Last week we featured part 1 of a Q&A with writer, artist and composer Rob St John about his collaborative art / science project Surface Tension, an audiovisual work that explores pollution issues facing the River Lea. In the final part of this conversation, Rob talks about transforming field recordings and scientific data into a musical composition.

Once the fieldwork had been completed, you returned to the studio and began to work on the final composition. In the accompanying book you say that you “processed the recordings and photographs using methods designed to echo the pollution of the Lea to create the music and images in this book”. What methods did you use?

One of the wider ongoing themes (and questions) in my work is how to incorporate environmental issues and ecological processes into creative production. I’m especially interested in how narratives about landscape and environment might be (re)made through the influence of creative work, particularly in a time that environmentalists are slowly coming to term the Anthropocene, which broadly describes a world in which humans have influenced every patch of the ‘natural’ world, however subtly. And a central part to this is the issue of uncertainty, hybridity and flux in the environment: terms like ‘nature’ and ‘wilderness’ lose their certainty.

I’m not saying I have an answer to any of this, but I think that by explicitly incorporating uncertainty and chance ecological processes into your creative work, you can respond to the various blurrings and hybridisations of natural/cultural, wild/managed, native/invasive descriptions and categorisations in the environment, and in doing so foster new, and hopefully fertile conversations and ideas amongst people who come across the work.

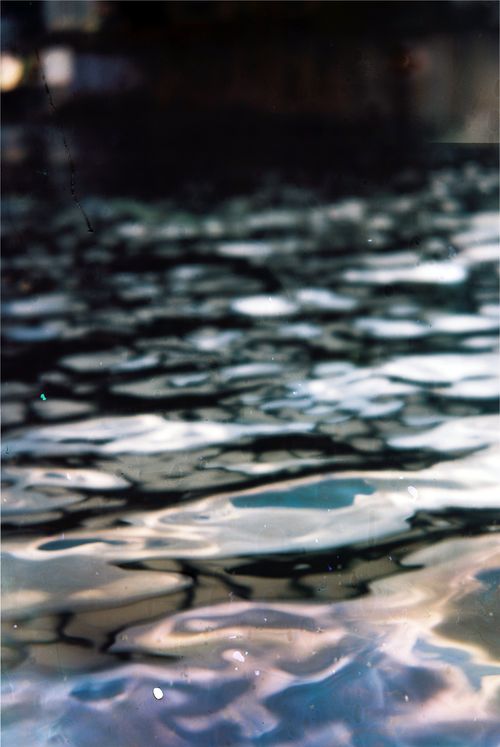

In Surface Tension, I was interested in the polluting and degrading properties of the river’s water. A key ecological narrative from organisations like Thames21 describes how the river is amongst the most polluted in the country, with regular fish kills due to high pollution and low dissolved oxygen levels. And this is pretty obvious to the naked eye when walking the river in the summer: there are blankets of luminous green weed, and hydra-head swirls of oil all over the surface of the middle and lower river, and litter washed up in every backwater. Yet, despite all of this, shoals of fish and flocks of water birds and insects still survive in the river (again, it’s that remarkable thing of species and ecosystems still somehow finding a way to keep ticking over, even in the most human altered landscapes). Sadly, it’s only when there is a large fish kill (as happens most summers) that the diversity of the river is actually revealed (and of course, reduced again).

So, this has been quite a lot of throat clearing as a means of getting round to telling you about how I used water baths of Lea water to ‘process’ analogue tape and films in the project. Field recordings and new compositions for the project were overlain onto 1/8 inch tape, and then the tapes were spliced into short loops, usually about 10 seconds long. The tape loops were then soaked in the baths of river water – duckweed, oil slicks, water snails and doubtless numerous dissolved chemicals – for a month, shimmering like elvers amongst the murk. The tapes were then taken out, cleaned, dried and replayed. Inspired by the American artist William Basinkski’s Disintegration Loops, I recorded this replaying process, as over time the tapes began to disintegrate and fall apart whilst still spinning.

Degraded Piano Loop

The water bath had etched various tributaries and knickpoints into the magnetic layer of the tapes, meaning each recording disintegrated in a pattern partially determined by the action of the river: another form of water and chemical erosion. Elements of the recordings were slowly lost, creating subtle new melodies, rests and rhythms. The film negatives were processed in the same way and rescanned. Here, another process of reshaping the images occurred, as they each developed new marks, light flares and imperfections from the river and its inhabitants.

How did you incorporate scientific data into the work?

As with the tape loops, I wanted to let elements of the river and ecology guide the production of the final sound and vision in the project. So alongside this more tactile, physical processing, I used the Ableton Live and Max MSP software to sonify pollution data sets taken by Thames21 and University College London at seven points along the river. Sonification is the process of translating data into sound, much as you might create a visualisation like a graph or map. There’s plenty of interest in sonification at the moment, partly as a creative way of communicating or remaking scientific research, and partly as a means of asking ‘are there certain patterns and trends in a data set that might be easier to spot through hearing, rather than seeing?’

So, for the sonifications, I mapped various pollution parameters (nitrate, phosphate, bacteria and so on) onto sound production parameters (LFO, hi and lo pass filters and so on) in a Max program called Granulator, which mixes hundreds of tiny micro-second samples of sound together. This seemed an appropriate method by which to make the invisible, dissolved pollutants in the river somehow audible. In doing this work, I very quickly realised that any sonification will inevitably expose a tension between the data set used, and the aesthetic and practical choices made in what sound to sonify and how. Is a simple sine wave the most ‘objective’ sound to allow the dataset to ‘produce’? I decided to use harmonium and piano samples (the harmonium, in part because of the reeds – reed planting is one method that Thames21 use to ‘buffer’ pollutants from entering the river), which were gradually remade into something more ambient and granular by the sonification.

Pollution Data Sonification

And of course, there were aesthetic and practical choices here, too. A shift in the parameters and the granulator would have turned out crackling noise: interesting, sure, but much less ‘listenable’. Was there any noticeable trend in the sound in response to the data? Not really: but these were large, complex and variable datasets. We often hear sonifications of more predictable and smooth environmental data, such as tide oscillations. Aside from producing interesting snippets of sound for the project, the sonifications here were of little analytical use, and I wonder if this is a major thing for people to think about if sonification is to become more expansive and useful as a technique: how to deal with complexity?

A final ‘sonic geography’ technique was to map the reverbs of a number of historical architectural spaces such as the Three Mills complex along the river. By creating an ‘impulse’ (a burst balloon, a starting pistol) in a space, and recording the way the sound decays, a convolution reverb which replicates the acoustic ‘fingerprint’ of that space can be generated. Again, this seemed a neat and appropriate production tool when attempting to play about with ideas of how the Lea Valley landscape has changed (and will do in the future), by blurring various spaces in which water has flown, been mixed, polluted and abstracted in the past: echo chambers for the various traces of the river.

What’s the result of this work?

All these production techniques were used in tandem with a set of new compositions on guitar, cello, piano and analogue synth, recorded partly with Pete Harvey in Scotland. The final piece of music is half an hour of field recordings, music, sonifications and tape loops, all blurring and overlapping, and was released alongside a book of writing and photographs in April, now archived at the British Library. A sound map of many of the recordings, and the locations where they were taken was also made, and some of the photographs have since been exhibited at Stour Space in London and The Lighthouse in Glasgow.

Surface Tension Excerpt

What do you hope people will take away with them when they experience Surface Tension?

I hope they enjoy it! Despite all this theoretical wittering and pondering that’s gone into the work, I wanted to make something that’s really easy and enjoyable to pick up and listen to and read. And then if something sparks your attention, there’s a whole bunch of contextual information that you can spin off into (like this interview, I guess). And maybe to be encouraged to visit the Lea Valley, and to see it in a slightly different light, one that’s neither entirely natural nor urban, planned nor self-willed, but instead a brilliant, unique and odd entanglement of all these things and more.

Rob St John (courtesy Emma Cardwell)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Surface Tension can be consulted in the British Library Reading Rooms (catalogue reference number 1SS0010348)