In November 1912, Thomas Edison released what became the last word in mass-produced cylinder technology – his four minute Blue Amberol series. These cylinders started to appear in the United Kingdom in February 1913 although cylinders of various other types had been around for more than twenty years. It’s a common presumption that phonographs were owned only by the rich, but they were mass-produced: in 1913 there were a million cylinder players in use in the United States of America.

What would the soundtrack to Christmas in England have been like one hundred years ago?

It’s December 1913. You step into a shop to buy something for Christmas, something that everyone will enjoy. You’d like to fill your home with the wonder of recorded music.

In August 1913 the magazine The Phono Record reported that war has been declared. The record industry is booming and there are a number of record labels competing for your business: Besttone, Dacapo, Empire, Exo, Mignon, National, Odeon, Pathé, Zonophone and Columbia to name just a few. The gramophone is in fashion, and everyone is telling you that discs are the future, but your mind is made up: you’re buying an Edison cylinder phonograph to play the new Blue Amberols.

Your neighbour upgraded for the similarly named, four minute wax Amberol series about a year ago, but you didn’t fancy those at the time. Even though he says they are the ultimate in cylinder technology, you think they sacrifice sound quality for more playing time; they seem too quiet, wear out quickly and are so incredibly brittle that they often self-destruct while playing. You’re glad you waited patiently for the next format, where wax is swapped for celluloid - he’ll have to re-buy the same releases on Blue Amberol if he wants to get top sound quality.

Listen to the The Singer Was Irish by Peter Dawson, first issued on Black Amberol in November 1910, but recently digitised from a Blue Amberol at the British Library.

The Singer Was Irish (1CYL0001641)

Blue Amberols, even in a hundred years time, will be recognised as having been at the pinnacle of cylinder technology. The old Edison standards (two-minute black wax cylinders) which are still available, are noisy and play for only a little over two minutes. Hear for yourself:

A Christmas Ghost Story (1CYL0002319)

These new ones play for an unbelievable four minutes! Each one is dyed a brilliant blue to lower the surface noise and can be played 3,000 times – they’re "virtually indestructible". In the loudness wars, they win too.

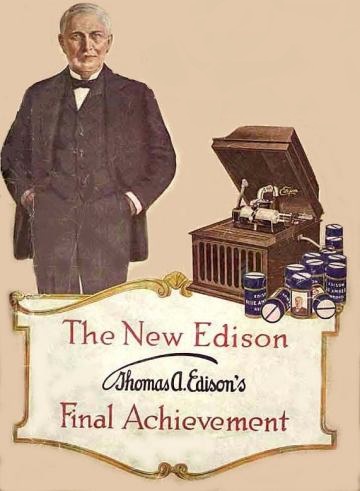

In the shop the assistant has been reading his Edison Phonograph Monthly and is armed with the tactics to relieve you of the £9.9s.0d you’ve saved up. You’ve chosen a nice new Amberola VIII in golden oak which has an internal horn, as do all modern Edison phonographs. Now you just have to choose the cylinder records. The blue cylindrical cartons with Thomas Edison’s face all look the same and each one has a tiny stamp on it – the copyright act came into effect last year.

Edison believes sound quality rather than artist's fame should be the key to selling records, so they don’t feature heavily on the packaging. There is a mere mention on the lid and a category - ‘Christmas song’ or 'Bell solo' - however, on the record slip inside the carton, there is much written about composers and an "if you liked this then you’ll like that" recommendation.

Waltzing Doll (1CYL0000039)

The assistant allows you to try out some of the records available on the lists before you make your purchase. The current catalogue is made up of sentimental American releases and instrumental ‘solos’ – bells, whistling and other instruments with an orchestral backing. These are for the most part recorded at Edison’s studio in New Jersey, but there’s also a small selection of English special releases - about fifteen on each month’s list. Speeches and extracts from books, and even a ‘School’ series with titles such as ‘Ten problems in measurements’ are also available.

Choose carefully - within the year war will be declared, and the list will be taken over by patriotic songs and forget-there’s-a-war-on specials. In October 1914 war-time legislation will impose a tax of 33.3% on both cylinder players and records and by 21 March 1916 you won’t be able to buy any of the latest New Jersey-made records due to the import ban on cylinder players and records.

Here’s a selection of releases that were available in December 1913:

From the English list -

Christmas At Sea (1CYL0001641)

Blue Amberol 23150 Christmas at Sea, National Military Band. Recorded in London; available only on Blue Amberol.

Sweet Christmas Bells (1CYL0001648)

Blue Amberol 23143 Sweet Christmas Bells (Shattuck), Ernest Pike and Peter Dawson. Originally released on (wax) Amberol 12100; recorded in London, December 1909.

Why Don't Santa Claus Bring Something To Me? (1CYL0002080)

Blue Amberol 23146 Why Don’t Santa Claus Bring Something To Me? (Williams / Godfrey), Billy Williams. Originally released on (wax) Amberol 12499; recorded in London, October 1912.

Scrooge's Awakening (1CYL0001205)

Blue Amberol 23139 Scrooge’s Awakening (Dickens – A Christmas Carol), Bransby Williams and Edison Carol Singers. Originally released on (wax) Amberol 12378; recorded in London, December 1911.

From the American list -

When I Get You Alone Tonight (1CYL0001245)

Blue Amberol 1602 When I Get You Alone Tonight (McCarthy /Goodwin / Fisher), Billy Murray. Recorded in New York, October 1912.

Jere Sandford's Whistling and Yodeling Special (1CYL0001259)

Blue Amberol 1988 Jere Sanford’s Whistling and Yodeling Special. Originally released (wax) Amberol 523; recorded in New York, October 1910.

Dixie Medley (1CYL0000366)

Blue Amberol 1532 Dixie Medley, Fred Van Eps. Originally released on (wax) Amberol 4M 804; recorded in New York, October 1911.

Blue Amberol cylinders are one of the many audio formats digitised at the British Library Centre for Conservation. This is done through a one-of-a-kind electrical cylinder player (similar to a record player) but in 1913 they would have been played back on a wind-up phonograph. Phonographs acoustically amplify, through a horn, vibrations caused in a diaphragm made by the movement of a stylus through a groove. The records played on them were recorded in the same way: microphones did not come into use in recording studios until the 1920's.

You can listen to more wax cylinders in British Library Reading Rooms by browsing the the Sound and Moving Image Catalogue between call numbers 1CYL0000001 and 1CYL0003000. The British Library's collection of ethnographic wax cylinders is available to listeners online.

Written by sound engineer Eve Anderson who is currently digitising wax cylinders at the British Library.