This guest post from

Stephanie Minchin highlights some of the discussions on ‘Addictive Personality’ as presented at the British Library’s ‘Myths and Realities’ public debate on 18th

March, 2013; with Prof. Phil Withington,

Prof. David Nutt and Prof. Gerada Reith, reflecting upon what drives addiction.

As

part of the ‘Myths and Realities’ series of public debates the British Library

was host to Professor Gerda Reith, University of Glasgow, Professor David Nutt, Imperial College London and Professor Phil Withington, University of Sheffield who

discussed and challenged the myths and assumptions attached to the concept of

addiction. The event was chaired by Claire Fox from the Institute of Ideas who

questioned the notion of an addictive personality with the term that society

may be a nation of ‘addiction addicts’.

Prof.

Phil Withington introduced the debate with ‘Addiction

– an early modern perspective’. The language of addiction from the 16th

and 17th century was described in the depiction of a cloth worker in

1628 as being “overtaken with drink”.

The point was raised that the way we consume and think about intoxicants is

reflected in the understanding of ourselves and where we come from. Therefore,

it seems to some extent that today’s perception of addiction reflects the same

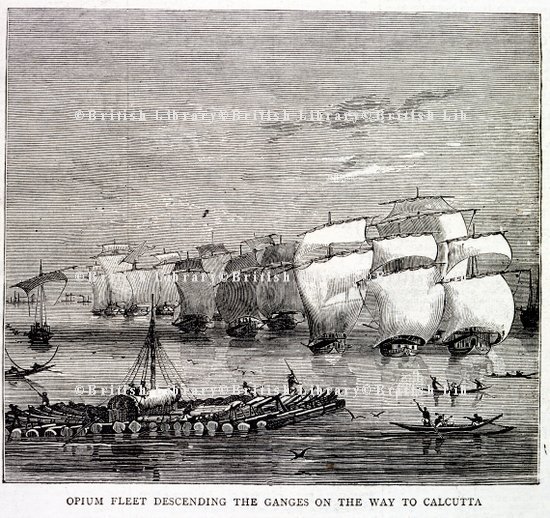

as the early modern roots. Prof. Withington accounted for a historical

perspective of intoxication and capitalism, such that substance use grew into a

big business as an important feature of international trade in the industrial

revolution; organized import and export allowed for the transfer of intoxicants

(tea, coffee, chocolate, opium) as durable and profitable substances. The

language from the renaissance period to today has also increased in the number

of words used to describe the meaning addiction. Samuel Johnson’s (1740)

reflection “he addicted himself to vice”

still holds meaning today.

'Opium fleet descending the Ganges on the way to Calcutta'. Image taken from The Graphic. Originally published/produced in London, June 24, 1882. © The British Library Board

Following

from Professor Withington’s portrayal of the language of addiction, Professor

Nutt began with the translation of the Latin verb ‘addictio’ meaning ‘to

enslave’. Professor Nutt firmly contended that he has never met an addict

who wanted to be an addict, and used Amy Winehouse as an example of a great

loss in a person who struggled to escape the pattern of addiction. From a

biological and neurological perspective Prof. Nutt highlighted pleasure seeking

behaviours as a natural evolutionary mechanism for the survival of the species.

However, in an addiction, it is the compulsion, pressure and drive to change

the brain with a substance that creates a loss of control. The brain circuits

of addiction were detailed as self-control, pleasure, salience/attention, learning

and memory and individual differences that all happen differentially in people.

With the example of tobacco and alcohol the audience was encouraged to

reminisce on their very first taste of a cigarette/alcohol, unanimously

agreeing that it evoked an instant dislike. So what is it that leaves us

wanting more? The biology is all about how fast and how much of the substance gets

to the brain. The faster the substance gets into the brain, the higher the

addiction. In withdrawal, the quicker the substance is secreted from the liver,

the higher the addiction. Prof. Nutt concluded his presentation from a

political perspective to challenge the associated stigma and blame of societal

problems with substance use; in order for Government to provide interventions

and rational treatments for addiction, we need to de-stigmatise those suffering

and understand that addiction is “not a

lifestyle choice”.

Professor

Gerada Reith encouraged the audience to think beyond the individual to consider

the sociological complexities and ambiguities behind addiction. Prof. Reith’s

presentation titled ‘If addiction did not

exist, it would be necessary to create it’ portrayed the reality of

addiction as being a combination of environmental, political, cultural and

historical contexts. In a laboratory experiment titled ‘Rat Park’ it was found

that the group of rats in a small cage became addicted to morphine, whereas the

rats in the ‘social housing’ cages (with light, space, toys and other rats for

company) did not. This experimental finding highlights the differential

behaviour patterns associated with contrasting living circumstances. Therefore,

Prof. Reith highlighted that geographical areas with certain populations and

social groups may experience poorer housing and health, poverty, high rates of

unemployment, short life expectancy and a low level of education, which in turn

can lead to a vulnerability to addiction.

The

concept of environmental influences was further supported by the notion that

the social climates within cultural contexts attach meanings and values to

social activity. In the case of substance use, Howard Becker’s (1953) book

titled ‘Becoming a marihuana user' detailed how jazz musicians of the 1950s

attached meaningful social activity to smoking marihuana, whilst it was

condemned by other social groups, conveying the juxtaposition of cultural core beliefs ‘cool’ vs. ‘deviant’. Further social tensions

were described in the historical use of opium which created racial tensions

between societal classes; consumption was very different in function for the

degeneracy vs. middle-class. In agreement with Prof. Nutt’s political stance,

Prof. Reith contended that the association of crime and unemployment with drugs

has blamed individuals for universal social problems. Today, drugs are the “ideological fig leaf to place over unsightly

urban ills” (Jimmie Reeves and Richard Campbell 1994). The term addiction now

has a cultural specificity and popularity in its label. Addiction as a term and

meaning is normalised; addiction is a discourse in its widest sense.

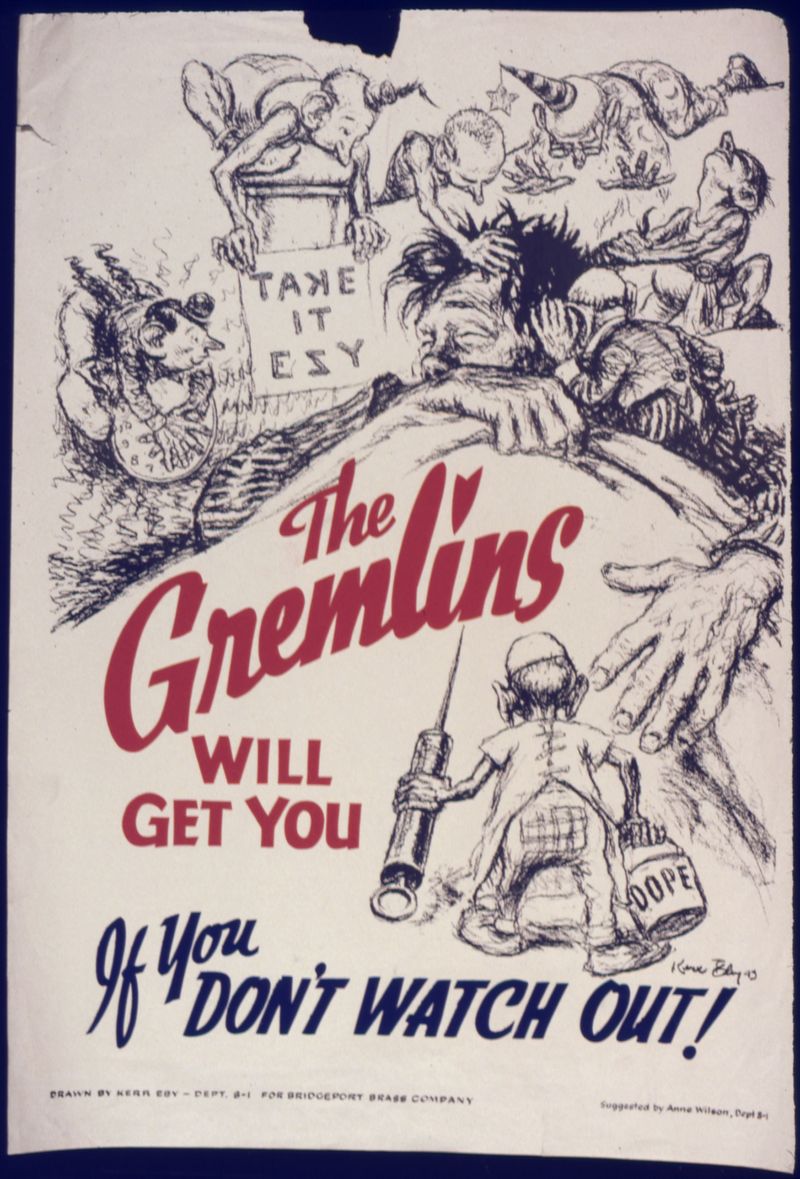

'The Gremlins will get you if you don't watch out!' US Office for Emergency Management. War Production Board. (01/1942 - 11/03/1945). This file was provided to Wikimedia Commons by the US National Archives and Records Administration.

'The Gremlins will get you if you don't watch out!' US Office for Emergency Management. War Production Board. (01/1942 - 11/03/1945). This file was provided to Wikimedia Commons by the US National Archives and Records Administration.

The

discussion was then opened to the audience for questions, comments and thoughts

on the topic. The first question asked do we lack individual responsibility for

our own pleasure-seeking behaviours, and to what extent does the economic

determinism of social deprivation account for substance abuse? The answer was a

medley of biological vulnerability and lack of social opportunity with Prof.

Nutt clarifying “Never does one drug

addict everyone”. Questions continued to scale the continuum of biological

vs. sociological factors, inquiring about addictions influenced by life events;

peer pressure; endorphin pleasure factors; pharmaceutical companies; prohibition

issues. At the moment society has an absolutist view against addiction. Can we

really drink and use substances without losing control? Definitions and cultural

power lie in the hands of medical professionals who influence how we understand

addiction and the changing meanings of substance abuse. Regardless of what

‘type’ of addict one may be defined, be it compulsive or impulsive, the younger

you are when you start the more likely you are to be an addict. The youth is

the real target; the future needs to address addiction at community level.

In

conclusion, the audience were left with provocative final thoughts: Prof. Reith

highlighted the individual brain as a starting point within a cultural

environment predisposing addiction. Alternatively Prof. Nutt posed the question

‘Why in our brain do we have the

propensity to become addicted to substances?’ His answer? ‘It is all about LOVE. Substances are

hijacking the pathways of love.’ For the reality of addiction we are now

contemplating a new myth: are substances a surrogate for love?

Combining

the understanding of historical, biological and socio-cultural perspectives

will help find further answers in what is an undeniable reality of today’s

modern society: addiction. The new myth: drugs or love?

Stephanie Minchin is a

practitioner in NHS mental health services for ‘City and Hackney Centre for

Mental Health in' the East London Foundation Trust’ and is a Masters student in

Clinical Research at City University, London.