The artistic career of Colonel Robert Smith (1787-1873), of the Bengal Engineers, is one of the most interesting among the many soldier artists who were in India in the 18th and 19th centuries. Although his work is well known, there are certain confusions about his output which this note is designed to clarify. There were in fact two soldier artists Robert Smiths in India in the early 19th century. Our Smith was in India from 1805 to 1830, in the Bengal Engineers. Eight of his watercolours (WD2087-94) and five sketchbooks packed with topographical drawings (WD309-13) are in the British Library’s collections, as well as two small oil paintings (F864-5, see: http://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/yourpaintings/artists/smith-colonel-robert-17871873). The sketchbooks all date from 1812-15, while the eight watercolours date from 1814. In her catalogue Mildred Archer (1969: 317-23) dated the watercolours to 1833 through confusing his work with that of another Robert Smith (1792-1882), a Captain in the British regiment of the line H.M. 44th (East Essex) Foot, which was in India 1825-33. This Captain Smith prepared an illustrated diary of Indian views from 1828-33 and drew various panoramas of Indian cities, all now in the Victoria and Albert Museum (Rohatgi and Parlett: 207-10).

Our Robert Smith joined the Bengal Engineers immediately after his arrival in Calcutta in 1805. His first post was as Assistant to Major Fleming in building at the Nawab's palace at Murshidabad a new Palladian banqueting hall for entertaining British visitors, a building which he was subsequently to paint.

Robert Smith, The Nawab’s Palace at Murshidabad, 1814. Watercolour on paper. 19 by 35 cm. WD2094.

After completing a number of engineering works in Bengal in 1808-10, Smith went off on the Governor-General Lord Minto's expedition to capture Mauritius from the French in 1810. On his return he was commended by the Surveyor General as ‘by far the best draughtsman I am acquainted with’, which may be one of the reasons he was selected to accompany as A.D.C. the Commander-in-Chief Sir George Nugent on his tour of the Upper Provinces, 1812-13. We learn more of his artistic talents from his art-loving admirer Lady Nugent in her Journal : ‘Received a present of drawings from Mr. Smith, an engineer A.D.C. He draws beautifully, and his sketches are all so correct, that I know every place immediately’ (v. I, 277).

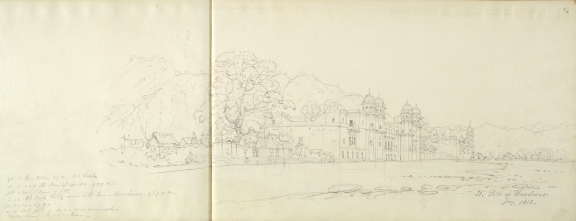

Robert Smith, The Ghats at Haridwar, January 1813. Pencil on paper. Size of folio: 27 by 44.5 cm. WD309, ff.21v, 22.

WD309 covers Smith’s time with the Nugents December 1812 to January 1813 when they were travelling from Haryana up to Haridwar. On a later occasion Lady Nugent wrote: ‘I took the engineer officer, Mr. Smith, with me, and we projected a drawing of the line of march, which will be a treasure to me if he executes it according to my plan, and I have little doubt of its being quite perfect, by what I have seen of his drawings’ (v. I, 395).

Robert Smith, Sketches on the Line of March, 1814. Pencil on paper. 27 by 44.5 cm. WD312, f.25v.

Of the many images in these five sketchbooks, I have selected two, one indicative of Smith’s remarkable draughtsmanship, the other illustrating Lady Nugent’s comments about her proposed line of march (although this drawing is actually from a later tour with Lord Moira, not with the Nugents).

He was next appointed as Inspecting Engineer to accompany Lord Moira (both Governor-General and Commander-in-Chief) on his tour to the Upper Provinces from May 1814, being ‘selected from his character for talents and abilities’. He was with Moira until the end of 1814 when he joined General Martindell's Division in the Anglo-Nepal War of 1814-15, when he was appointed Assistant Field Engineer.

Archer conflates the two Robert Smiths (1969: 317-18) and when discussing the eight fine watercolours by Robert Smith in the collection (ibid., 322-3), gives them the precise dates in 1833 when the other Robert Smith visited these places according to his journal in the V & A, forgetting that our Robert Smith had gone to England in 1830 and retired in 1832. Giles Tillotson (in Bayly 1990: no. 258), aware of this inconvenient fact, but still following Archer's precise datings, gives them to this second Robert Smith, with whose work they have nothing in common. In fact the entire group is earlier, some of them being painted on paper watermarked 1807. They form a series of views along the river Ganges, from Murshidabad to Allahabad, and can best be dated to Smith's journey upriver to join Lord Moira in 1814.

Robert Smith, Distant View of the Ganges at Bhagalpur, with Augustus Cleveland’s House, 1814. Watercolour on paper, 19 by 35 cm. WD2092.

Robert Smith, Aurangzeb’s Mosque at Varanasi, 1814. Watercolour on paper, 19 by 35 cm. WD2089.

Robert Smith, Mosque and Fort at Allahabad, 1814. Watercolour on paper, 19 by 35 cm. WD2087.

Not only are these superb watercolours, they give us precious information about the past before the age of photography. Smith’s view of Allahabad, for instance, focuses on a strange looking hybrid of a building, which is referred to by Lord Moira in his journal entry for 27 September 1814: ‘A mosque of rather elegant structure stands on the esplanade beyond the glacis. When we obtained possession of Allahabad, the proprietary right in the mosque was considered as transferred by the former Government to ours; and from some temporary exigency, the building was filled with stores. These being subsequently removed, much injury, through wantonness or neglect, was suffered by the edifice; and upon some crude suggestion, our Government had directed it to be pulled down. ... The Moslems now implored that the building might be regarded as a monument of piety, and be spared. I have ordered that it shall be cleansed and repaired, and then delivered over to the petitioners’ (Hastings 1858: v. I, 161-2). Smith’s drawing shows us the mosque in question, but it is obvious that after the British got hold of Allahabad in 1801, they ‘classicised’ the mosque as they did the fort’s great gateway and the buildings within, with alterations to the dome and windows.

Thomas Daniell, Fort and Mosque at Allahabad from the River Jumna, 1789. Pencil and wash. 23 by 38 cm. WD196.

A drawing by Thomas Daniell dating from 1789 shows what the original structure looked like complete with cupolas and minarets and pointed Mughal arches on the model of Akbar’s mosque at Fatehpur Sikri. This mosque does not seem to have survived.

An alternative dating for Smith’s series of watercolours is 1822, when he was on his way to take up his post in Delhi (see below), but this seems unlikely in view of the watermarked date. One of the views, of the palace of the Nawab of Murshidabad seen above, is demonstrably the old palace with Major Fleming’s banqueting hall, not the new one built 1829-37 by Colonel McLeod.

William Prinsep, The New Palace at Murshidabad, c. 1835. Watercolour on paper. 22.5 by 44cm. WD4032. The palace was built between 1829 and 1837, but Prinsep’s misplacing of the pediments suggests it was not yet complete when he sketched it.

Smith was next appointed as Superintending Engineer and Executive Officer at Prince of Wales Island (Penang), where he remained until 1819, when he took three years of leave (Smith 1821). He returned to India on 30 October 1822 and was appointed Garrison Engineer and Executive Officer at Delhi, where he remained for the rest of his Indian career, except for joining Lord Combermere's forces for the siege of Bharatpur in 1825-6. There he was wounded – ‘I fear that I shall be sometime deprived of the very efficient services of Captain Smith of the Engineers who has unfortunately received a severe contusion on the left shoulder from a spent shot from a jingal’ (Lord Combermere's Dispatch 26 December 1825). In addition to the usual garrison work in Delhi, Smith repaired the Jami’ Masjid ‘in an entirely satisfactory manner and at an expense considerably below the calculated charges. The fullest testimony borne to his exertions, skill, and economy’ (Revenue Letter from Bengal, 16 August 1827). His most famous enterprise in Delhi was the repair of the upper two storeys of the Qutb Minar, and his controversial addition of a cupola in a Mughal style.

Anon. Delhi artist, The Qutb Minar with Robert Smith’s cupola, c. 1830. Page 28 by 22 cm. Add.Or.4034.

‘Government sanctioned the expense of a small estimate for the care of the Minar under the judicious rules framed by him’ (Political Letter, 9 October 1830, para. 40). ‘The zeal and ability with which he successfully conducted the important public undertaking [the maintenance of the Doab Canal] so long carried on under his superintendence was acknowledged by Government (Misc. Revenue Letter from Bengal, 6 September 1831, para 39).

Smith’s later work in India consists of topographical views in oils and is relatively well known (see Head 1981, Tillotson 1992). Leave to Europe via Bombay was granted in November 1830, when he was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel, and he reported his arrival in England to the Court of Directors on 29 June 1831. His appointment as C.B. was announced in G.O. 3 May 1832. He formally retired in November 1832 at the relatively young age of 45. He continued to paint and numerous of his oil paintings have passed through the salerooms over the years.

Further Reading:

Bengal Army Service Records, IOR: L/MIL/10/21, 131-3, and no. 32

Archer, Mildred, British Drawings in the India Office Library (London, 1969): 317-23

Bayly, C.A. (ed.), The Raj: India and the British 1600-1947 (London, 1991): 257-9

Hastings, 1st Marquess of, The Private Journal of the Marquess of Hastings, K.G., ed. by the Marchioness of Bute (London, 1858)

Head, Raymond, ‘Colonel Robert Smith: Artist., Architect and Engineer’, Country Life 169 (1981): 1432-4, 1524-8

Nugent, Maria, A Journal from the Year 1811 till the Year 1815 … (London, 1839)

Rohatgi, Pauline, and Parlett, Graham, Indian Life and Landscape by Western Artists: Paintings and Drawings from the Victoria and Albert Museum (London and Mumbai, 2008): 207-10

Smith, Robert, Views of Prince of Wales Island, engraved and coloured by William Daniell …(London, 1821)

Tillotson, G., Robert Smith (1787-1873), Paintings of the Mosque at the Qutb Minar, Delhi, Indar Pasricha Fine Arts (London, 1992)

J.P. Losty, Curator of Visual Arts (retired)