The first page of the prologue, with decorated initial P and foliate border; from Ranulf Higden, Polychronicon, England, 3rd quarter of the 15th century, Harley 3877, f. 9r.

Ranulf Higden (d. 1364) was a Benedictine monk famous for writing the Polychronicon, a universal chronicle of world history. Finished originally in 1340, it was continued throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, both by Higden and other writers. The Polychronicon was extremely popular, and is now extant in over 100 manuscripts. Even during Higden's lifetime, in 1352, King Edward III requested that the author come to court, bringing his chronicle with him.

Higden's work is encyclopaedic, incorporating descriptions not just of historic events, but of customs, natural history and geography. In some manuscripts this included a map of the world. The one in Royal 14 C. ix is an early and elaborate example that may closely reflect Higden's original version. As was the traditional medieval form for such maps, Jerusalem is in the centre, with Paradise above, in the east. Britain (shown here in red and labelled 'Anglia') is to the lower left, at the very edge of the known world.

Map of the world with east at the top; from Ranulf Higden, Polychronicon, England, last quarter of the 14th century, Royal 14 C. ix, ff. 1v-2r.

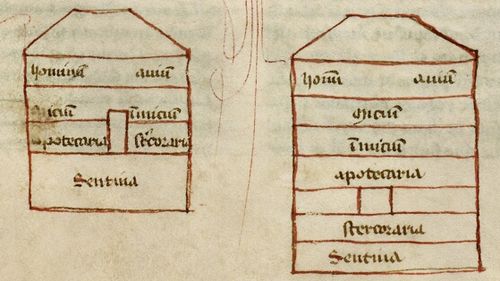

While Higden is termed the 'author' of the Polychronicon, it is not all his original prose. Instead, he brought together a variety of authorities, compiling excerpts, anecdotes and explanations from previous histories. This technique is visually evident in the diagrams of Noah's ark. Its relatively precise description in the Bible has long prompted attempts to portray the ark's exact dimensions and layout. Polychronicon manuscripts frequently include two diagrams, side-by side, one with the plan as described by Augustine, and a competing version drawn from other authorities. Both plans show areas reserved for 'men' (upper left) and 'birds' (upper right), as well as for 'gentle' and 'ungentle' animals (herbivores and carnivores, housed separately, for obvious reasons). Further down are an area for supplies and, at the very bottom, the bilge. The picture even answers the question that has occurred to many a child on hearing about the ark: where did they go to the bathroom? One section on each diagram is labelled 'Stercoraria', or 'privy'.

Detail of two diagrams of Noah's ark, labelled with the functions of the different parts of the ship; from Ranulf Higden, Polychronicon, England, 2nd quarter of the 15th century, Harley 1728, f. 47r.

Higden's chronicle provides a window onto the interests of medieval historians (and medieval readers of history), and comparing different manuscripts offers insight into how he organized the whole knowledge about the world. The Polychronicon includes a number of aids for breaking it down into manageable units. An alphabetical index is a common feature of Polychronicon manuscripts, listing the book and chapter number reference for characters from Abraham to Zorobabel.

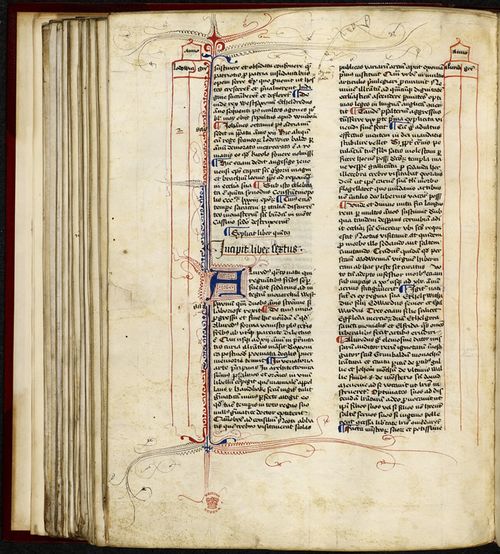

The beginning of Book VI, with two marginal columns prepared for recording the year, dating both from the birth of Jesus and within the reigns of Louis II (left) and Alfred (right); from Ranulf Higden, Polychronicon, England, c. 1445, Harley 3884, f. 118v.

Also interesting is the treatment of dates. Many of the manuscripts keep track of the relative chronology of events by noting dates in the margins, alongside the text. These dates were even provided on pages where none appeared, by running headings at the top of the page. Harley 3884 has an elaborate example of this system, with red columns running down the page. Above are headings labelling the columns by the year 'of grace' (the number of years since the birth of Jesus, roughly equivalent to our modern dating CE) and the dating according to important people. On this page, the left column records the regnal year of the 9th-century Louis the Stammerer, and that on the right the regnal year of the West Saxon King Alfred.

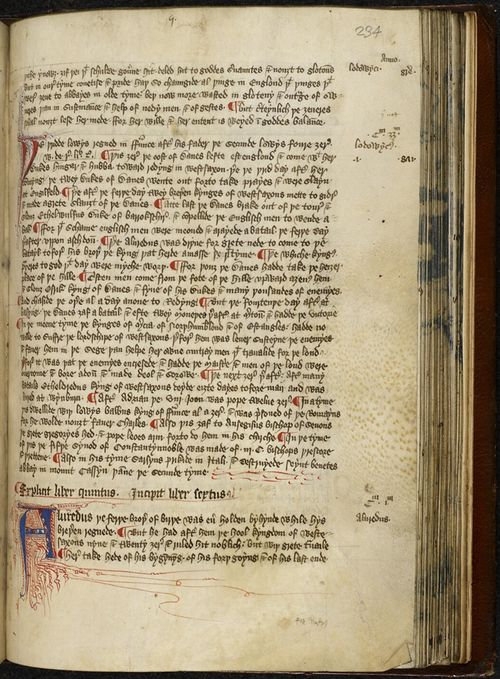

The consistency in presenting these dates indicates that they were formed an intergral part of the Polychronicon's organization. This consistency even crossed linguistic lines. John Trevisa made an English translation of Higden’s work, completed around 1387. On the page below, from an early 15th century manuscript, are the same headings for the year 'of grace' and regnal date of Louis (though without the red columns). Polychronicon manuscripts vary in quality, but all, from the most haphazard to the most deluxe, are influenced by the same impulse toward organizing history and knowledge about the world.

The beginning of Book VI, with a right margin containing chapter numbers, the names 'lodowycus' and 'Alvredus', and dates; from Ranulf Higden, Polychronicon, translated by John Trevisa, England, last quarter of the 15th century, Harley 1900, f. 234r.