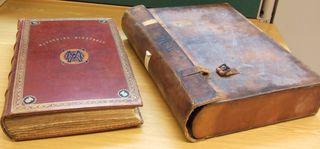

When I first started working at the British Library, I was intrigued to see, on the shelves in the music library, three huge leather cases, each containing a large lavishly-bound album from the 19th century.

Inside the albums are faded photographs of aristocratic-looking men and women, many with musical instruments. There are also concert programmes, drawings and watercolours, and hundreds of newspaper cuttings, all carefully pasted in. With the three large volumes are some notebooks, a manuscript score and a small glass case of badges.

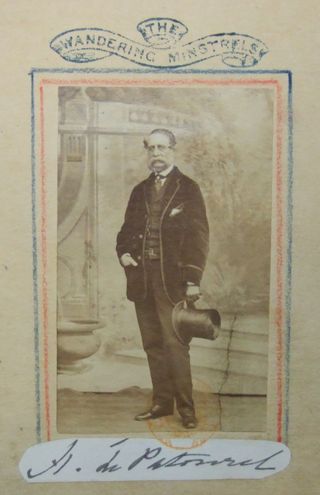

This is the archive of a long-forgotten Victorian orchestra, the Wandering Minstrels. Following its acquisition in the early 20th century, the archive was simply catalogued as “Records of "The Wandering Minstrels," a Musical Society which gave Charity Concerts in various places 1860-1898.” I did a little more research, and it quickly became clear that in their own day the Wandering Minstrels had known extraordinary fame. But modern accounts of musical life in Victorian Britain make only fleeting references to them: the Wandering Minstrels have faded, like their photographs, from history.

The Wandering Minstrels and their archive will shortly see the light of day once more, however, as they are the subject of the Music Feature on BBC Radio 3 tomorrow, Saturday 18 August, 12.15-13.00. In the programme Sarah Walker investigates the history of the orchestra, visiting the British Library to look at their archive, and travelling to some of the places the orchestra performed.

You can hear me talking to Sarah about the Wandering Minstrels and their archive in the programme. I have also just completed a detailed catalogue of the archive, which you can see in the British Library’s Archives and Manuscripts Catalogue.

The Wandering Minstrels were an amateur orchestra of forty or so players, drawn from the ranks of the aristocracy and military. The Earl of Wilton and his sons were leading lights in the orchestra and, for many years, the Earl’s younger son, the Honourable Seymour Egerton, was conductor and president.

The Wandering Minstrels conscientiously documented their activities. Their albums of posters, photographs and concert programmes shine a light on a little-studied aspect of musical life in the 19th century: concerts given by noble amateurs. The albums provide information on the music performed, the structure of the concerts and Victorian programming habits, and show which composers - and which musical works - were popular. (Mendelssohn and Gounod were the most popular composers, by a long way.)

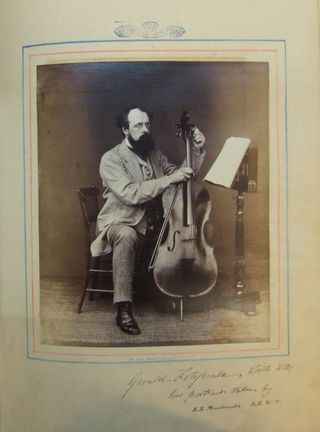

Among the Wandering Minstrels and their circle were several individuals interested in that relatively new medium, photography. The archive is full of photographs of members of the society, their friends and families, and, perhaps of greater interest to the historian, photographs of buildings and streets in the towns and cities they visited.

Among their social circle were several talented artists, who designed programmes for the orchestra, sketched the players, and occasionally members of their audiences, and who presented them with drawings and paintings for their archive. There are also some poems and humorous notes.

The Wandering Minstrels were assiduous collectors of reports of their concerts, and these too were pasted into the albums. It is interesting to see that they kept the bad reviews as well as the good ones! The reviews include many revealing eyewitness reports of the occasions, the venues, and the attitudes and appearance of the audiences. As well as material relating to their own activities, the Minstrels collected old prints and drawings, which were also pasted into the albums.

The albums also contain information on the finances of the organisation. They reveal that in their heyday the Wandering Minstrels filled the best concert halls in London. They toured England giving several hundred concerts over their nearly 40 year history, mainly but not exclusively for charity. By the time they disbanded in 1898, they had raised over £16,000 for good causes - a huge sum in those days. They also popularized the 'smoking concert' - an exclusive social gathering at which gentlemen (and occasionally ladies) would gather to drink, dine, and listen to high-quality music and - the gentlemen only - to smoke. The Wandering Minstrels also gave the very first concert at the Royal Albert Hall in 1871 - a concert for the workmen who had just finished building the hall!

The orchestra named themselves 'the Wandering Minstrels' because of their habit of travelling around the country to give their concerts. The name was probably a slightly tongue-in-cheek one: the so-called wandering minstrels of earlier times had been musicians at the bottom end of the social scale. They travelled from town to town, scraping a living from their playing. The Victorian Wandering Minstrels were right at the other end of the social spectrum, and didn't need to earn a living from music. They performed for their own enjoyment and for philanthropic purposes.

It's very tempting to think that Gilbert and Sullivan's song 'A wandering minstrel I' from The Mikado was written with a nod and a wink towards the Victorian Wandering Minstrels orchestra. Like them, the Wandering Minstrel in The Mikado, Nanki-Poo, was an aristocrat, in his case the son of the Mikado of Japan in disguise as a humble musician. Sullivan was friendly with the conductor of the Wandering Minstrels, and even performed with them on occasion. The Wandering Minstrels were at the height of their fame when The Mikado was premiered in 1885, and it seems likely that the audience would have recognised a topical reference in 'A wandering minstrel I'.