Our recent blog post An Old World View of the New got us thinking about other sources of New World images from within our medieval collections. One excellent example, currently on exhibition in Australia (more below), can be found in Harley MS 2772, which we’ve recently fully-digitised and uploaded to our Digitised Manuscripts site. This manuscript is a collection of fragments of Latin texts, including Macrobius’ Commentary on Cicero's Somnium Scipionis (The Dream of Scipio). Included in the commentary on the ocean is one of the earliest maps ever produced. It is a round diagram of the earth showing the known and unknown lands and oceans, including Italy and the Caspian Sea.

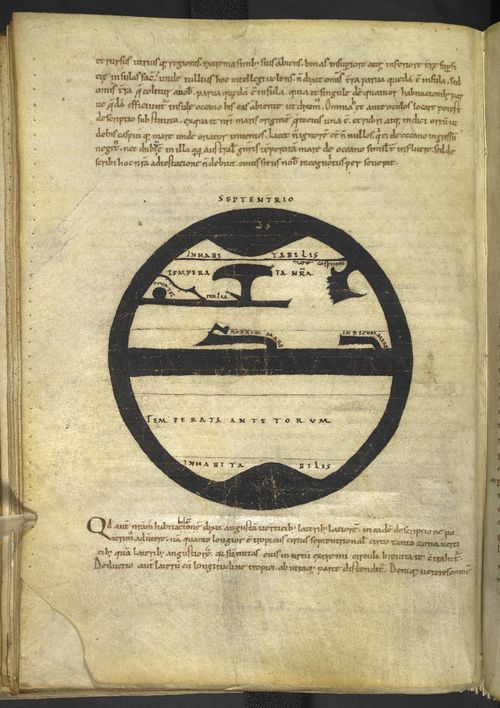

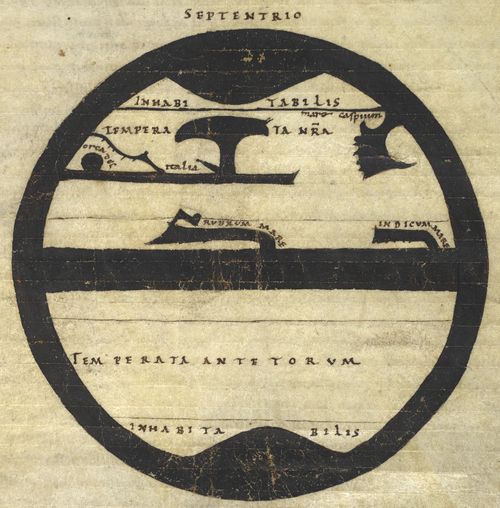

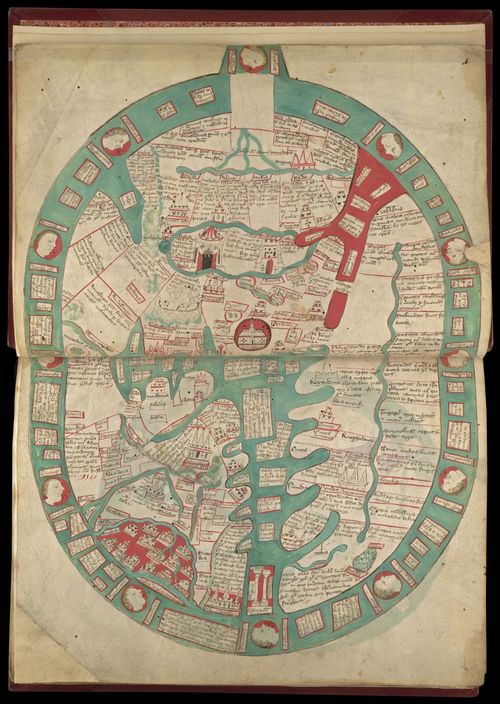

Diagram of the earth and oceans, Harley MS 2772, Germany 11th century, f. 70v

Although this is an eleventh-century copy, the map was first created in the early 5th century, when Macrobius originally wrote his commentary. Most of the maps made at this time focused on the known world of the Roman Empire, but Macrobius was interested in the idea that other parts of the earth might be inhabited. Starting with a commentary on Cicero’s work, in which Scipio views the earth from the heavens in a dream, he writes at length on the nature of the planet and its peoples. He argues against the biblical world-view that Noah’s three sons populated Asia, Europe and Africa, and that, as he had no other son, the remainder of the earth must be uninhabited.

Detail of a diagram of the earth and oceans, Harley MS 2772, Germany 11th century, f. 70v

This diagram divides the earth into five zones, the extreme north and south which are labelled ‘INHABITABILIS’ (uninhabitable), the torrid zone at the Equator with its boiling hot sea, ‘RUBRUM MARE’ (red sea) and in between the two temperate zones. The one in the north is ‘TEMPERATA NOSTRA’ (our temperate zone), with Italy at the centre and bordered by the Caspian Sea and the Orkney Islands (‘ORCADES’). To the south is ‘TEMPERATA ANTETORUM’, which probably means something like ‘outside temperate zone’, i.e. outside the known world an area which is not designated as unpopulated.

So could this be the earliest map of the antipodes? The Australians certainly think so! A current exhibition in The National Library of Australia in Canberra entitled Mapping our World: Terra Incognita to Australia features this manuscript from the British Library.

Other medieval maps on loan for the exhibition are:

The Anglo-Saxon World Map, one of the earliest surviving maps from Western Europe, which shows nothing further south than Ethiopia, and after that there are only monsters.

Anglo-Saxon world map, England (Canterbury) 2nd quarter of the 11th century, Cotton MS Tiberius B V, f. 56v

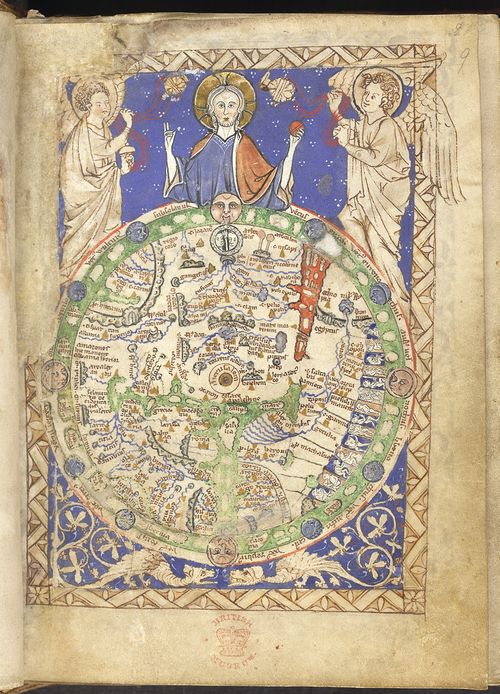

The Psalter World Map, a very small but detailed depiction of the earth with Jerusalem at the centre in a book containing a collection of psalms and prayers, made in south-east England in the mid-13th century. As this is a religious work, God and the angels preside over the earth.

Psalter World Map, England, c. 1265, Additional MS 28681, f. 9r

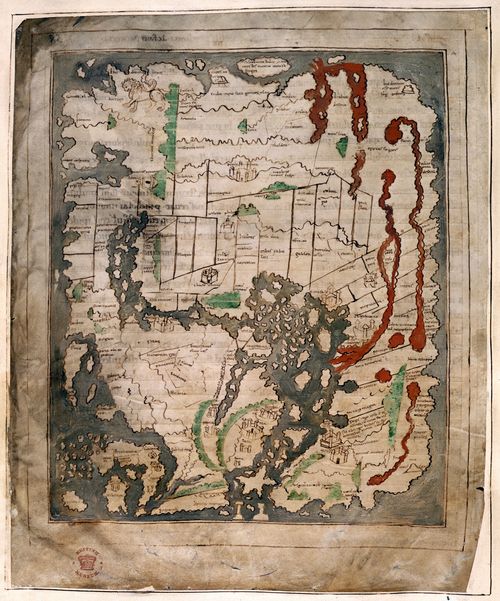

And finally, the map from Higden’s Polychronicon (or universal history) from Ramsay Abbey focuses on England (in red), but contains details of provinces and towns in Europe, Asia and Africa.

Map of the World from the Polychronicon, England, c. 1350, Royal MS 14 C IX, ff. 1v-2

Of course, Australia does not appear on any of the above, and it is not until the 16th century that an unknown southern continent ‘Terra Australis’ or perhaps even the ‘Londe of Java’, as depicted in Henry VIII’s Boke of Idrography can be found.

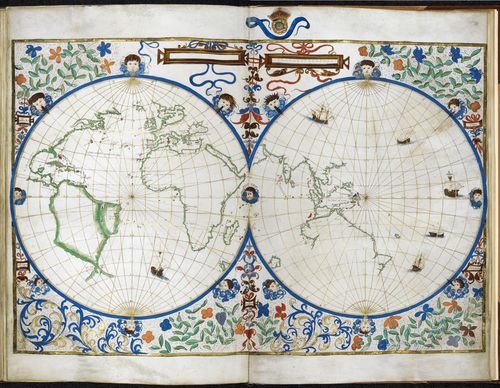

Jean Rotz, Map of the Two Hemispheres, France and England, 1542, Royal 20 E IX, ff. 29v-30

The exhibition catalogue contains these and many more gorgeous reproductions of maps of the world and Australia, including coastal maps and diagrams by the early settlers. Please have a look at Mapping our World: Terra Incognita to Australia (Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2013), and as always, you can follow us on Twitter @BLMedieval.

- Chantry Westwell