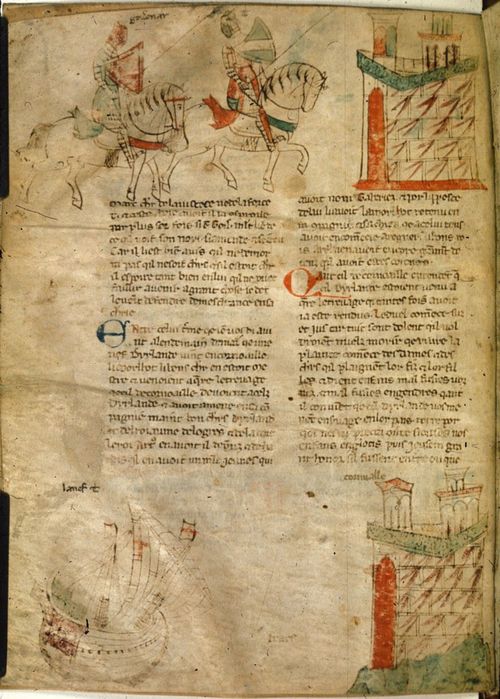

Miniatures of (above) Tristan and his mentor arriving at a castle and (below) Tristan arriving in Cornwall by ship; from Roman de Tristan en prose, last quarter of the 13th century or first quarter of the 14th century, Italy (Genoa), Harley MS 4389, f. 15v.

Tristan and Isolde are two of the great lovers of medieval

literature, and their doomed affair was retold in several different versions. The

British Library's Harley MS 4389 contains an incomplete copy of the Roman de Tristan in French prose, enlivened

by a large number of coloured drawings illustrating the story. They are not

the highly finished productions of elite illuminators, but nevertheless they

hold tremendous appeal.

The overall impression given by these pictures is of

movement and dynamism. The most common subjects are battles (between two

knights or as part of a chaotic mêlée) and travel. Ships recur again and again:

carrying passengers, approaching castles, even standing in the background of a

combat. In one stretch of six consecutive miniatures, only one does not contain

a ship. The visual emphasis on Tristan's travel transforms him into an

itinerant figure, wandering through the world of Cornwall,

Ireland and Gaul.

Detail of a miniature of Tristan (left) fighting Morholt; from Roman de Tristan en prose, last quarter of the 13th century or first quarter of the 14th century, Italy (Genoa), Harley MS 4389, f. 18v.

The drawings are sometimes simple and formulaic,

particularly when depicting battles between knights. The repetition creates a visual

continuity, as knights travel by ship through a landscape dotted with

opportunities for combat. But the illustrations do not wholly eschew the

specific, and some are immediately identifiable. Below, for example, is the

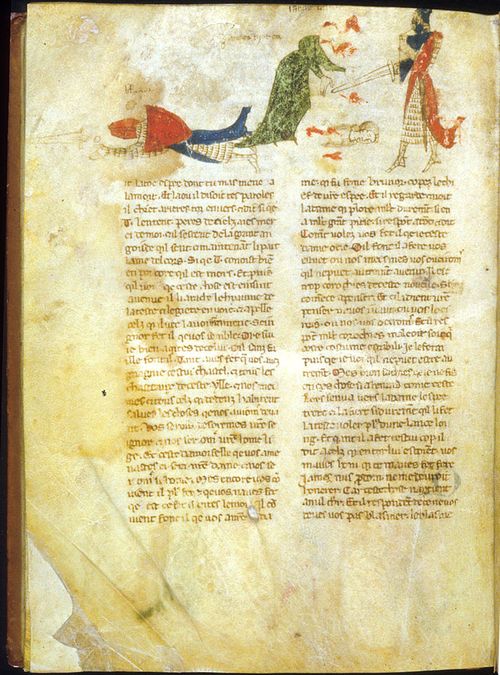

story of Tristan's birth. Tristan's parents were also ill-fated lovers: when

his father's kingdom was attacked, his mother fled in secret. Their story ended

with the king killed in battle, and the queen dead in childbirth. In this

picture, Tristan's mother lies dead in a field, and her waiting woman, holding

the infant Tristan, has been found by two knights who will take him to be

raised in exile by loyal retainers.

Detail of a miniature of the death of Tristan's mother; from Roman de Tristan en prose, last quarter of the 13th century or first quarter of the 14th century, Italy (Genoa), Harley MS 4389, f. 5r.

The best-known part of Tristan's story, in the Middle Ages

as well as today, was his love for Isolde. Tristan had been sent to Ireland

to retrieve the princess Isolde, his uncle King Mark's betrothed. On the way

back, the two fell in love when they unwittingly drank a love potion intended

for Isolde to share with her future husband. Their subsequent clandestine

affair became a source of great tension between Tristan and his uncle, who

suspected the truth and periodically plotted against Tristan, the most skilled

knight in his court.

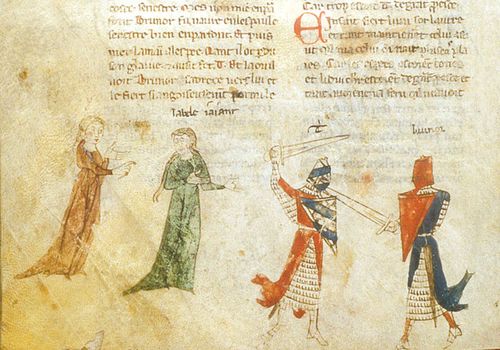

Detail of a miniature of Isolde (far left, in a rare appearance) and the Beautiful Giantess, watching the duel between Tristan and Brunor (far right); from Roman de Tristan en prose, last quarter of the 13th century or first quarter of the 14th century, Italy (Genoa), Harley MS 4389, f. 59v.

In the illustrations of Harley 4389, however, this iconic

affair is given very little attention. Isolde appears only rarely, even as

other women are given greater attention. Two miniatures, for example, are

devoted to the story of the Beautiful Giantess. Tristan and Isolde have travelled

to a country where it is the custom that the lord, Brunor, cut off the head of

any lady less beautiful than his own love, the Beautiful Giantess. Tristan kills

Brunor, but afterwards the people demand that he uphold custom and decapitate

the Beautiful Giantess, as Tristan showed himself the stronger knight and all

agree Isolde is the more beautiful lady. Tristan does not wish to, but, when

threatened with his own death, complies. The illustrators' choice of what to

draw, and what not to, creates a distinct reading of the text.

Detail of Brunor lying dead while Tristan decapitates the Beautiful Giantess; from Roman de Tristan en prose, last quarter of the 13th century or first quarter of the 14th century, Italy (Genoa), Harley MS 4389, f. 60v.

Nicole Eddy