideas

behind it in the days in which the concept of intellectual property was still

in its infancy.

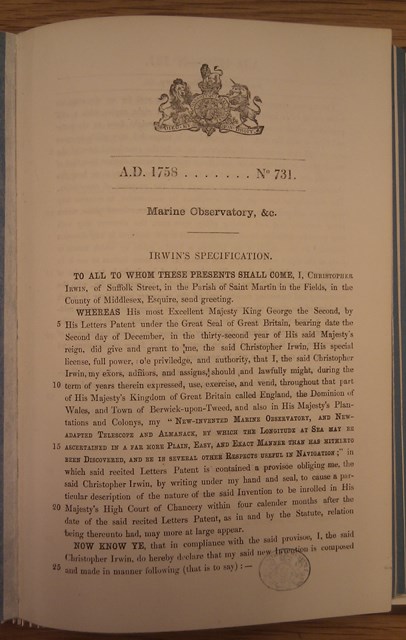

Above: the first page of Christopher Irwin's patent specification of 1758.

The vast

majority of these longitude pamphlets (as well as those that satirise them) are

now in the British Library, and therefore also available on Eighteenth-Century

Collections Online (ECCO). What struck me as I worked on these sources is how

many longitude proposals came to the BL through the Patent Office Library*. The Patent Office was established in 1852, its

creation made possible by the passing of the Patent Law Amendment Act in July

of that year, long after the Board of Longitude was disbanded in 1828. The Act demanded

‘true copies of all specifications to be open to the inspection of the public

at the office of the Commissioners’ and from this requirement developed the

Patent Office Library which opened on 5 March 18556.

The

longitude pamphlets may well have come from the private collections of Bennet Woodcroft

or Richard Prosser which together formed the nucleus of the new library. As Assistant to the Commissioners of

Patents, Woodcroft was responsible for the identification, collation, printing,

abstracting and indexing of early British patent specifications7 and

was first Superintendent of Specifications. Prosser was an engineer and

patent reform campaigner. Both men

recognised the importance of providing a reliable reference collection of

previous specifications and inventions and we know that Prosser’s collection of

around seven hundred volumes included a large number of items published before

1800.

Whatever

their source, despite contemporary satire longitude pamphlets entered the Patent

Office Library as reference works. This

was the result of changes in attitudes to inventing that such pamphlets slowly

helped to foster. For the eighteenth century was the period in which patents

were beginning to resemble their modern descendants: the same decades in which

the authors of longitude pamphlets were attempting to attract backers for their

inventions. These pamphlets attempted to describe their inventions in a convincing

way, and often to include an engraved image to give their idea more

credibility. Thus, longitude pamphlets developed along the lines of patent

specifications, as the rubric of these specs was itself brought to fruition8.

In fact, some of the same people who proposed longitude solutions also sought

patents for their inventions, as different avenues to the same goal of

financial and intellectual security. The 2000 film Longitude, based on the book by Dava Sobel, represents Christopher

Irwin, inventor of the marine chair, as a bumbling fool, but he was

sufficiently clued up to apply for a patent for his chair in 17589

(GB731 of 1758).

The fact,

however, that it is not just patent applications, but a broader group of

longitude pamphlets, that came together in the Patent Office Library, nicely

tells the story of how the library developed precisely from the concerns over

the status of invention that led eighteenth-century commentators to ridicule

such pamphlets. The joke against Wallace over 100 years later, shows that the

ridicule was harder to shake.

*The Patent Office

Library (subsequently the National Reference Library for Science and Invention)

was one of the institutions brought together in 1972 to create the British

Library.

References

(1) The traditional story of the longitude problem and the Board of

Longitude can be found in William Andrewes' (ed.), The Quest for Longitude: The proceedings of the Longitude Symposium,

Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, November 4-6 1993 (Cambridge,

Massachusetts, 1996) [British Library, Document Supply q97/00766]. The papers

of the Board of Longitude are now available through the Cambridge University

Digital Library

(2) The Gentleman’s Magazine and historical

chronicle, vol.22 (August 1752), p.359

[British Library, General Reference Collection 249.c.22]

(3) William Whiston, A new method for discovering the longitude

both at sea and land, humbly proposed to the consideration of the publick

(London, 1714) [British Library, General Reference Collection 533.e.24.(7.)]

(4) Jeremy Thacker, The longitudes

examin'd. Beginning with a short epistle to the longitudinarians, and ending

with the description of a smart, pretty machine of my own, which I am (almost)

sure will do for the longitude, and procure me the twenty thousand pounds

(London, 1714), p.2 [British Library, General Reference Collection 533.f.22.(1.)]

(5) William Ward, The description and

use of a new astronomical instrument, for taking altitudes of the sun and stars

at sea, without an horizon; together with an easy and sure method of observing

the eclipses of Jupiter’s satellites, or any other

phoenomenon of the like kind, on ship-board; In order to determine the

Difference of Meridians at Sea (London, 1735), p.4

[British Library, General Reference Collection 117.d.12.]

(6) The history of the library is told in John Hewish, Rooms near Chancery Lane: the Patent Office under the Commissioners,

1852-1883 (London, c.2000) [British Library, Document Supply m00/37854,

Science, Technology & Business (B) BF 46]

(7) Bennet Woodcroft, Alphabetical

index of patentees of inventions from March 2, 1617 to October 1, 1852 (London,

1969) [British Library, Science, Technology & Business RES (B) BF 482 Law,

Document Supply Wq2/2317]

(8) More on patents can be read in Christine Macleod, Inventing the Industrial Revolution: the English patent system,

1660-1800 (Cambridge, 1988) [British Library, Document Supply 89/02218,

General Reference Collection YH.1989.b.101]

(9) This is based on Dava Sobel, Longitude:

The True Story of a Lone Genius who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of

his Time (London, 1995) [British Library, Document Supply 96/06254, General

Reference Collection YA.1995.a.27311]. Irwin published his invention in A summary of the principles and scope of a

method, humbly proposed, for finding the longitude at sea (London, 1760)

[British Library, General Reference Collection C.194.b.349].

A note on the author: Katy Barrett is a final year PhD Student on the AHRC-funded

project 'The Board of Longitude 1714-1828: Science, Innovation and Empire in

the Georgian World' jointly hosted by the Department of the History and

Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge and Royal Museums

Greenwich.

She works on the cultural history of the longitude problem, about which you can

hear more in a 'PhDCast' done with CRASSH (Centre for Research in the Arts,

Humanities and Social Sciences) at Cambridge.

Katy blogs and tweets as @SpoonsonTrays.