Posted on behalf of Bob Nicholson.

The Victorian Meme Machine is a collaboration between the British Library Labs and Dr Bob Nicholson (Edge Hill University). The project will create an extensive database of Victorian jokes and then experiment with ways to recirculate them out over social media. For an introduction to the project, take a look at this blog post or this video presentation.

Stage One: Finding Jokes

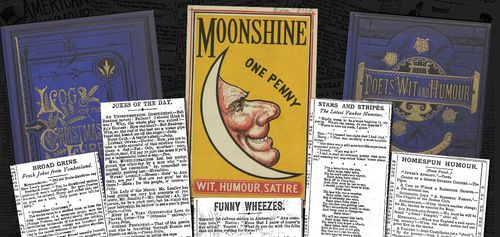

Whenever I tell people that I’m working with the British Library to develop an archive of nineteenth-century jokes, they often look a bit confused. “I didn’t think the Victorians had a sense of humour”, somebody told me recently. This is a common misconception. We’re all used to thinking of the Victorians as dour and humourless; as a people who were, famously, ‘not amused’. But this couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact, jokes circulated at all levels of Victorian culture. While most of them have now been lost to history, a significant number have survived in the pages of books, periodicals, newspapers, playbills, adverts, diaries, songbooks, and other pieces of printed ephemera. There are probably millions of Victorian jokes sitting in libraries and archives just waiting to be rediscovered – the challenge lies in finding them.

In truth, we don’t know how many Victorian gags have been preserved in the British Library’s digital collections. Type the word ‘jokes’ into the British Newspaper Archive or the JISC Historical Texts collection and you’ll find a handful of them fairly quickly. But this is just the tip of the iceberg. There are many more jests hidden deeper in these archives. Unfortunately, they aren’t easy to uncover. Some appear under peculiar titles, others are scattered around as unmarked column fillers, and many have aged so poorly that they no longer look like jokes at all. Figuring out an effective way to find and isolate these scattered fragments of Victorian humour is one of the main aims of our project. Here’s how we’re approaching it.

Firstly, we’ve decided to focus our attention on two main sources: books and newspapers. While it’s certainly possible to find jokes elsewhere, these sources provide the largest concentrations of material. A dedicated joke book, such as this Book of Humour, Wit and Wisdom, contains hundreds of viable jokes in a single package. Similarly, many Victorian newspapers carried weekly joke columns containing around 30 gags at a time – over the course of a year, a regularly printed column yields more than 1,500 jests. If we can develop an efficient way to extract jokes from these texts then we’ll have a good chance of meeting our target of 1 million gags.

Our initial searches have focused on two digital collections:

1) The 19th Century British Library Newspapers Database.

2) A collection of nineteenth-century books digitised by Microsoft.

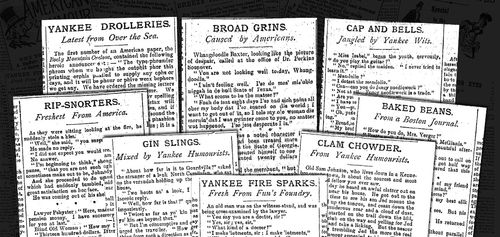

In order to interrogate these databases we’ve compiled a continually-expanding list of search terms. Obvious keywords like ‘jokes’ and ‘jests’ have proven to be effective, but we’ve also found material using words like ‘quips’, ‘cranks’, ‘wit’, ‘fun’, ‘jingles’, ‘humour’, ‘laugh’, ‘comic’, ‘snaps’, and ‘siftings’. However, while these general search terms are useful, they don’t catch everything. Consider these peculiarly-named columns from the Hampshire Telegraph:

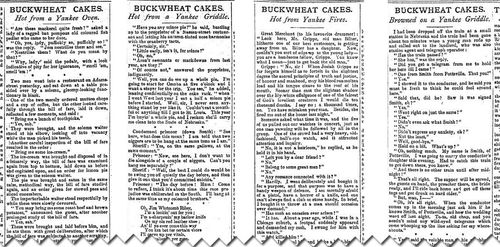

At first glance, they look like recipes for buckwheat cakes – in fact, they’re columns of imported American jokes named after what was evidently considered to be a characteristically Yankee delicacy. I would never have found these columns using conventional keyword searches. Uncovering material like this is much more laborious, and requires us to manually look for peculiarly-named books and joke columns.

In the case of newspapers, this requires a bit of educated guesswork. Most joke columns appeared in popular weekly papers, or in the weekend editions of mass-market dailies. So, weighty, morning broadsheets like the London Times are unlikely to yield many gags. Similarly, while the placement of jokes columns varied from paper to paper (and sometimes from issue to issue), they were typically placed at the back of the paper alongside children’s columns, fashion advice, recipes, and other miscellaneous tit-bits of entertainment. Finally, once a newspaper has been proven to contain one set of joke columns, the likelihood is that more will be found under other names. For example, initial keyword searches seem to suggest that the Newcastle Weekly Courant discontinued its long-running ‘American Humour’ column in 1888. In fact, the column was simply renamed ‘Yankee Snacks’ and continued to appear under this title for another 8 years.

Tracking a single change of identity like this is fairly straightforward; once the new title has been identified we simply need to add it to our list of search terms. Unfortunately, the editorial whims of some newspapers are harder to follow. For example, the Hampshire Telegraph often scattered multiple joke columns throughout a single issue. To make things even more complicated, they tended to rename and reposition these columns every couple of weeks. Here’s a sample of the paper’s American humour columns, all drawn from the first 6 months of 1892:

For papers like this, the only option is to manually locate jokes columns one at a time. In other words, while our initial set of core keywords should enable us to find and extract thousands of joke columns fairly quickly, more nuanced (and more laborious) methods will be required in order to get the rest.

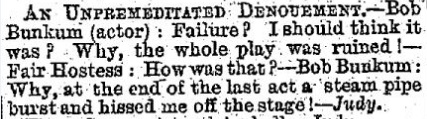

It’s important to stress that jokes were not always printed in organised collections. Some newspapers mixed humour with other pieces of entertaining miscellany under titles such as ‘Varieties’ or ‘Our Carpet Bag’. The same is true of books, which often combined jokes with short stories, comic songs, and material for parlour games. While it’s fairly easy to find these collections, recognising and filtering out the jokes is more problematic. As our project develops, we’d like to experiment with some kind of joke-detection tool that pick out content with similar formatting and linguistic characteristics to the jokes we’ve already found. For example, conversational jokes usually have capitalised names (or pronouns) followed by a colon and, in some cases, include a descriptive phrase enclosed in brackets. So, if a text includes strings of characters like “Jack (…):” or “She (…):“ then there’s a good chance that it might be a joke. Similarly, many jokes begin with a capitalised title followed by a full-stop and a hyphen, and end with an italicised attribution. Here’s a characteristic example of all three trends in action:

Unfortunately, conventional search interfaces aren’t designed to recognise nuances in punctuation, so we’ll need to build something ourselves. For now, we’ve chosen to focus our efforts on harvesting the low-hanging fruit found in clearly defined collections of jokes.

The project is still in the pilot stage, but we’ve already identified the locations of more than 100,000 jokes. This is more than enough for our current purposes, but I hope we’ll be able to push onwards towards a million as the project expands. The most effective way to do this may well to be harness the power of crowdsourcing and invite users of the database to help us uncover new sources. It’s clear from our initial efforts that a fully-automated approach won’t be effective. Finding and extracting large quantities of jokes – or, indeed, any specific type of content – from among the millions of pages of books and newspapers held in the library’s collection requires a combination of computer-based searching and human intervention. If we can bring more people on board we’ll be able to find and process the jokes much faster.

Finding gags is just the first step. In the next blog post I’ll explain how we’re extracting joke columns from the library’s digital collections, importing them into our own database, and transcribing their contents. Stay tuned!