Ian

Cooke, co-curator of Propaganda: Power and Persuasion showcases some of

the photographs and messages created by members of the public during

the 'Write, Camera, Action!' days at the end of July. - See more at:

http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/socialscience/2013/08/write-camera-action.html#sthash.KM288701.dpuf

Ian Cooke, co-curator of 'Propaganda: Power and Persuasion' writes about how radio programmes such as 'The Kitchen Front' were used to communicate with the public about rationing and food-use during wartime.

In our exhibition, Propaganda:

Power and Persuasion, you can hear an excerpt from the BBC radio programme The Kitchen Front. Broadcast on 20

December 1941, it features the characters Gert and Daisy, giving a recipe for

mutton cooked as turkey (“murkey”).

The Kitchen Front

was broadcast daily, following the 8am news bulletin, and was one of the BBC’s

most-popular shows during the Second World War, with regular audiences of 5- 7

million. The programme was conceived as a means by which the Ministry of Food

could communicate with the British public, explaining about rationing schemes,

encouraging the use of foods which were more generally-available, and

discouraging food waste. Additionally, the programme intended to boost morale,

using humour and characters who were recognisable or familiar to the listening

public.

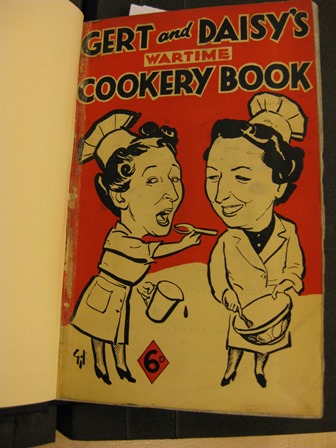

Gert

and Daisy were the creations of performers Elsie Waters and her sister

Doris Ethel Waters. The characters were already popular before the War, having

appeared at two Royal Variety performances in the 1920s and 1930s and releasing

recordings of their sketches and songs. For two weeks in April 1940, Gert and

Daisy performed Feed the Brute, a 5

minute programme broadcast at the end of the 6pm evening news, to give recipes

and advice on food. The use of humour, and popular characters, was a huge success.

Above: Gert and Daisy's Wartime Cookery Book

Public response to the April 1940 broadcasts were analysed

by Mass

Observation, who interviewed 300 listeners in London and Lancashire. The

survey found that positive comments outweighed negative by 8 to 1, and that the

information given on food was regarded as useful. Referring to the use of

comedy in the broadcasts, Mass Observation concluded, ‘This experimental series was an undoubted success, and revealed a

valuable new method of giving out serious educational instruction to millions

of housewives’ – comparing this approach to more “high-brow” forms of

delivery, the authors state, ‘Gert and

Daisy knock spots off Professor Harlow’s Empire Crusade’. However, it

wasn’t just the comedy and popularity of the characters, but also their

apparent familiarity, that was seen as effective. The language used in their

dialogue, and their working class London accents, made them identifiable to

their target audience. The two criticisms of the programmes related to the

perceived extravagance and complexity of the recipes (a complaint that would

persist through The Kitchen Front

broadcasts), and the timing of the programme. Many women commented that they

were too busy to listen at this time in the evening.

Within two months, The

Kitchen Front began broadcasting at the earlier time of 8.15am, following

the news broadcast. Following on from the success of Feed the Brute, popular broadcasters and use of humour were the

show’s staple ingredients. Alongside Gert and Daisy, series regulars included S P B Mais, Freddie Grisewood

(best known for his later role as chair of the series Any Questions?), and Mabel

Constanduros (performing as the Buggins family).

The popularity of the programme was marked by letters sent

to the presenters, addressed both to the BBC and Ministry of Food, suggesting

recipes and asking for more information. Recipe books from the series were

published regularly, and included listener suggestions (described by S P B Mais

as, ‘invitations to adventures in the

unknown’). As well as broadcasts on the radio, demonstrations were held at

schools, factories and other public places.

Throughout the war, the BBC remained active in evaluating

the impact of all its broadcasts, and, as one of its most listened-to

programmes, The Kitchen Front

featured in many of its reports. As well as commissioning research from Mass

Observation, public opinion was monitored through the BBC’s Listener Research

Department. Listener Research was set up in 1936, using social research methods

to develop reliable indicators of listener habits and preferences. As well as

quantitative estimates of audience figures, qualitative methods were used to

understand listener values and behaviours. Methods had much in common with Mass

Observation, which was set up in 1937, and the Ministry of

Information’s own Home Intelligence Division. At the start of the War, the

Listener Research Department set about creating a cohort of 2,000 listeners who

would be asked to complete monthly questionnaires. The questionnaires would ask

about specific programmes and viewing habits, but also about attitudes relating

to the war, and more general matters of personal taste. This information

supplemented the daily interviews conducted with a changing sample of 800

members of the population, used to determine audience figures.

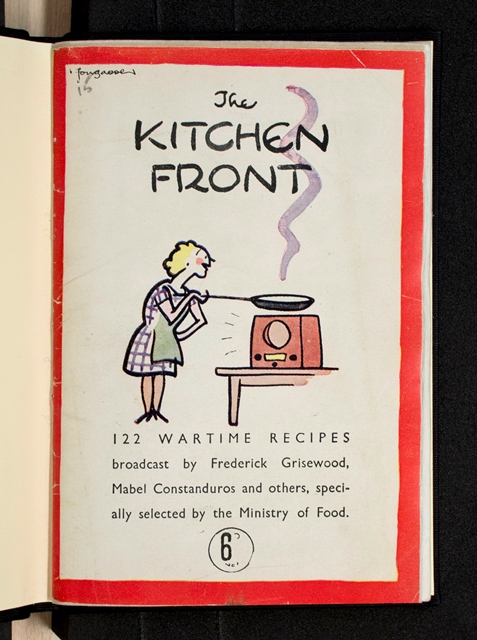

Above: The Kitchen Front - 122 Wartime Recipes

As the war continued research showed that, while audience

numbers held up, the popularity of The

Kitchen Front began to wane. BBC Listener Research in 1942 showed that 31%

of those expressing an opinion thought that the quality of the programme had

deteriorated. By 1943, the series was described as ‘going off’’. Reasons for the decline were uncertain, with the 1943 report

suggesting that, ‘It may well be that the

charge of declining quality is no more than a reflection of the housewife’s

increasing weariness of the whole business of catering under wartime

conditions’. A Home Intelligence Division report titled ‘Housewives’

attitudes towards Official Campaigns and Instructions’, dated 14 May 1943,

suggested a similar problem for home propaganda more generally. The report

argued, ‘housewives are now impervious to

“the flood of official propaganda” and that they select from it only the

information that seems essential to them.’ Cinema and radio faired better

than other formats with posters and leaflets being seen by some at this time as,

‘a waste of paper’.

Radio broadcasting was seen as highly important in influencing

opinion and behaviour in Britain during the Second World War, and became viewed

as a more durable medium than print-based sources. The BBC was therefore of

high strategic importance (its only competitors were enemy stations such as

Radio Hamburg, broadcasting to Britain), and research on public opinion seen as

vital in maintaining effectiveness and understanding what worked in gaining

public support. The research methods developed and used by Mass Observation and

the BBC’s own Listener Research Department became an essential tool in

Britain’s war effort.

References and sources used

BBC Listener Research Department. 1942 (February). Trend in the quality of ten long series.

LR/770.

BBC Listener Research Department. 1943 (July). Trend in the quality of long series.

LR/1973. (Accessed via British Online Archives, available in the

British Library’s Reading Rooms.)

1941. Food Facts for

the Kitchen Front: A book of wartime recipes and hints. British Library shelfmark: 7946.aa.15

P.J. Bruce (ed.). 1942. The

Kitchen Front: 122 recommended recipes selected from broadcasts by Mabel

Constanduros, Freddie Grisewood, etc. British Library shelfmark: 7946.df.24.

Ambrose Heath. 1941. Kitchen

Front recipes & hints: Extracts from the first seven month’s early morning

broadcasts. British Library shelfmark: 7945.p.12

Ambrose Heath. 1941. More

Kitchen Front recipes: Further extracts from the early morning broadcasts with

other recipes and hints. British Library shelfmark: 7946.a.17

S.P.B. Mais. 1941. Calling

again: My Kitchen Front talks with some results on the listener. British Library shelfmark: 7946.a.8

Mass Observation. 1940 (April). Gert and Daisy’s BBC talks. File Report 77.

Mass Observation. 1941. Home

Propaganda: A Report Prepared by Mass-Observation for the Advertising Service

Guild.

Accessed via Mass Observation Online, available in the

British Library’s Reading Rooms

Ministry of Information. 1943. Housewives’ attitudes towards official campaigns and instructions.

Home Intelligence special report number 44, 14 May. Available at The National Archives, reference

INF

1/293

Siân Nicholas. 2006. The good servant: the origins and

development of BBC Listener Research 1936-1950, Accessed via British Online

Archives.

Last updated: 27 February 2008.

(Available in the British Library’s Reading Rooms)

Dorothy Santer (ed.). 1944. The Kitchen Front: Recipes broadcast during 1942-43 by Frederick

Grisewood, Mabel Constanduros and others, specially selected by the Ministry of

Food. British Library shelfmark: 7948.a.16

Elsie & Doris Waters. 1941. Gert & Daisy’s Wartime Cookery Book. British Library shelfmark: 7945.p.9