Since the passing of Legal Deposit legislation in April of 2013 the UK Web Archive has been generating screenshots of the front-pages of each visited website. The manner in which we chose to store these has changed over the course of our activities, from simple JPEG files on disk (a silly idea) to HAR-based records with WARC metadata records (hopefully a less silly idea). What follows is our reasoning behind these choices.

What not to do

When Legal Deposit legislation passed in April of 2013 we were experimenting with the asynchronous rendering of web pages in a headless browser (specifically PhantomJS) to avoid some of the limitations we’d encountered with our crawler software. While doing so it occurred to us that if we were taking the time to actually render a page in a browser, why not generate and store screenshots?

As we had no particular use-case in mind they were simply stored in a flat file system, the filename being the Epoch time at which they were rendered, e.g:

13699895733441.jpg

There’s an obvious flaw here: the complete lack of any detail as to the provenance of the image. Unfortunately that wasn’t quite obvious enough and after approximately 15 weeks and 1,118,904 screenshots we changed the naming scheme to something more useful, e.g:

http%3A%2F%2Fwww.bl.uk%2F_1365759028.jpg

The above now includes the encoded URL and the epoch timestamp. This was again changed one final time, replacing the epoch timestamp with a human-readable version, e.g:

http%3A%2F%2Fwww.bl.uk%2F_20130604121723.jpg

Despite a more sensible naming convention we were still left with a large number of files sitting in a directory on disk which could not be stored along with our crawled content and as a consequence of this, could not be accessed by normal channels.

A bit better?

A simple solution was to store the images in WARC files (ISO 28500—the current de facto storage format for web archives). We could then permanently archive them alongside our regular web content and access them in a similar fashion. However, the WARC format is designed specifically for storing web content, i.e. a resource referenced by a URL. Our screenshots, unfortunately, didn’t really fit this pattern. Each represented the Webkit rendering of a web page, actually likely to be the result of any number of web resources, not just the single HTML page referenced by the site’s root URL. We therefore did what anyone does when faced with a conundrum of sufficient brevity: we took to Twitter.

The WARC format contains several types of record which we potentially could have used: response, resource, conversion and metadata. The resource and response record types are intended to store the “output of a URI-addressable service” (thanks, @gojomo). Although our screenshots are actually rendered using a webservice, the URI used to generate them would not necessarily correspond to that of the original site, thus losing the relationship between the site and the image. We could have used a further metadata record to tie the two together but others (thanks to @tef and @junklight) had already suggested that a metadata record might be the best location for the screenshots themselves. Bowing to conventional wisdom, we opted for this latter method.

WARC-type: metadata

As mentioned earlier, screenshots are actually rendered using a PhantomJS-based webservice —the same webservice used to extract links from the rendered page. It is at this point worth noting that when rendering a page and outputting details of all requests/responses made/received during said rendering, PhantomJS by default returns this information in HTTP Archive (HAR) format. Although not specifically a formal standard, HAR has become the almost de facto method for communicating HTTP transaction information (most browsers will export data about a page in this format).

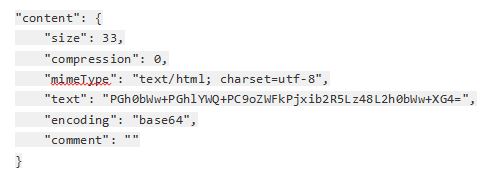

The HAR format permits information to be communicated not only about the page, but about each of the component resources used to create that page (i.e. the stylesheets, Javascript, images, etc.). As part of each response entry—each pertaining to one of the aforementioned resources—the HAR format allows you to store the actual content of that response in a “text” field, e.g:

Unfortunately, this is where the HAR format doesn't quite meet our needs. Rather than storing the content for a particular resource we need to store content for the rendered page—potentially the result of several resources and thus not suited to a response record.

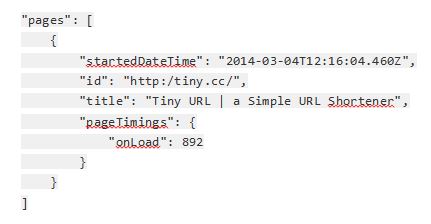

Thankfully though, the HAR format does permit you to record information at a page level:

Better still…

Given the above we decided to leverage the HAR format by combining elements from the content section of the response with those of the page. There were two things we realised we could store:

1. As initially desired, an image of the rendered page.

2. The final DOM of the rendered page.

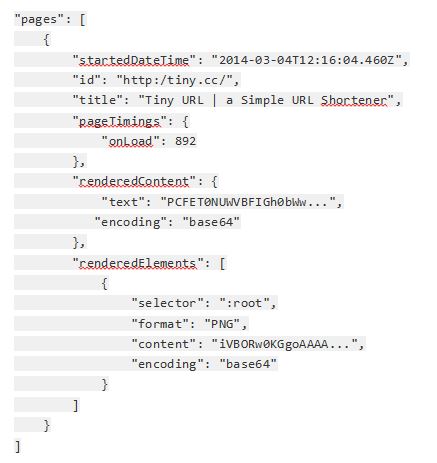

With this latter addition, it occured to us that the final representation of a HTML page—thanks to client-side Javascript altering the DOM—might differ from that which the server originally returned. As this final representation was the version which PhantomJS used to render the screenshot it made sense to attempt to record that too. In order to distinguish this final, rendered version from content of the HAR’s corresponding response record the name was amended to renderedContent.

Similarly named, we stored the screenshot of the whole, rendered page under a new element, renderedElements:

‘renderedElements’?

Given that we were trying to store a single screenshot, storing it in an element which is firstly, plural and secondly, an array, might seem a questionable choice. PhantomJS has one further ability that we decided to leverage for future use: the ability to render images of specific elements within a page.

In the course of a crawl there are some things we can't (yet) archive—videos, embedded maps, etc. However, if we can identify the presence of some non-archivable section of a page (an iframe which references a Google Map, for instance), we can at least render an image of it for later reference.

For this reason, the whole-page screenshot is simply referenced by its CSS selector (“:root”), enabling us to include a further series of images for any part of the page.

About those jpgs…

Currently, all screenshots are stored in the above format, in WARCs and will be ingested alongside regularly-crawled data. The older set of JPEGs on disk were converted, using the URL and timestamp in the filename, to the above HAR-like format (obviously lacking details of other resources and the final DOM which had been lost) and added to a series of WARC files.

The very earliest set of images, those simply stored using the Epoch time, are regrettably left as an exercise for future workers in Digital Preservation.

by Roger G. Coram, Web Crawl Engineer, The British Library