Traditional

Thai medicine is a holistic discipline involving extensive use of indigenous

herbal and massage/pressure treatment combined with aspects of spirituality and

mental wellbeing. Having been influenced by Indian and Chinese concepts of

healing, traditional Thai medicine understands disease not as a physical matter

alone, but also as an imbalance of the patient with his social and spiritual

world.

Thai medical

manuscripts written during the 19th century give a broad overview of

different methods of treatment and prevention, of the understanding and

knowledge of the human body, mind/spirit and diseases. In

1831, King Rama III ordered the compilation of various medical treatises to be

used as teaching materials for the newly established royal medical schools at

Wat Phrachetuphon (Wat Pho) and Wat Ratcha-orot in Bangkok. Wat Phrachetuphon

formally became the first Royal School of Medicine in 1889 and still runs a Thai Traditional

Medical School today.

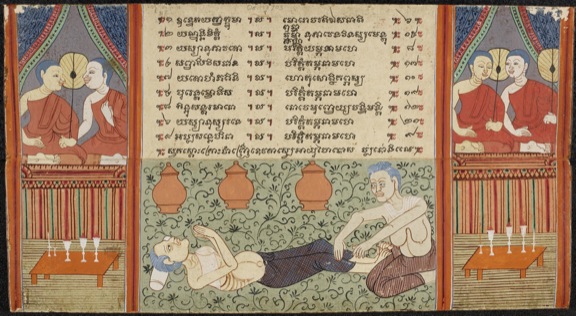

This folding book, containing extracts from

the Vinaya Pitaka and the legend of Phra Malai (a monk who is believed to have travelled to heavens and hells

through the powers of meditation), depicts two elderly women, one

massaging the legs of the other woman lying down on the floor with her hands

folded in prayer. In the background earthenware vessels contain traditional

medicines, which were usually boiled in big pots and then taken throughout the

day (Or 13703, f. 81).

This folding book, containing extracts from

the Vinaya Pitaka and the legend of Phra Malai (a monk who is believed to have travelled to heavens and hells

through the powers of meditation), depicts two elderly women, one

massaging the legs of the other woman lying down on the floor with her hands

folded in prayer. In the background earthenware vessels contain traditional

medicines, which were usually boiled in big pots and then taken throughout the

day (Or 13703, f. 81).

Medical

manuals and handbooks (khamphi phaetsāt songkhro) describe the anatomy

and physiology of the human body, diseases and their possible causes, and methods

of diagnosis and treatment. Some of these books are finely illustrated with

human figures and diagrams; sometimes the human figures themselves appear like

diagrams, particularly in massage treatises (tamrā nūat). Other manuals

contain knowledge in the field of midwifery and herbalist practices including

recipes for the preparation and use of herbal medicines (tamrā yā samunphrai).

Most of these manuals were based on the knowledge and texts used by the royal

physicians at the Thai court. Thai traditional medicine can be traced back to

the Dvaravati (6th-13th centuries) and Sukhothai

(ca.1238-1438) kingdoms according to stone inscriptions and pharmaceutical

artefacts. Under King Narai (1656-1688), the first Thai pharmacopeia known as ‘Tamra Phra Osot Phra Narai’ was compiled

by royal physicians.

According

to the medical treatises, the human body consists of 42 elements, belonging

to four groups (earth, wind, water and fire). If one or several of these

elements are in disorder, it causes disease. The traditional Thai physician

would have to find out which elements were unbalanced and why, and then try to

restore the balance between them. This could be achieved by various methods,

which included treatment with herbal and other supporting natural remedies,

pressure points massage and body or head massage, as well as physical exercise

(Yoga), meditation and dieting – or a combination of several of these methods.

A

massage manual from Bangkok (Or 13922)

Or 13922, ff.

1-5

This

lavishly illustrated paper folding book (samut khoi) with black

lacquered covers is a manual for pressure massage in Thai language and script. It

describes the channels in the body terminating in pressure points and how

pressure massage can be used to treat certain illnesses. It is believed that

the book was produced at Wat Phrachetuphon, Bangkok, in the first half of

the 19th century as the text clearly relates to the medical

inscriptions from that time on the walls of this royal temple, which is

adjacent to the royal palace.

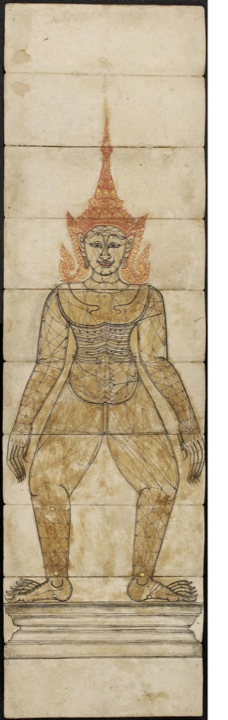

It begins with an unlabelled large gilded diagram of the human body (Or 13922, ff.

1-5, shown on the left). It gives an introductory overview of the network of

channels within the body. The figure is shown wearing lavish gilt royal

headgear and the main pressure points are also gilt, whereas the rest of the

body has been drawn in black ink. The area around the navel is a central point

where many channels start.

This manuscript can be viewed in full on our digitised

manuscripts webpage.

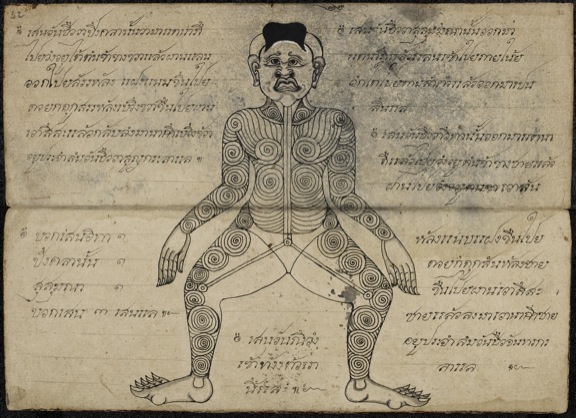

The diagram below (Or 13922, f. 32) indicates the channels and main pressure areas of the body,

stylistically represented by spiralling calligraphic lines. One channel known

as pinkhalā, for instance, begins at the navel and proceeds past the

base of the right leg to exit via the back. Another channel, the susumannā

line proceeds from the navel into the chest, climbs through the body and exits

through the tongue.

Or 13922, f. 32

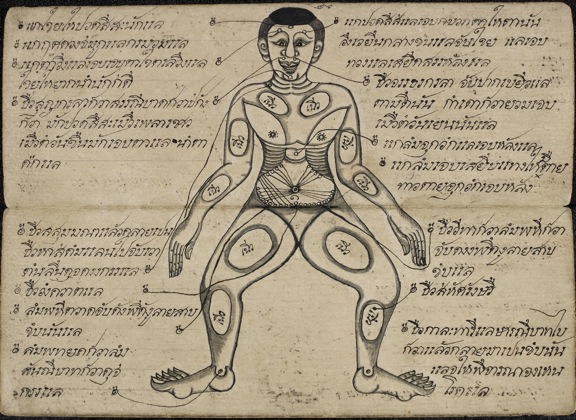

In most

of the diagrams, the pressure points are named and their functions are

described in detail. The fleshy areas of the body are all neatly labelled as

such, so that the book also gives insight into the Thai understanding of the

human anatomy. Each illustration indicates the points of the body that can be

treated with pressure massage, which diseases can be treated and how many times

certain points have to be massaged.

Here the pressure point above the right eye is identified as the one for

treating pains and infections of the eye as well as dizziness. In the middle of

the forehead is a point for treating headaches, fevers and congestion of mucus

and haemorrhage in the nasal passage. (Or 13922, f. 36)

Here the pressure point above the right eye is identified as the one for

treating pains and infections of the eye as well as dizziness. In the middle of

the forehead is a point for treating headaches, fevers and congestion of mucus

and haemorrhage in the nasal passage. (Or 13922, f. 36)

Massage in traditional Thai society

Not only massage treatises, but also

illustrated Buddhist manuscripts and literary texts provide evidence that massage

treatments were very popular and frequently used at all levels of Thai society. Buddhist manuscripts, such as the first example above, often contain genre scenes from the everyday

life of Buddhist monks and lay people.

Lively descriptions of situations where

pressure massage was carried out can be found in one of the most notable Thai

literary works, Khun Chang Khun Phaen, a lengthy narrative of love and

death which began in a folk tradition of oral performance (sēphā), but

was adopted by the royal court and transformed into written text in the early

19th century. Quite often, it seems, pressure massage was the method

of first choice in emergencies such as this (Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit (eds.),

The tale of Khun Chang Khun Phaen. Siam’s great folk epic of love and war. Chiang Mai, 2010, p. 236):

Her body

was motionless. ‘Wanthong, oh Wanthong!’ No sound came in return. With body

trembling, she shouted, ‘Servants! Come to help, quick!’ The servants all came

up in a rush. They propped Wanthong up. They wept. They massaged both her legs.

They pressed between her eyebrows to open her eyes. Siprajan cried out,

‘Softly, now! Why don’t you massage her jaw?’ She sat with a kaffir lime in her

hand, staring vacantly. ‘Do everything you can, everything.’ Someone bit

Wanthong’s big toe, and then she murmured.

Jana Igunma, Asia and African Studies

Follow us on Twitter @BLAsia_Africa

John Falconer

Mughals exhibition, Queen's Palace, Babur's Gardens, Kabul

John Falconer

John Falconer

John Falconer