Career options for medieval women were limited. If they were lucky they could choose between getting married or entering a convent. For some, the latter was preferable to becoming a wife, who was often treated as little more than one of her husband’s possessions. The majority of women, of course, still chose marriage and family, and the important question was: what type of man made the best husband? There is a tradition of love debates in courtly society in Anglo-Norman England, which can be found in La Geste de Blanchflour e de Florence and Melior e Ydoine, both based on Latin poems about the relative merits of knights or clerks as husbands. In other words, should you go for brawn or brains? Perhaps the first place to look for an answer to these questions is the Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts, where we searched under ‘clerk’ and ‘knight’ and found some interesting images on the subject.

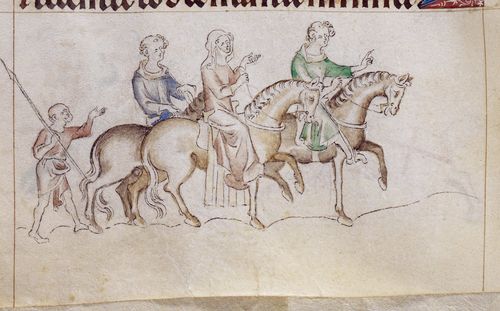

The one below shows a man, described as a ‘devoted clerk from Pisa’ riding with his future wife to their wedding. He appears a good husband, perhaps, if a tad boring (but maybe not – keep reading!).

Detail of a bas-de-page scene of a clerk from Pisa and a woman, being led on horseback to their wedding ceremony, from the Queen Mary Psalter, England (London/Westminster or East Anglia?), between 1310 and 1320, Royal MS 2 B VII, f. 223v

In the next image the clerk has deserted his wife - the Virgin Mary appeared at his wedding and reminded him of his promise to take holy orders!

Detail of a bas-de-page of the devoted clerk of Pisa, having left his bride to become a monk, from the Queen Mary Psalter, Royal MS 2 B VII, f. 224r

Below another clerk seems to be behaving badly. On the left hand side, he grabs a woman, who looks rather startled and on the right he attacks someone, perhaps a rival.

Detail of a miniature of a clerk and a woman, and the clerk committing a homicide, with a foliate initial 'Sacerdos', at the beginning of causa 15 of Gratian’s Decretum, France (Paris?), 3rd quarter of the 13th century, Royal 10 D VIII, f. 176r

So let’s see what the knights were like…

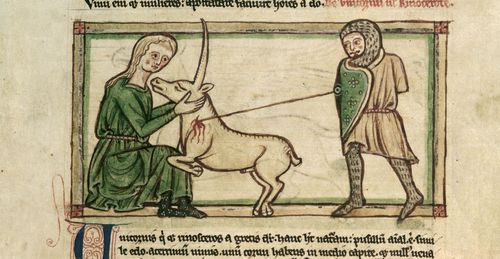

This one is stabbing a unicorn; not a good start!

Detail of the lower miniature, depicting a knight spearing a unicorn as it rests in a maiden's lap, from a theological miscellany, England, 2nd or 3rd quarter of the 13th century, after c. 1236, Harley MS 3244, f. 38r

And this one seems to be offering the lady a lift on his horse, but is he planning to carry her off?

Detail of a bas-de-page scene of a lady and a knight, who is pointing towards his waiting horse; two hounds stand nearby, from the Smithfield Decretals, France (Toulouse?), Royal MS 10 E IV, f. 86v

So, what was a poor girl to do? The answer is, ask her mother for advice.

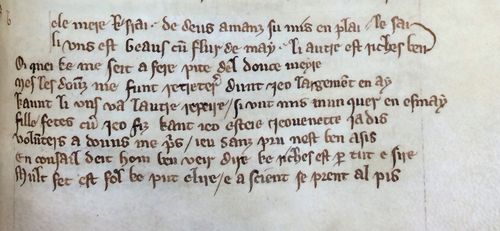

Fortunately, one of our manuscripts, Additional MS 46919, a well-known collection of texts in Anglo-Norman French and Middle English from the 14th century, contains a unique copy of a verse debate between a mother and daughter on choosing a husband. The volume, which has (unfortunately) not been fully photographed yet, is known as the ‘William Herebert Collection’ after the Franciscan friar of Oxford, who compiled it and copied some of the texts, which include Bibbesworth’s Tretiz de langage.

Detail of the beginning of a dialogue between mother and daughter, Add MS 46919, f. 59r

The short debate beginning on f. 59r of this manuscript consists of five 10-line verses alternating between mother and daughter. In the first verse, the daughter asks her mother how she should choose between her two lovers: one is handsome, the other rich:

Jole mere ke frai? / de deus amanz su mis en plai

Li uns est beaus cu[m] fleur de maii / li autre est riches ben le sei

Or quei ke me seit a fere / pite del douce meyre

Dear mother what should I do? / I am torn between two lovers

The one is as beautiful as the mayflower / The other is rich as I well know

So what should I do? / Have pity on me, sweet mother.

The mother replies:

Fille fetes cu[m] les fiz / kant ieo esteie jeovenette jadis

Volu[n]ters a douns me pris / jeu sanz pru nest ben asis

Daughter, do as girls did / back when I was young.

I soon learned / that a game without a prize is not a good bet

She goes on to say that those who let their emotions rule will repent later. The daughter protests that her handsome lover’s kisses are so delightful and that ill-gotten spoils soon turn sour:

Meuz vaut joie orphanine / ke rischesce a marrement

Ky mel leche d’espine / cher l’achate et poi en prent.

Better to be happy in poverty / than to have wealth but a dreary life

He who licks honey from a thorn / pays dearly and gets little in return.

Of course the mother has the final say – she gets her two verses worth, first delivering a stern lesson on the ways of the world:

Le secle est or de tel manere / les riches avaunt les poveres arere

Poi engard hom en la chere / si le riche atorn n’i siet

Marchant a voide almonere / fet a feire poi de espleit.

Such is the way of the world that the rich are in front and the poor behind

And nobody pays any attention to a man’s beautiful face

If he does not have stylish attire and a full purse.

But then she tempers this with wisdom. In the end, it is goodness and honour that count.

Aver est en aventure / Mut est fous ke trop l’aseure

Mes honur et bunte dure / Coment ke del aver alt:

Ke seit entendre mesure / Cil est riche ke moult vault.

Material possessions are transient / only a very foolish person trusts in them too much

But honour and goodness last / whatever happens to possessions.

He who knows moderation / he is rich, for this is valuable.

And if all ends well, the outcome will be a wedding - to the right man!

Miniature of a marriage, Italy (Bologna), last quarter of the 13th century or 1st quarter of the 14th century, Add MS 24678, f. 22r

- Chantry Westwell