The bicentenary of the battle of Waterloo is upon us, and of the many books, programmes and articles currently published about the event, one of the most novel and fasincating is Brian Cathcart's history The News from Waterloo. This tells not the story of the battle but of the race to report the news in Britain, and in doing so it tells us a lot about the transmission and understanding of news in the past, and the world of news we enjoy today.

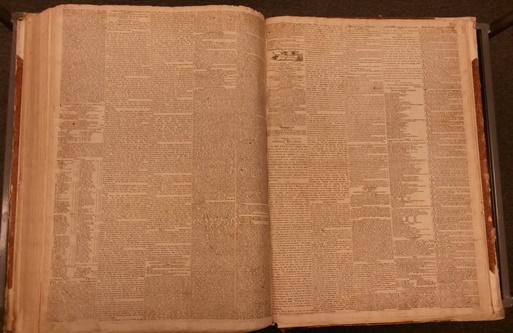

The 11:00 am 'Waterloo' edition of The Times, 22 June 1815.

The battle itself took place on Sunday 18 June 1815, ending somewhere between 9 and 10 that evening. The British public, however, did not start to receive certain news of the outcome of the battle (nor indeed confirmation that any such battle had taken place) until the very end of Wednesday 21 June, with the London newspapers reporting the story from the morning of the 22nd.

The reasons for this delay were several, and in describing them Cathcart gives an excellent and accessible account of how newspapers operated in the early nineteenth century. To begin with, there were no journalists at Waterloo. Newspapers in Britain at that time did not have journalists as we would understand them; there were parliamentary reporters (a recent innovation after government had finally conceded to the reporting of its affairs), there was an editor who would write the editorial, and there was much gathering of content from other sources, such as official sources - foreign news was generally channeled through the Post Office, as a means of exercising governmental control over reporting such dangerous information.

Government exercised control over newspapers through law (particularly libel laws) and through taxation, which had the effect of narrowing down the number of people who might read a newspaper because of the cost, and hopefully keeping the news out of the hands of the masses. This only worked so far, because newspapers were nevertheless distributed widely, borrowed, made available in reading rooms, inns and coffee houses, and read aloud in groups. But the high cost meant a restricted buying public, and together with the mechanical limitations of newspaper production of the time kept down the number of copies published - The Times sold around 7,000 copies a day in 1815.

News travelled slowly, though it was speeding up. The mechanical or optical telegraph, which worked by replaying signals from high vantage points, meant that messages could travel quickly over long distances, and it awakened in people a sense of news being able to be communicated to them far more quickly. However, the telegraph was expensive to maintain and it didn't work in the dark. Extraordinarily such problems led to the British closing down their telegraph operation shortly before Waterloo, so the only way to get the news to the British public was by road and water.

Cathcart's book entertainingly describes how news false and true made its way to London from Waterloo, causing much confusion among a public desperate to know if Napoleon had been defeated, as accounts of the battles that took place the day before Waterloo were muddled up with the battle on the 28th, communicated by private individuals who brought over scraps of information on what they thought had happened. (See his blog post for the British Newspaper Archive for a summary of these unofficial reports.) The official dispatch, which Wellington completed writing around noon on June 23, was mysteriously delayed while its bearer, Major Henry Percy, was travelling through the Netherlands. It then got held up crossing the Channel when the wind dropped, so that Percy ended up having to get into a rowing boat, before completing his journey by post-chaise. Finally the official dispatch was delivered in London around 11:15 pm on Wednesday 21 June, not a moment too soon for the newspapers laboriously to remake some type and to publish an account for the morning editions.

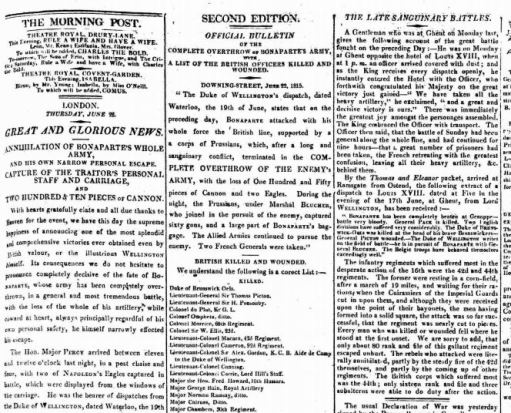

The Morning Post, 22 June 1815, via British Newspaper Archive (note that it is the second edition)

There were an estimated 56 newspapers published in London at this time, from dailies to weeklies. The leading titles were The Times, The Courier, The Morning Post and The Morning Chronicle. This was a time before there were press directories with lists of all newspaper titles published, but in the British Library collection we have just under 300 British newspaper titles from 1815, with some 40 of them published in London. So it is not every newspaper that was published. Cathcart has done a remarkable job piecing together the complex narrative of what was published when over 18-22 June 1815, noting where a newspaper issued more than one edition with more war information, but bemoaning the fact (on his website) that "Superb though it is, the British Library collection is nothing like complete for 1815." Well, there's a reason for that.

In 1815 there was no national newspaper collection. The Stamp Office took in a copy of every newspaper published (part of the taxation regime designed to keep the newspapers in line), retaining these for a period of two years before disposing of them. It was only in 1823 that copies published in London started to be transferred to the British Museum, with regional newspapers following after 1832, and not until 1869 were newspaper deposited directly with the Museum.

So for newspapers in 1815 we are dependent on private collections acquired subsequently, and inevitably there are gaps in the surviving record. Moreover, the British Museum and then the British Library have always collected just one edition of a newspaper per day, for practical reasons of space. We do not have, and cannot have, everything. Different editions of an historical newspaper on a single day are therefore quite a rarity (indeed most titles in 1815 only produced a single edition), existing usually on the few occasions where the same title was acquired from different collectors.

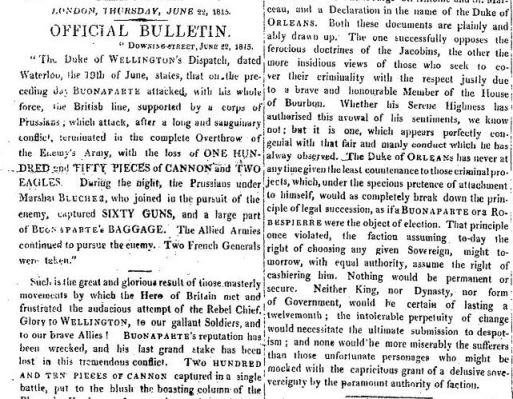

From page 3 of The Times, 22 June 1815, via The Times Digital Archive, summarising information on Waterloo learned from the official dispatch.

Fortunately 22 June 1815 is one date when there are some different timed editions available. The early edition of The Times for that day had the above notice, noting that the official dispatch had been received and summarising its contents. It is this version of the newspaper that can be found online via the Times Digital Archive (subscription access only, freely available in British Library reading rooms). The copy in the British Library is of the second edition, issued at 11:00 am that day. For this the second page of the 4-page newspaper had been entirely remade to accommodate the Duke of Wellington's complete dispatch. The full two pages are illustrated at the top of this post; the start of dispatch on page 2 is below, alongside the earlier page 2 from the version on the Times Digital Archive:

From page 2 of the The Times, 22 June 1815, early morning edition on left (via Times Digital Archive), 11:00 am edition on the right (from British Library collection), with the official dispatch from Waterloo reproduced on the right-hand column.

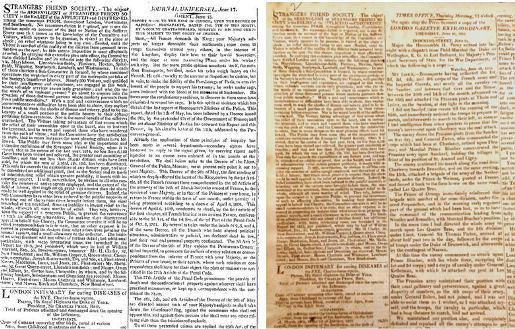

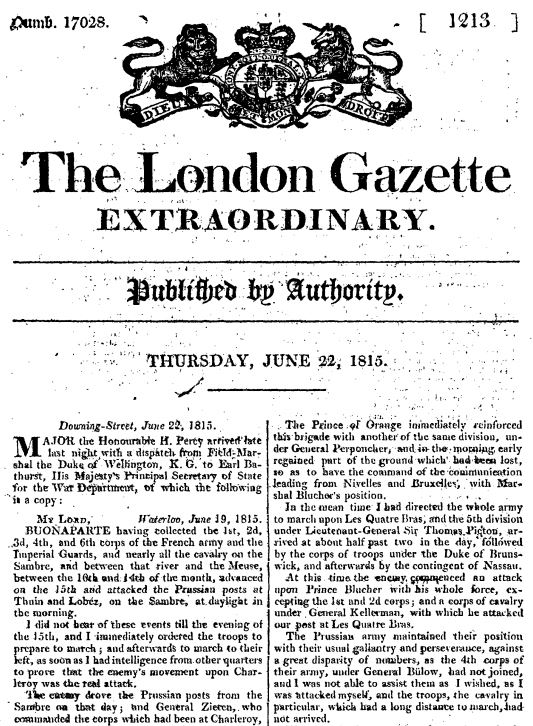

The dispatch had first been published in The London Gazette, which was a government publication issuing official information, and which is still in operation today (as The Gazette). The Waterloo 'extraordinary' edition of The London Gazette is freely available online, and this is the front page:

The London Gazette, 22 June 1815, via www.thegazette.co.uk. Wellington's official dispatch did not reveal the information that the battle had been won until halfway down the second column of the second page.

Once The London Gazette had been published, the other London newspapers plundered the official text for their own editions, and then gradually the information spread over the nation as mail coaches carried the news to every corner over the next few days (Edinburgh, for example, received the information on Saturday 24 June).

Today we may marvel at a time when the news of a major battle took three days to get from Waterloo to London, with part of the journey undertaken by rowing boat. We live in a world of constantly breaking news, where tweets or other electronic alerts informs us of news happening even before it is news (if we define news as something which has been composed after a period of time with an understanding of the context of the story, and with checks made to verify it). News has become instantaneous. Moreover news is cheap, for the most part free (in the UK) from governmental interference, and created by legions of journalists.

Yet in some ways the news archive we are creating for 2015 will be as problematic for future historians as 1815 is for us today. We are not keeping every edition of every newspaper published on any one day. More than that the news has now spread over so many different media and platforms that it lies beyond anyone's ability to capture it all. Still more problematically, we are failing to capture the experience of news today. Increasingly we are finding our news online, but web archives can only operate as snapshots, capturing how a web pages looked at a particular point in time.

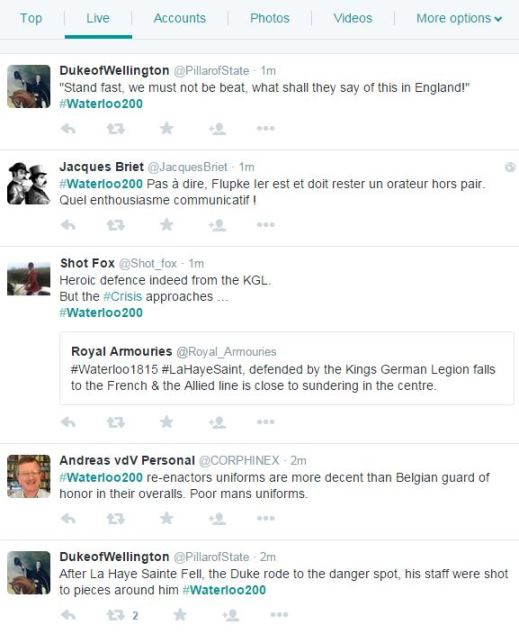

Most of the websites that we archive are crawled just once a year, but for news websites we archive these on a daily or weekly basis. Yet not only will stories fall between the cracks (i.e. they may disappear from a site between one archive capture and the next), but the experience of the flow of news is lost. There is nothing in web archiving - as yet - that can capture the experience of seeing news being reported as it happens, as we experience through ever-changing Twitter feeds or through the increasingly-popular live blogs on news websites (and the British Library does not currently archive social media, except on a very selective basis). News is increasingly tailored to our individual interests - we may each of us see a different news. News is now an endless succession of ever-changing editions; but as archivists we still capture it as a single instance, as though it were still a thing on paper, to be published just once a day.

The endless flow of news - the live #Waterloo200 Twitter feed at 18:36, 18 June 2015

In 1815 we see the news almost overwhelming the mechanisms that were put in place to communicate it. The need to know outstripped the means to satisfy it. That led to new technologies. In 1814 The Times had introduced a steam-driven press, which would transform the rate at which newspapers could be printed. The arrival of the railways greatly spread how newspapers could be distributed, and the electric telegraph (the first working system of which was demonstrated in 1816) collapsed the distances between places worldwide. The invention of steam ships put an end to becalmed sailing ships holding up the news from overseas.

In 2015 we again see the overwhelming nature of the news. There is so much news available that services like Facebook must now filter it for us, telling us what they think we need to know. We cannot capture everything, yet we must strive always to capture something, and trust in the ingenuity of historians such as Brian Cathcart to fill in the gaps in the archive as they find it. History is not made by the evidence; it is a product of the reasoned imagination.

Where to find British newspapers from 1815:

- British Library - most surviving British newspapers for 1815 are held by the British Library and can be accessed by anyone with a Reader's pass at either of our sites (St Pancras, London and Boston Spa, Yorkshire)

- British Newspaper Archive - the subscription website based on digitised newspapers from the British Library's collection has 48 titles for 1815, four of them London titles (Morning Chronicle, Morning Post, The Examiner, Cobbett's Weekly Political Register)

- The Gazette - the full run of the London Gazette from 1665 (when it was the Oxford Gazette) to the present day can be found for free on its site

- Guardian and Observer Digital Archive - subscription site - only The Observer was published in 1815

- Newspaperarchive.com - American subscription site with some British titles covering the 1810s

- Times Digital Archive - subscription site for The Times, from 1785 to 2009