There are now two curators called Alex in the Modern Manuscripts and Archives department here at the British Library. One of us is a political historian looking after manuscripts from 1851-1950, the other is an art historian working with manuscripts between 1601-1850. We both get called 'The Other Alex' when colleagues are trying to differentiate between us.

Despite our historical leanings and the difficulties choosing just one item from our Manuscripts Collection to celebrate #NationalPoetryDay, we decided that as we both adore Samuel Taylor Coleridge's (1772-1834) Kubla Khan we would write a joint post about it.

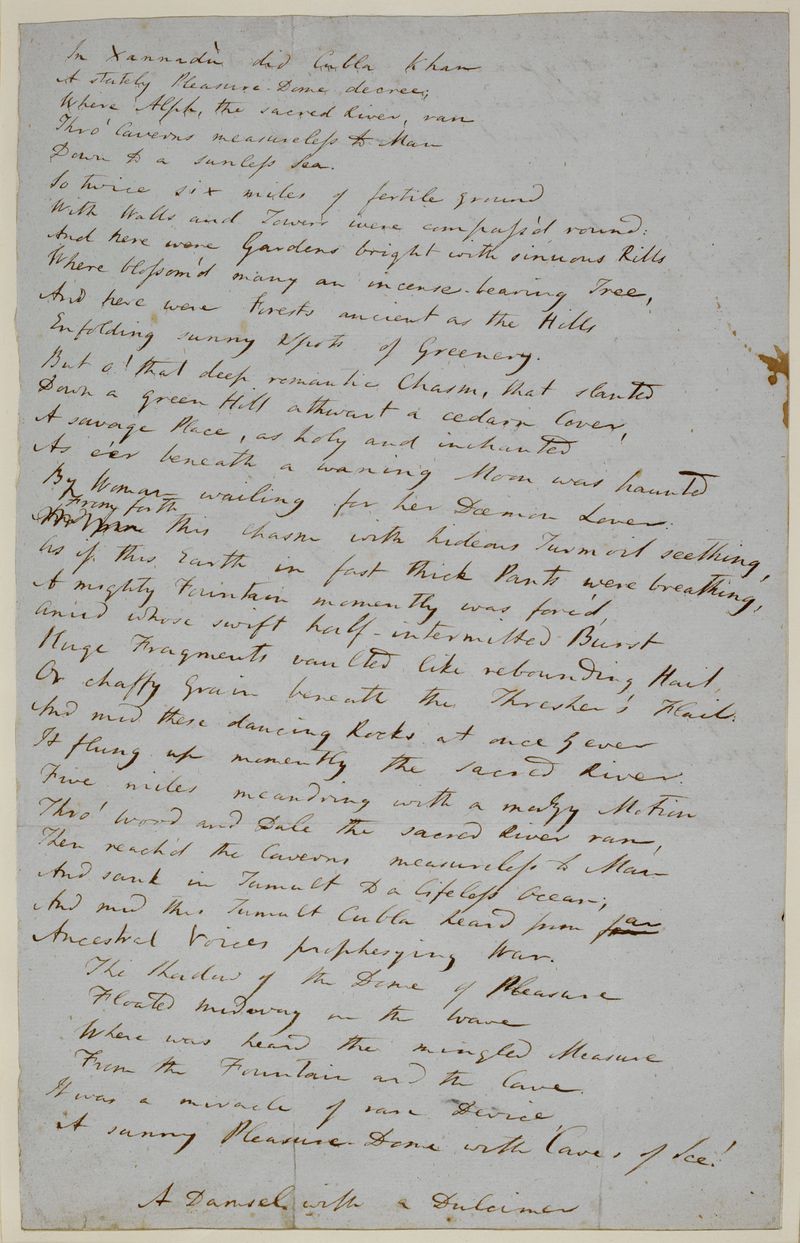

Add MS 50847 Fair Copy Manuscript of Kubla Khan by Samuel Taylor Coleridge 1797-1804.

In 1797 Coleridge was staying at Nether Stowey in Somerset near to his friends William and Dorothy Wordsworth with whom he took frequent walking tours in the surrounding countryside of the Quantocks. According to Coleridge in the published preface to the poem, it was during this time that he composed Kubla Khan. Whilst staying in a ‘lonely farm house between Porlock and Linton’ he took two grains of opium and fell asleep ‘in his chair’ while reading a copy of Purchas His Pilgrimage (1625). This four-volume compilation of travel narratives was written by the English clergyman Samuel Purchas (1577-1626) and contained historical, religious and geographical descriptions of China including Xandu, the summer palace of the great Chinese Emperor and Mogol ruler, Kublai Khan (1215-1294). Purchas described Xandu as:

‘A marvellous and artificial Palace of Marble and other stones… In this inclosure or Parke are goodly Meadowes, springs, rivers, red and fallow Deere, Fawnes carried thither for the Hawkes… In the middest in a faire Wood hee hath built a royall House on pillars gilded and varnished, on every of which is a Dragon all gilt’.

According to Coleridge, these passages on Xandu inspired the vivid opium dream that followed and that would go on to form the basis of his poem. As he recollected in his preface, ‘he was reading the following sentence, or words of the same substance, in 'Purchas's Pilgrimes': 'Here the Khan Kubla commanded a palace to be built, and a stately garden thereunto: and thus ten miles of fertile ground were inclosed with a wall.'

Upon waking, he ‘instantly and eagerly wrote down the lines’ that were inspired by the dream:

‘In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.’

Before he was able to finish the poem, Coleridge was interrupted ‘by a person on business from Porlock’ and when he returned to his room his visions had ‘passed away like the images on the surface of a stream into which a stone had been cast’. Clearly, the opium had worn off. As a result the poem remains an unfinished fragment but it is sumptuously rich in its language, meter, and imagery.

Sadly, we don’t own the original manuscript that Coleridge wrote in his opium induced reverie, but the British Library does hold an early fair copy (a neat copy) of the manuscript containing some corrections and later revisions. Coleridge wrote this on two sides of blue-tinted paper, in preparation for sending to the printer. On the manuscript, beneath the poem, Coleridge has described how the poem came into being:

“This fragment with a good deal more, not recoverable, composed, in a sort of Reverie brought on by two grains of Opium, taken to check a dysentery, at a Farm House between Porlock and Linton, a quarter of a mile from Culbone Church, in the fall of the year, 1797. S.T. Coleridge.”

Although Coleridge recited the poem in the presence of friends on several occasions, he did not publish it until nearly 20 years after its composition. It was Lord Byron who encouraged Coleridge in its publication and it was finally included in Poems (1816), in which Coleridge referred to it as ‘a psychological curiosity’. Despite taking so long to come to press, it has nevertheless become one of the nation’s favorite poems and we in the manuscripts department are very privileged to care for this unique document.

The British Library has an exciting and extensive collection of manuscripts by important British poets many of which have been digitised and include works by John Keats, William Wordsworth, Alfred Lord Tennyson and Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Alexander Lock, Curator, Modern Historical Manuscripts and Archives 1851-1950

Alexandra Ault, Curator, Modern Historical Manuscripts and Archives 1601-1850