The British Library is delighted to have loaned a number of important historical documents to the excellent Mary, Queen of Scots exhibition at National Museums Scotland in Edinburgh. Our loans are displayed alongside jewellery, textiles, furniture, paintings, maps and manuscripts, all of which are used to re-examine the life and legacy of Scotland’s most famous Queen.

On 16 May 1568, Mary fled to England after being forced to abdicate the Scottish throne in favour of her one-year-old son, the future James I of England. As Elizabeth I’s cousin, Mary fully expected to be invited to court, but her Catholic faith and claim to the English throne made her a natural focus for discontented Catholics who refused to conform to Elizabeth's Protestant faith. For reasons of security, therefore, Mary was placed under house arrest and for the next nineteen years would be moved with her household from one secure location to another.

Sketch of Tutbury Castle, Staffordshire: London, British Library, MS Additional 33594, f. 174

One of the British Library loans currently on display in Edinburgh is this sketch of Tutbury Castle, Staffordshire, in which Mary was first imprisoned in 1569 and again in 1584. Mary complained that ‘I am in a walled enclosure, on the top of a hill exposed to the winds and inclemencies of heaven’, and that her own apartments were ‘two little miserable rooms, so excessively cold, especially at night’. The castle bridge and gate-house are visible bottom-right and on the left the Queen’s presence chamber and bedchamber have been identified along with rooms for her gentlewomen of the chamber, surgeon, ‘poticary’ and her secretary, Claude Nau.

Sketch of the trial of Mary, Queen of Scots: London, British Library, MS Additional 48027, f. 569*

In 1586, Mary was brought to trial for complicity in the Babington plot. The hearing took place on 14–15 October 1586 in the Great Chamber at Fotheringhay Castle, Northamptonshire, and is illustrated in this pen-and-ink sketch from the papers of Robert Beale, Clerk of the Privy Council. Mary is shown twice: aided by two gentlewomen as she enters the court room (top-right), and sitting in a high-backed chair (upper-right, marked ‘A’). Elizabeth did not attend the trial and therefore her chair of state on the dais is empty (top-centre). The trial commissioners are identified by numbers. Elizabeth’s chief advisor, Sir William Cecil, Lord Burghley, shown seated opposite Mary, is ‘2’, and Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth’s principal secretary, shown opposite the vacant chair of state, is ‘28’. The commission of thirty-six peers, privy councillors and judges found Mary guilty of plotting to assassinate Elizabeth.

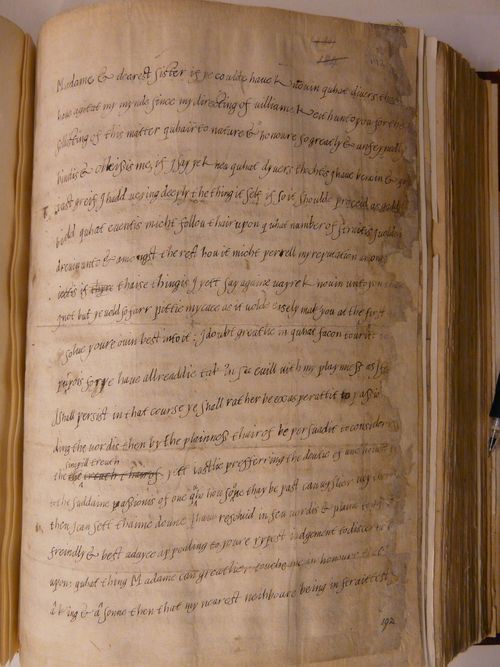

Letter from James VI to Elizabeth I, 26, January 1587: London, British Library, MS Cotton Caligula C IX, f. 192

On 26 January 1587, in a final attempt to save the life of the mother he barely knew, James VI of Scotland wrote to his ‘dearest sister’, Elizabeth I. Beginning two lines from the bottom of this page he asks, ‘Quhat thing, Madame, can greatlier touche me in honoure that is a king and a sonne than that my nearest neihboure, being in straittest [friend]shipp with me, shall rigouruslie putt to death a free souveraigne prince and my natural mother, alyke in estaite and sexe to hir that so uses her … to a harder fortune, and touching hir nearlie in proximitie of bloode?’

Sketch of the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots: London, British Library, MS Additional 48027, f. 650*

Although Elizabeth signed Mary’s death warrant on 1 February 1587, she remained extremely reluctant to execute an anointed sovereign and instructed her secretary, William Davison, not to send it. Lord Burghley, however, acted quickly and had the death warrant carried to Fotheringhay by Robert Beale, who read it aloud to Mary on 7 February, the evening before her execution. This drawing shows Mary three times: entering the hall; being attended by her gentlewomen on the scaffold; and, finally, lying at the block with the executioner's axe raised ready to strike. The Earls of Shrewsbury and Kent are seated to the left (1 & 2) and Sir Amias Paulet, one of Mary’s guards, is seated behind the scaffold (3).

Letter from James VI to Elizabeth I, March 1587: London, British Library, MS Additional 23240, f. 65

When Elizabeth found out that Mary had been executed, she was furious and wrote to James VI apologising for ‘that miserable accident’ and protesting her innocence. This is James’s unsigned draft reply to Elizabeth, dated March 1587, in which he assures her that given ‘youre many & solemne attestationis of youre innocentie I darr not wronge you so farre as not to judge honorablie of youre unspotted pairt thairin …’ Then, seizing the opportunity to press his case to be named as Elizabeth’s heir, he added ‘I looke that ye will geve me at this tyme suche a full satisfaction in all respectis as sall be a meane to strenthin & unite this yle, establishe & maintaine the trew religion’.

The Mary, Queen of Scots exhibition is on at National Museums Scotland until 17 November 2013.