When a friend recently commented that he thought it strange and amusing to see foreign house names in a traditional-looking Yorkshire village, he was assuming that such names were given in pretention, or in sentimental memory of a holiday abroad. It seems natural to think of cities attracting migrants and refugees, but not of villages as distinctly conservative, even insular, in their Olde Worlde Englishness.

In reality, of course, the picture is more complicated. On the very outskirts of Leeds, not far from where I live, is one grey stone village whose origins are every bit as cosmopolitan as an inner-city area. Its name is Fulneck, and it shares its name with a settlement in the eastern part of the Czech Republic: Fulnek, Moravian Silesia. The Yorkshire village was established in 1743 by refugees from the Counter-Reformation in Bohemia and other Habsburg lands. They were members of the Moravian Church, one of the earliest Protestant Churches of all and the oldest Protestant denomination in the Czech lands, which had its roots in the Hussite movement of the 15th century.

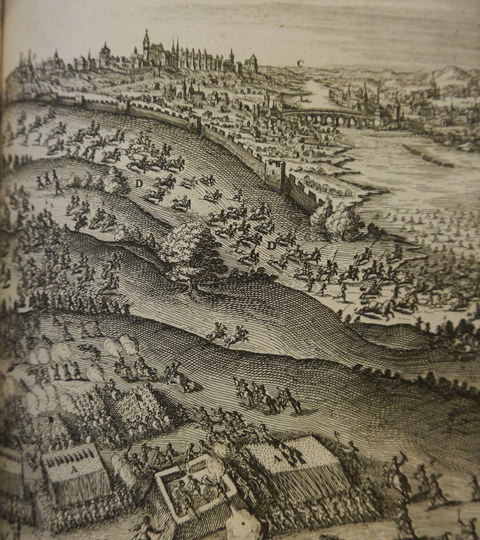

By 1600, a majority of the inhabitants of the provinces of Moravia and Bohemia (the present-day Czech Republic) were under the influence of Hussite churches or schools, and might be said to have become Protestant. The churches established printing presses, and held services in Czech and German in preference to Latin. For a long time, the imperial court tolerated this, and was even sympathetic, but the arrival of the Jesuits and election of the vengefully Catholic Ferdinand II as King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor changed things. The events that followed are some of the most evocative in Czech history. The Second Defenestration of Prague, when representatives of the Protestant estates threw the Emperor’s envoys from the window of the Bohemian Chancellery, sparked the Thirty Years War. Its first battle was the disastrous White Mountain, which wiped out the Protestant nobility and would become a powerful symbol of the Habsburgs’ destruction of the nation and suppression of the Czech language. In creating a national mythos for the Czechoslovak state, Tomas Masaryk would constantly refer back to this period of history.

The Battle of White Mountain, November 1620, detail from an illustration by Matthäus Merian in Johann Philipp Abelin, Theatrum Europaeum (Frankfurt am Main, 1643) British Library 800.m.3-5.

The Battle of White Mountain, November 1620, detail from an illustration by Matthäus Merian in Johann Philipp Abelin, Theatrum Europaeum (Frankfurt am Main, 1643) British Library 800.m.3-5.

The survivors of White Mountain went into hiding in caves and crevices around the borders. Some of these hiding places are marked today, often as detours from the innumerable well-marked hiking routes that criss-cross the country. The Moravian Brethren – originally of Bohemian origin – took their name from the fact that they continued to live in hiding in Moravia worshipping illegally for almost a century. Many other groups went abroad, firstly to other states in the Holy Roman Empire where the Counter-Reformation was less entrenched, and then later overseas, to Britain, France, the Netherlands or North America. In due course, the Moravians followed, moving first to Herrnhut in Saxony, where they were protected by Nikolaus von Zinzendorf, and then to England. This is the origin of the Fulneck Moravian Settlement.

The Fulneck Settlement originally consisted of separate houses for men and women, both of which are still standing on either side of the Moravian Chapel, as well as some married accommodation. Possibly the most famous of the children born in eighteenth-century Fulneck was Henry Benjamin Latrobe, architect of the Capitol building in Washington DC. His father was a Moravian minister.

The old Moravian Chapel in Fulneck. (Photograph J.Ashton/C.Martyn)

Benjamin Latrobe was educated in Upper Lusatia, Saxony, from where his community had emigrated, but Fulneck itself has a school, established in 1753, which went on to become a mainstream independent school. Its pupils have included the future Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith (born in Morley, which is now also part of Leeds) and Dame Diana Rigg. Asquith hated his time there and refused to come back as a famous old boy to give prizes, a fact not everyone with an interest in Fulneck is eager to advertise!

Fulneck school, overlooking the valley (Photograph J.Ashton/C.Martyn)

Modern Fulneck still consists of just one street, built on a ridge above a green valley. Many of the people living there are Moravians still, and they run a small museum of their history in England and Europe. The volunteer staff are very knowledgeable, and truly bring the eclectic little collection to life. Links to Herrnhut and other Moravian communities are also maintained.

The Museum in Fulneck; the building is typical of those in the village. (Photograph J.Ashton/C.Martyn)

Among the British Library’s collections are various locally-produced histories of the Settlement, as well as a copy of The Brotherly Agreement and Declaration concerning the Rules and Orders of the Brethren's Congregation at Fulneck, published in 1777 (4661.b.4.), and a cantata composed by Edward Sewell to celebrate its centenary (Cantata, composed in commemoration of the Fulneck Centenary Jubilee, April 19th 1855. London, 1855; R.M.14.e.27.). Small but persistent, this little community of exiles used its own corner of a foreign field to maintain the Reformation ideals on which Masaryk would found the Czechoslovak state.

Janet Ashton, WEL Cataloguing Team Manager