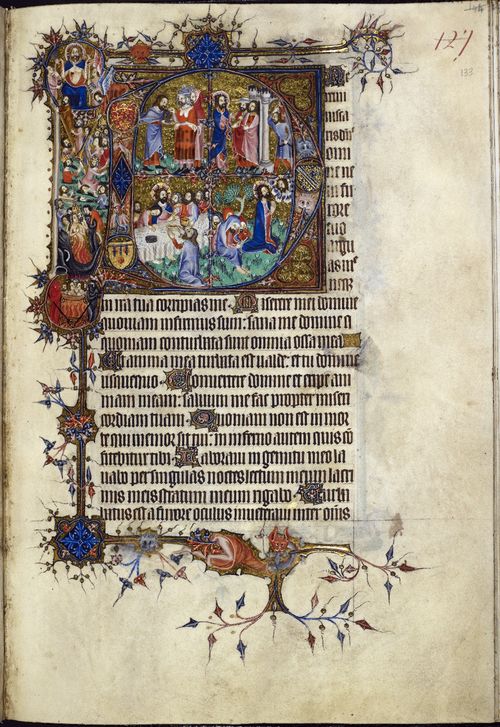

Historated initial 'D'(omini) at the Penitential Psalms: the priests give Judas money (Luke 22:5), Christ sends Peter and John to prepare the passover (Luke 22:8), the Last Supper, the Agony in the Garden, and the Last Judgment in the border, from the Bohun Psalter and Hours, England, second half of the 14th century, Egerton MS 3277, f. 133r.

The Bohun Psalter and Hours (Egerton MS 3277) is, as Lucy Freeman Sandler describes it, 'virtually a royal manuscript'. It was probably produced for Humphrey de Bohun, 7th Earl of Hereford, Essex and Northampton (d. 1373), who was the great-grandson of King Edward I, and the father of Eleanor (who married Thomas of Woodstock, son of Edward III), and of Mary (the wife of Henry of Bolingbroke, who later became Henry IV).

This Psalter is part of a larger group of at least 10 manuscripts that were created for various generations of the Bohun family by a scriptorium and workshop in residence at the main Bohun home of Pleshey Castle, Essex. It is unclear whether this sort of arrangement existed with other noble families of this time, but this may have been a comparatively common practice for the English aristocracy.

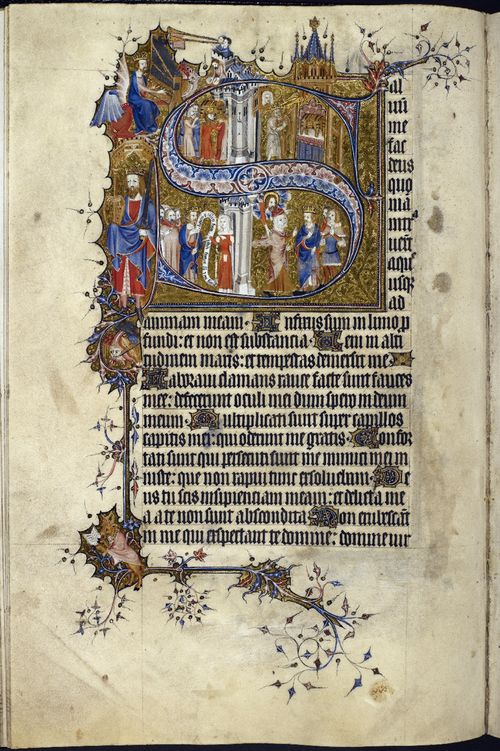

Historiated initial 'S'(alvum) at the beginning of Psalm 68 ('Salvum me fac Deus'), with scenes of the Ark's arrival in Jerusalem, and to the left of the initial, King David standing holding his harp, with a small hybrid musician playing under his feet, from the Bohun Psalter and Hours, England, second half of the 14th century, Egerton MS 3277, f. 46v.

The Bohun Psalter and Hours was probably written around 1361, and the first campaign of illumination – verse initials and line fillers – was likely completed at this time. Little appears to have been done on the manuscript until the 1380s, when work on the Bohun Psalter and Hours was resurrected and the major initials and other miniatures were completed. The original programme of illumination contained nearly 400 subjects, both large and small, although a number of decorated pages were later excised – get in touch if you see anything similar at a car boot sale! As Lucy Freeman Sandler has pointed out, the various 'minor' components of illumination, such as the marginalia, often complement or respond to the 'main' meaning of the historiated initials. For example, see the large historiated initial on f. 29v (which was the opening on display during the Royal exhibition).

Historiated initial 'D'(ixit) of four scenes in the life of David: Saul entering the cave in which David and his men are hiding to relieve himself; David cutting a corner of Saul's robe; David calling after Saul with the corner of his robe and Saul speaking to David, confessing that he believes David will soon be king, at the beginning of Psalm 38, The Canticle of David, from the Bohun Psalter and Hours, England, second half of the 14th century, Egerton MS 3277, f. 29v.

The initial 'D'(ixit) at the beginning of Psalm 38 (above and below) was one of the major divisions of the Psalter, and was commonly marked out for special decoration at this period. The iconography in this scene is remarkable. On the outer edges of the initial are four human and hybrid musicians, playing the viol, horn, cymbals and harp – all instruments mentioned in the Psalter.

Detail of an historiated initial 'D'(ixit) of four scenes in the life of David, at the beginning of Psalm 38, The Canticle of David, from the Bohun Psalter and Hours, England, second half of the 14th century, Egerton MS 3277, f. 29v.

In the centre of the initial are four scenes taken from I Kings: 24 (1 Samuel: 24 in the current division of the Bible). This book narrates the conflict between King Saul and David, and the first scene in the upper left shows Saul and his army searching for David and his men in the wilderness of Engedi. Saul enters a cave in which, unknown to him, David and his men are hiding. Saul is described in various translations of the Bible as needing to 'cover his feet', 'relieve nature', or even 'go to the bathroom', as can be seen in the upper right. David is shown standing behind the vulnerable Saul and, according to the text, his men urge him to kill the king, but instead David cuts off part of Saul’s cloak. After Saul leaves the cave, David approaches him, in the lower scene on the left. David holds out the cut cloth and tells Saul that although he had the opportunity to kill him, he did not, as Saul is his king and the Lord’s anointed. Saul sees this as evidence of David’s righteousness, and proclaims that David will be his successor for the kingdom of Israel; on the lower right David swears fealty – interestingly, with his hand on a book – and Saul anoints him as future king.

Besides depicting this unusual scene from the Bible, this miniature makes a number of ideological points. Bear in mind that this was painted during the Hundred Years' War. If you look on the right, you can see the arms of France in the initial frame, which aligns Saul with the French ruler. On the left part of the initial are the arms of England as well as those of the Bohun family, which are similarly aligned with the ultimately-prevailing King David.

Detail of an historiated initial 'D'(efecit) of the Ark of the Covenant being carried into the Temple, with an ape and a bear in the margins, from the Bohun Psalter and Hours, England, second half of the 14th century, Egerton MS 3277, f. 84r.

On f. 84r (above) is an historiated initial 'D'(efecit in salutare meum anima mea), or 'My soul hath fainted after thy salvation'. This is at Psalm 118:81, a subdivision of what is a very long Psalm indeed. Inside this initial, King Solomon is shown accompanying the Ark of the Covenant, which looks like a chest of pirate booty, into the Temple of Jerusalem (from III Kings 8:6). Similarly, the upright ape standing on the initial is also carrying a bag of money, and seems to mimick the procession below. He is carrying an owl, which would have been understood by medieval readers as a reference to a fairly well-known saying: 'Pay me no less than an ape, an owl, and an ass', although of course the ass is absent.

This ape focuses attention on the piety displayed in the initial, but it may refer to those who laboured to create the manuscript itself, as artists at the time were often described as 'apes of nature'. Further evidence of this can be seen above – look at the bear who sits uncomfortably on the lower extender of the initial, and who appears to be licking a pen, in preparation for working on a scroll of music. This may be intended to represent the scribes who worked on this manuscript.

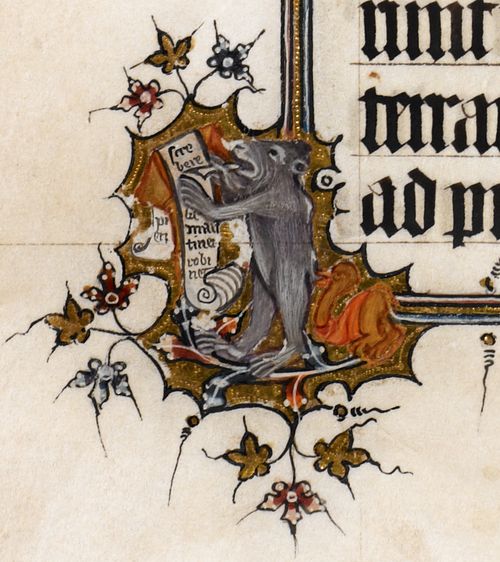

Detail of a marginal illumination of a bear-scribe writing on a scroll, from the Bohun Psalter and Hours, England, second half of the 14th century, Egerton MS 3277, f. 13v.

Lest you think this bear-scribe is too fanciful, see one final detail from f. 13v, the last folio of the first quire. There are a number of bears to be found elsewhere in the Bohun Psalter and Hours, but this one does not seem to be directly related to the text nearby. This bear stands holding a quill and working on a scroll. Behind the bear is a goose, in the act of literally goosing the bear. The first word on this bear's scroll is 'screbere' which is conveniently split so that the second word is bere – of course a reference to the creature itself. But the rest of the text is not so immediately apparent: following 'screbere' is some indecipherable scribbling, and then the names 'mar / tinet' and 'robi / net', and on the back is 'pi / erz'. So these are the names Martin, Robert and Piers – presumably the names of three scribes who worked on this very manuscript.

But what might seem like a self-reference is more complicated, because this image was created not by the scribes but by an artist whose name does not survive. Perhaps he was poking fun at those with whom he worked closely to produce such a well-integrated manuscript? Perhaps this is a partial explanation for the disrespectful goose? A larger question is for whom this sort of humour was intended. Lucy Sandler has noted that the artist responsible for much of this Psalter continued working for the Bohun family for decades after the manuscript was finished, so it is hard to imagine that they objected to this in-joke. An inventory made of the library at Pleshey Castle at the end of the 14th century includes more than 120 books, including a number of Bibles and other religious texts. Indeed, it is likely, knowing what we do of the Bohuns, that they would have appreciated this clever interplay between human and animal, text and image.

- Sarah J Biggs