Ian Cooke, co-curator of Propaganda: Power and Persuasion provides a round-up of propaganda inspired blogs from other British Library bloggers.

One of the unexpected pleasures of curating an exhibition at

the Library was receiving a limerick from our chief limericist (that’s a word,

isn’t it?) Hedley Sutton. It goes like this:

A curator whose surname was Cooke

Said "I hope you will all have a look

At our new exhibition:

I've made it my mission

To cover each cranny and nook."

But of course it wasn’t a mission that I completed alone.

Jude England, Head of Social Sciences and co-curator of Propaganda: Power and

Persuasion, and I relied on the experience and knowledge of a very large number

of people here at the British Library. The exhibition covers many countries and

languages, and a lot of different formats such as bank-notes, postage stamps,

film, sound, posters, leaflets etc. There’s no way we could have done this by

ourselves, and the creativity and enthusiasm of our colleagues here in

responding to the exhibition was one of the nicest things about putting the

exhibition together.

In the exhibition, you’ll see the question, “what’s the most

thought-provoking piece of propaganda that you have seen?” Answers to

#blpropaganda please, and many thanks to the person who answered, ’50 shades of

grey’.

I’ve written about the

item in the exhibition that had the biggest impact on me. Others have

written about items in the exhibition on our other British Library blog pages,

and I wanted to bring them together here.

James Montgomery Flagg (artist), I want you for U.S. army. c.1917. Loan courtesy of Anthony d’Offay, London.

Starting off with the most prominent image from our

exhibition, Uncle Sam has been hard to miss if you’ve visited the Library

recently (or just walked past the Euston Road). Over on our Americas studies blog,

Carole

Holden has written about the origins of this iconic poster, and its artist,

James Montgomery Flagg. It’s also served as a dramatic backdrop for

photographs, such

as this one of Justin Webb.

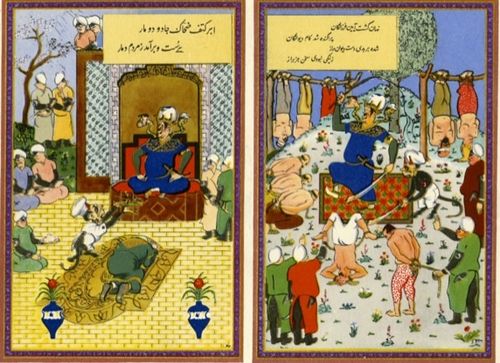

British World War Two propaganda for use in Iran, drawing on a well-known Persian epic, the Shahnameh (COI Archive PP/13/9L)

The two themes that have been most prominent are the use of

propaganda to create a sense of common identity, and, conversely, the use of

propaganda to define an enemy and demonise others. John O’Brien describes British

plans to discredit the Quit India movement during World War Two. Another

example of British wartime propaganda attempted to use the Persian epic, the

Shahnameh, or ‘Book of Kings’ to present Hitler as a demonic tyrant, defeated

by the heroic warriors Churchill, Stalin and Roosevelt. Nur

Sobers-Khan explains the history and images used in these propaganda postcards

aimed at an Iranian audience.

Germany was also active in its use of propaganda aimed at

states in the Middle East. The tactics used were similar, this time portraying

Britain as the oppressor and Germany on the side of liberation in the region.

Radio broadcasts in Arabic language were used to promote German victories and

encourage dissent against Britain. Writing on our Untold Lives blog,

Louis Allday uncovers evidence of British

reaction to the broadcast of German radio propaganda in Sharjah, on the

Persian Gulf.

One of the most successful examples of propaganda that you’ll

see in the exhibition is the ‘Four Freedoms’ series of posters by Norman

Rockwell. These posters have great emotional power, using domestic and local

scenes to illustrate the rather abstract theme of ‘freedom’. Carole

Holden writes about the development and history of these posters, which are

credited with raising over $130 million dollars in war bonds.

Bert, the Turtle:

‘The Duck and Cover Song’ Leon Carr, Leo Corday & Leo Langlois. 1953 ©

Sheldon Music Inc

Propaganda remained an important tool during the cold war,

and one of our stranger finds dates from this period. Katya

Rogatchevskaia describes anti-Soviet propaganda produced by a Russian

organisation active in West Germany. This includes two template images for

printing propaganda images (complete with instructions on how to make your

printing ink). In the United States, Bert the Turtle was used to instruct

children on how to respond to a nuclear attack. This seemingly-simple figure

has proved to be one of the most complex examples of propaganda – with some

people disputing its description as propaganda. The

story of ‘Duck and Cover’, and some of the subsequent analysis of this

campaign, is recounted by Carole Holden on the Americas studies blog.

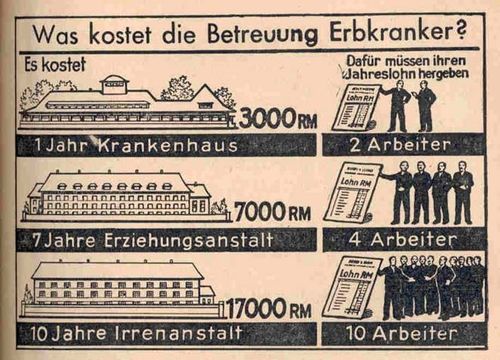

'Was Kostet die

Betreuung Erbkranker', from Rechenbuch für Volksschulen. Gaue Westfalen-Nord

u. Süd. Ausgabe B. Heft V – 7. und 8. Schuljahr. (Leipzig, [1941]). British

Library YA.1998.a.8646

In our exhibition you’ll see further examples of propaganda

designed for children, the most disturbing of these being a maths textbook

produced for use in schools in Nazi Germany. One question in the book asks how

much it costs (in terms of a worker’s salary) to care for the ‘hereditarily unfit’.

In ‘Propaganda

in the schoolroom’, Susan Reed explains more about this textbook and other

examples within the Library’s collections.

Revisiting these blog posts reminds me of the breadth of

interests and activities across the Library, and I’m looking forward to seeing

more as the exhibition continues. If this has inspired you to create your own

propaganda, don’t forget our competition for new designers, in collaboration

with Artsthread. Fran

Taylor explains more on our Inspired by … blog. The brief is to come up

with a new design, illustration or short film to encourage people to change

attitudes and behaviour on health. You can get food for thought, or at the very

least a recipe for bhajiyas, from John

O’Brien’s description of booklets from the Government of India’s nutrition

campaign in 1945.