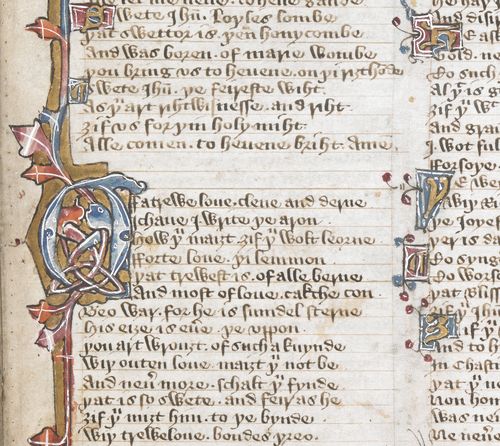

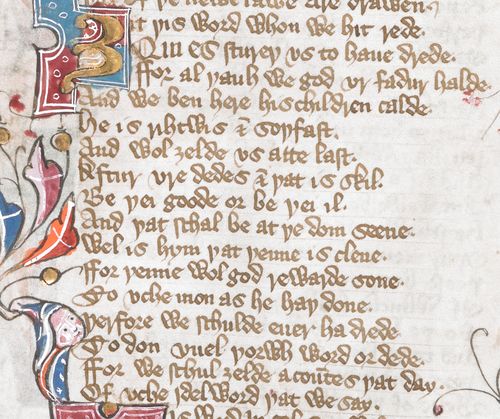

It’s like putting a face to a well-known name for the first time. Often mentioned in scholarship on late medieval English books, but rarely reproduced, the Simeon manuscript is online at last on Digitised Manuscripts. So what are the first impressions now that Add MS 22283 is available for close-up digital scrutiny? Bling. Conspicuous, ostentatious display of gold-leaf on virtually all of its massive pages. Think of exquisite books of hours such as British Library, Egerton MS 1151, and then imagine the complete opposite. Although it too is comprised of texts for pious readers, Simeon is no personal devotional pocket book, intricately decorated to draw in the eye of the reader, but a huge tome measuring some 590 x 390 mm whose open pages would have glittered from afar across the medieval hall, chapel, or library. Folio 90r is typical: illuminated initials mark the start of each verse stanza, and even paragraph marks are decorated with gold:

The beginning of ‘Of a true love clean and derne’, the Love Rune by Thomas of Hales, Add MS 22283, f. 90r

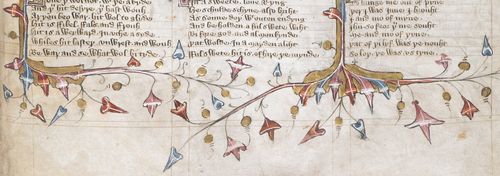

At the bottom of this page two full-length bar borders terminate in elaborate gold-leaf extensions that form the ground for huge, freeform sprays in the generous lower margin:

Sprays on gold-leaf grounds, Add MS 22283, f. 90r

When one has ceased to be dazzled, however, closer inspection – so much more convenient with the digital format than when consulting the massive volume itself -- reveals many interesting and curious details. At least one of the artists indulged in expressive exuberance in the interiors and extensions of initials. A fine example occurs on folio 4v, where a naturalistic – though blue -- dog curls inside a T, the descending stroke of the letter curving up and round like a leash attached to the dog’s collar. If one imagines the image turned through 90 degrees, the dog sniffs the letter like a hound following a scent:

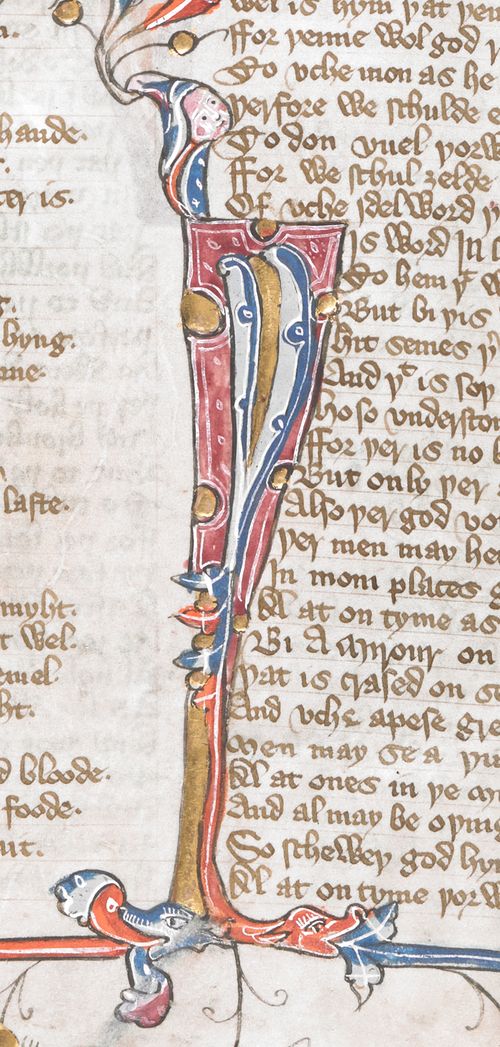

I

nitial T marking the beginning of the homily of the gospel for the second Sunday after Trinity in the Northern Homily Cycle, Add MS 22283, f. 4v

Possibly there were originally more zoomorphic initials by this witty and observant artist in the 176 or so folios that have been lost at the beginning of the manuscript. Initials later in the volume display animal forms of rather more whimsical, less fully-realised character, for example the reptilian creature that materialises from the foliage in the initial A on folio 149r:

Initial A marking the second part of The Form of Living by Richard Rolle, Add MS 22283, f. 149r

On fol. 21r the serif of a T extends to suggest an elongated creature with an protruding snout:

Initial T marking the beginning of the homily on the gospel for the feast of St Thomas in the Northern Homily Cycle, Add MS 22283, fol. 21r

On folio 33v two animal heads (dogs again?) spew out sprays at the base of a letter thorn (th):

Initial thorn marking a new section in the Speculum Vitae, Add MS 22283, f. 33v

But the extension at the top of this letter is even more interesting, for here a human face looks pensively at the text:

Human face protruding from an initial, Add MS 22283, f. 33v

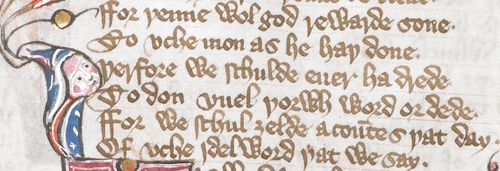

The face serves as a particularly effective nota bene, its expression of concern suggesting the appropriate response from the reader, or from even the artist himself, to the dreadful warning in the text it contemplates:

Passage from the Speculum Vitae, Add MS 22283, f. 33v

The passage is from the Speculum Vitae, a Middle English commentary on the Pater Noster prayer; here the author comments on the phrase qui es (who art [in heaven]), stating that it should stir dread of punishment at the Last Judgement. In the original Middle English the passage reads:

Ȝit þis word whon we hit rede

Qui es stureþ vs to haue drede.

For al þauh we god vr fader halde

And we ben here his children calde

He is rihtwis and soþfast

And wol ȝelde vs atte last

Aftur vre dedes and þat is skil

Be þei goode or be þei il.

And þat schal be at þe dom seene

Wel is hym þat þenne is clene

For þenne wol god rewarde sone

To vche mon as he haþ done.

Þerfore we schulde euer ha drede

To don vuel þorwh word or dede.

For we schul ȝelde acountes þat day

Of vche idel word þat we say.

(‘Yet when we read this phrase qui es, it stirs dread in us. For although we consider God our father and are called his children, he is righteous and truthful and will pay us back for our deeds at the end, according to whether they are good or bad, as makes sense. And that shall be seen at the Last Judgement; it will be well for anyone then who is clean of sin. For then God will reward each person according to his deeds. Therefore we should always dread doing evil by word or deed. For we shall be called to account that day for each idle word that we have said.’)

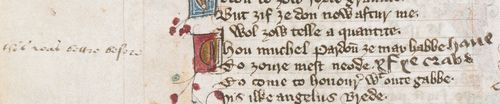

Other details discovered by close examination are the traces left by early readers of Simeon, readers that pre-date by a long way the only known owner, John Simeon, who sold the manuscript to the British Library in 1858. One early reader updates the original Middle English ‘ȝe [ye] may habbe /To ȝoure mest neode [to your most need]’, writing ‘haue yf [if] ye crave’ in a coarse hand. A later reader remarks sardonically, ‘this read bettre before’ (folio 2v):

Early readers’ responses to the Northern Homily Cycle, Add MS 22283, f. 2v

One gets a sense of a community of readers through the ages, engaging in different ways with the challenges of the Middle English and with each other.

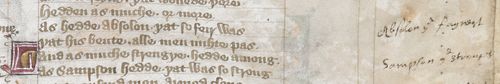

Annotations in Latin suggest that some early readers of Simeon had received at least a grammar-school education (and were therefore probably male). One Latin-writing annotator identifies the author of a text as the famous fourteenth-century mystic Walter Hilton in a side-note, ‘tractatus Magistri Walteri de Hilton’ (folio 151v). This one-off identification suggests that Hilton was of particular interest to this reader. Another annotator notes the subject of an exemplum, writing ‘of a kene swerd’ (of a keen sword) in a one-off rubric (folio 86v). Another picks out the names and attributes of certain characters in the Prick of Conscience (folio 77r), for example ‘Absolon the fairest’ and ‘Sampson the strongest’:

A reader’s response to the Prick of Conscience, Add MS 22283, f. 77r

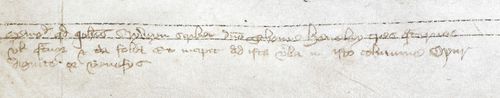

A note in the lower margin of folio 38r takes us from the world of readers of the manuscript to that of the scribes who produced books such as these, or used them as exemplars. This note refers to a certain John Scryveyn and Thomas Heneley and their involvement in book copying:

Note concerning a copying commission by Thomas Heneley for John Scryveyn, Add MS 22283, f. 38r

H. E. Allen noted long ago (Times Literary Supplement, 8 February 1936, p. 116) that this note relates to another note of similar wording in the famous Vernon manuscript (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Eng. poet. a. 1). The link between the two notes is one of several pieces of evidence that Simeon was made in association with Vernon. Another link between Simeon and Vernon is the fact that the main scribe of both books is the same. The Vernon-Simeon scribe, as we might call him, uses spellings and forms associated with the dialects of the West Midlands and has a careful, unshowy round hand typified by the backwards curl at the bottom of the letter thorn and the relative heights of the ascenders in w (see þat and was in the second line of the image from folio 77r, above). Evidence like this points intriguingly to the little-understood world of scribal activity and the making and decoration of books in England around 1400 of which the Simeon manuscript is a product. It is to be hoped that the digitisation of Simeon will help to uncover more of this lost world and shed light on its mysteries.

The Simeon Manuscript Project team at the University of Birmingham, who have collaborated with the British Library in the digitisation of the Simeon manuscript, is studying some of these problems. We would be delighted to hear from anyone who thinks they have identified any of the Simeon scribal hands in another manuscript or document or has found comparable decoration. For information about the research and related projects and to contact the team please visit the project website www.birmingham.ac.uk/simeonmanuscript and of course please upload your comments to this blog. We will be posting further guest entries about our work on the British Library’s Medieval Manuscripts blog as the project develops.

- Wendy Scase, University of Birmingham