Yesterday, 14th November 2012, was the 90th anniversary of the BBC and the beginning of what was to become 'public service broadcasting' in the UK. It began with a 6 pm news bulletin read by Arthur Burrows and has continued daily, if not continuously, since that time, interrupted only by the occasional power cut.

It’s hard to imagine today what a groundbreaking moment it was, changing forever the way people acquired knowledge and information, the way their tastes and interests developed and in the way they experienced entertainment of all kinds.

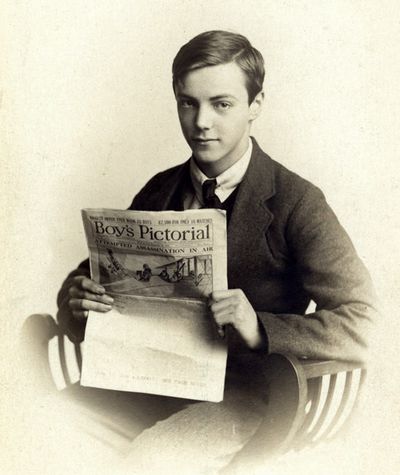

Alfred Taylor in 1922, the year he began writing his Wireless Log and Minutes Book

On the BBC’s Radio Reunited programme celebrating the moment, Damon Albarn put two of the most commonly asked questions to staff of the Science Museum where part of the original 2LO transmitter is now on display. His first was “Who was listening?", to which he was correctly told that they were “amateur radio enthusiasts”.

But I suspect that what Albarn really wanted to know was – What kind of people were listening in the first days of broadcasting? Were they largely hobbyists, scientists and wealthy people? Or did ordinary workers, the retired and young people – the people who make up the bulk of today’s audiences – also get a chance to witness these historic events unfolding? We know there were listeners in London and the South East – but what about the small villages and towns of the north? What would they have heard, if anything, during those first days of transmission? And how easy was it to set up the equipment and tune in?

A unique manuscript recently donated to the British Library by sisters Annie Bright and Susan Briars gives a fascinating first-hand insight into these and other questions – a ‘Wireless Log’ kept by their 16 year old uncle Alfred Taylor (1906-1985) over the 12 months from October 1922 (three weeks prior to the first BBC broadcast) through to 1923.

Taylor, the son of a Newark jeweller by this time resident in Lincoln, had recently won £200, then an enormous sum, in a competition in the short-lived newspaper Boy’s Pictorial (sic) – more than enough to cover the cost of the equipment, aerial installation and the regular ‘radio suppers’ he was to host for interested friends and neighbours over the following year.

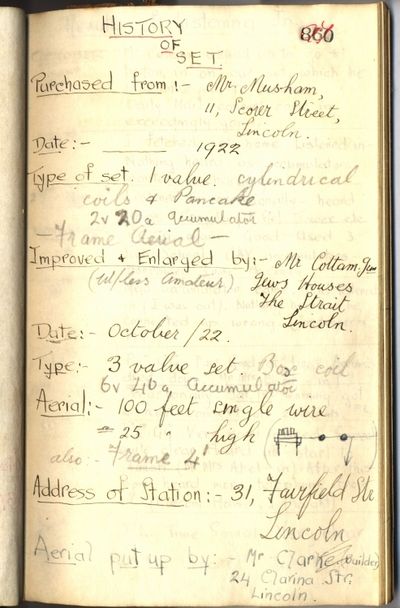

The more powerful multi-valve sets of the kind Alfred bought then cost about £5 – equivalent to more than £200 today. One valuable aspect of his log is the detailed record he made of his equipment, including indoor and outdoor aerials, and how it was set up. He also noted the problems he experienced and the measures he took to resolve them.

The Wireless Log, page 2 [click on image to view full size]

There was no mechanism for measuring audiences at the time. However the Postmaster-General had issued nearly 36,000 licences for BBC-approved wireless sets by the end of 1922 and thousands more had already built their own sets from widely available components in preceding years, suggesting that over 50,000 set owners were probably attempting to tune-into the first BBC broadcasts. But Taylor’s log shows that for every one of these set-owning “enthusiasts” a great many more people, owning neither licences nor equipment, made up the bulk of the first radio audiences.

They were the friends, family and neighbours who dropped in to share the revelatory experience of listening for a few minutes here and there, whenever they were allowed.

The Log also provides a more detailed answer to Albarn’s second question: "How far away was the furthest listener?” This depended on your equipment and on atmospheric conditions but the BBC’s 1,500 watt 2LO transmitter at Marconi House, London could certainly be picked up in Lincoln (East Midlands) with a three-valve receiver and outdoor aerial of the kind Alfred had. Sets with up to seven valves could have received the station considerably further afield, one 2LO listener even being reported in the Shetland Islands. Taylor’s records also show that it was possible to receive Marconi’s still operating experimental station at Writtle (21st Nov), the 4,000 watt station on the Eiffel Tower in Paris (call sign FL – 20th Nov etc), aircraft navigation signals from the Croydon aerodrome and, apparently most clearly of all – the 8,000 watt long-wave commercial radio station P.C.G.G. transmitting from The Hague in Holland. The latter’s clear reception, despite its distance, was due to its much greater power and uninterrupted view across the North Sea to the UK’s eastern seaboard.

We can also see how the quality of the teenager’s reception fluctuated owing to the vagaries of the weather and atmospheric conditions, and the limits of the accumulators (rechargeable batteries) powering the valves. At this time such equipment could not simply be plugged into the mains supply of a house because supply frequencies had yet to be standardized. So in these early months Taylor would probably have had to take the discharged accumulators to his local cycle repair or hardware shop for re-charging – a considerable inconvenience to regular valve set listeners. People using the cheaper and much weaker crystal sets, which used no power, would not have had this problem but had to content themselves with the much more limited reception range and low volume headphone output.

The first page of the log shows that although he was hearing sponsored concerts before the BBC’s first (official) programme went out on the 14th November, the historic date itself passed without comment by Alfred, perhaps because atmospheric conditions were poor, because he listened only “occasionally” or because he’d been unable to recharge the exhausted accumulators.

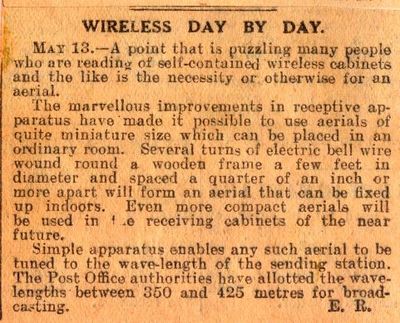

Wireless Day By Day - The Daily Mail, 13th May 1922

He also kept a scrapbook into which he pasted a regular Daily Mail column for wireless enthusiasts titled Wireless Day By Day. Along with the daily reports and schedules published in newspapers such as The Times, this allows a useful comparison with Taylor’s ‘listening-in’ log and shows that while much excitement surrounded the entertainment possibilities of the new medium it was already also being put to many other uses – time signals being regularly transmitted as a means of synchronizing clocks and watches over a wide area and weather forecasts being aired soon after their issue by the met office – a great advantage to mariners who’d hitherto had to rely on newspaper information up to a day old.

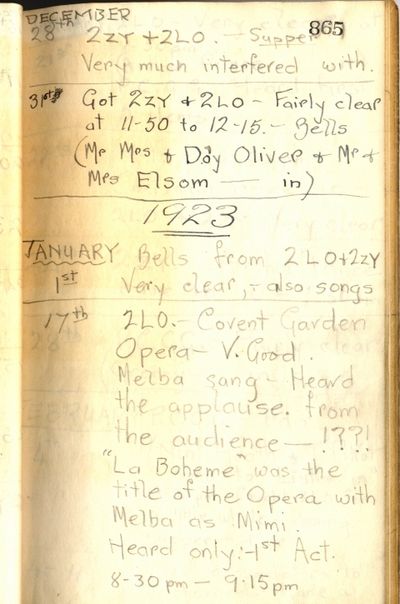

The Wireless Log page 6: 28th Dec 1922 to 17th Jan 1923

On the 28th December 1922 Alfred notes that his reception of 2ZY (BBC Manchester) and 2LO (BBC London) during his radio supper was “very much interfered with” – possibly due to atmospheric conditions but more likely down to the many amateur radio hams, transmitting as well as receiving, who were already starting to crowd the airwaves despite warnings from the Postmaster-General that they should first listen in to their chosen wavelength to ensure that they would not be interfering with other stations.

On the 17th Jan (1923) he also notes the live relay of La bohème from Covent Garden featuring Dame Nellie Melba, already famous for her experimental Chelmsford broadcast of June 1920, but seems more struck by the sound of the concert audience coming directly into the family’s Lincoln home.

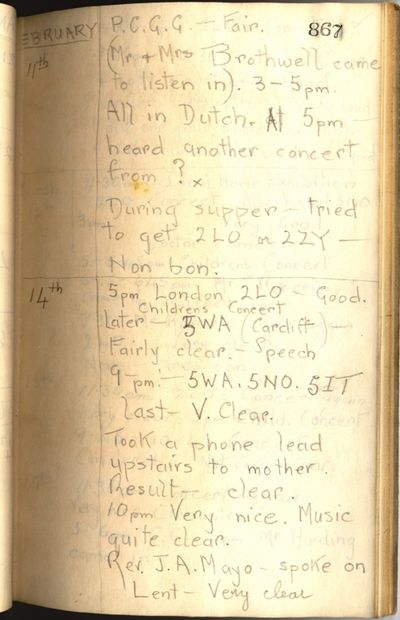

The Wireless Log page 8: 11th-14th February 1923

By February, Taylor was picking up several new BBC stations which had by then launched, including 5WA (Cardiff), 5NO (Newcastle) and 5IT (Birmingham). On the 14th he “Took a phone lead upstairs to mother” – presumably because she was confined to bed – and on the following day experimented with a technique for group listening to a “very loud” recital by the Wireless Orchestra: “Laid one pair phones on table & sat round & listened in – Good”

Although only a handful of radio recordings survive from the 1920s and listening logs of this kind – commencing before the first official day of transmission – must have been rare, many people presumably made single or occasional notes in their diaries concerning the new medium and what they heard. The radio curator would be interested to hear from anyone who has unpublished written records of radio listening in the 1920s and any interesting examples which come to light will be reproduced in a future update to this blog.

N.B. Please do not post any unique materials without first contacting us for advice. Email the radio curator at [email protected] or write to: Paul Wilson, The British Library, 96 Euston Road, London NW1 2DB.